If you want to understand why The Beatles eventually stopped playing live and retreated to a basement in London to record Sgt. Pepper, you have to look at the sheer, unadulterated chaos of 1963 to 1966. Honestly, it wasn't just music. It was a riot. Ron Howard’s documentary The Beatles Eight Days a Week The Touring Years captures this better than almost any other piece of media because it focuses on the one thing we often forget: they were actually a really tight live band before the screaming got too loud.

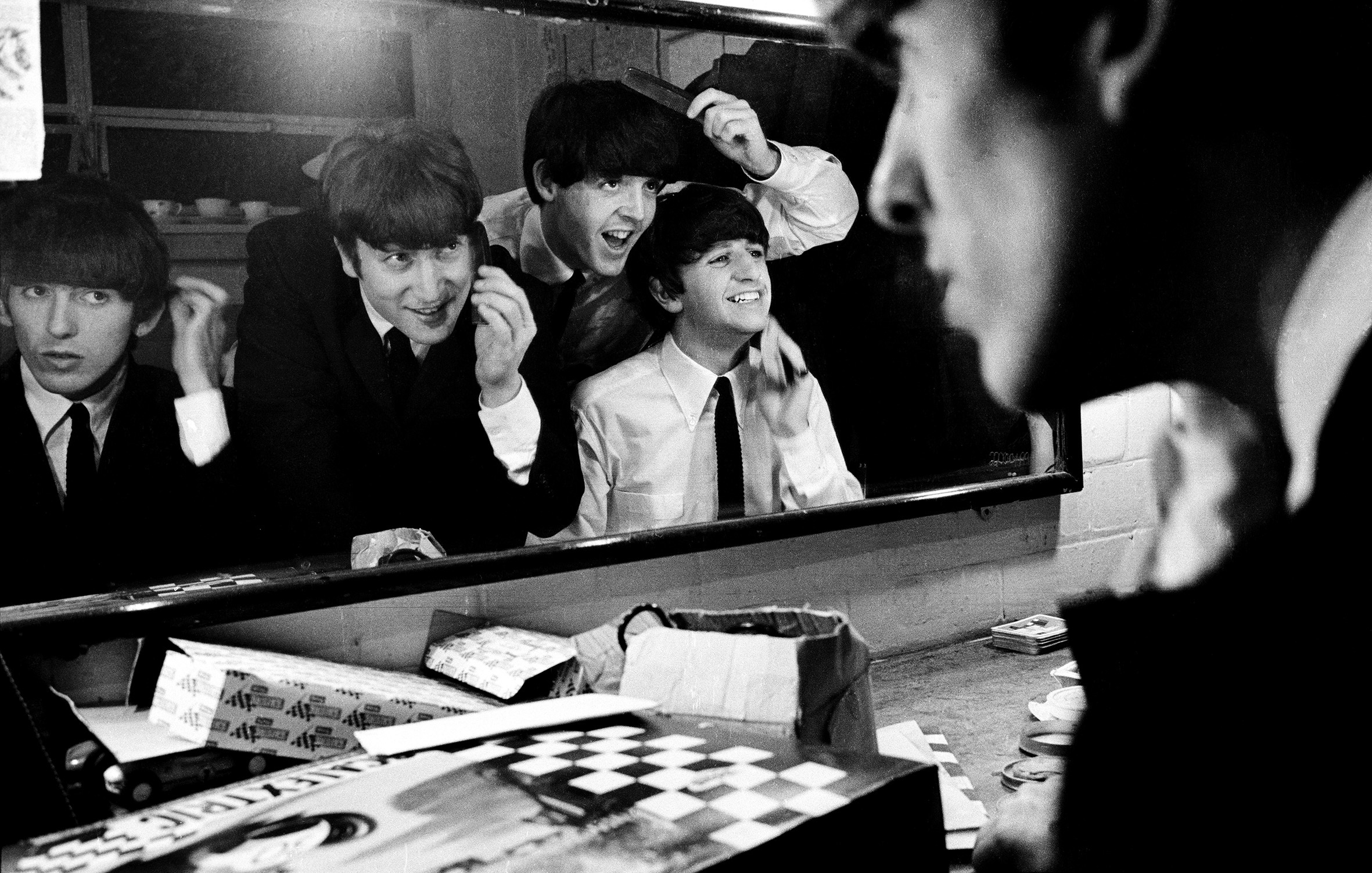

People think they know the story. Four guys from Liverpool play the Cavern, go to Hamburg, hit the Ed Sullivan Show, and the world explodes. But the documentary shows the grit. It shows the sweat. It shows the moment John, Paul, George, and Ringo realized that nobody was actually listening to the songs anymore.

The Sound of 17,000 Screaming Kids

Imagine trying to play a concert where you can't hear your own guitar. That was the reality. In The Beatles Eight Days a Week The Touring Years, the restored footage from Shea Stadium in 1965 is terrifying. It’s 55,000 people. The "PA system" was basically the stadium’s announcement speakers—the kind used to tell people where the hot dog stand is. Ringo Starr has famously said he had to watch the sway of his bandmates' backsides just to know where they were in the beat. He couldn't hear the drums. He couldn't hear the bass.

It was a sonic mess.

Yet, they were still incredible. The film highlights how their apprenticeship in Hamburg, playing eight hours a night in dive bars, turned them into a machine. They were punchy. They were loud. They were funny. But as the venues got bigger, the intimacy died. You see it in their faces as the years progress in the film. The joy of 1963 turns into the thousand-yard stare of 1966.

✨ Don't miss: Carrie Bradshaw apt NYC: Why Fans Still Flock to Perry Street

The Decision That Changed Music History

The documentary spends a lot of time on the 1966 tour, which was, frankly, a disaster. They were bigger than Jesus (according to John's misinterpreted quote), they were being threatened by the Marcos regime in the Philippines, and the KKK was burning their records in the American South.

By the time they hit Candlestick Park in San Francisco on August 29, 1966, they were done.

Paul McCartney knew it was the end. He asked their press officer, Tony Barrow, to record the show on a cassette recorder. If you listen to that audio—or watch the segments in the film—you hear a band that is exhausted. They didn't even play any songs from Revolver, which they had just released. Why? Because the music they were writing in the studio had become too complex for a stage where they couldn't even hear a C-major chord.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Documentary

Some critics argue that the film glosses over the darker parts of the Beatles' personal lives. That’s missing the point. Howard wasn't trying to write a tell-all biography. He was trying to document the phenomenon of the performance.

🔗 Read more: Brother May I Have Some Oats Script: Why This Bizarre Pig Meme Refuses to Die

One of the most powerful segments involves their refusal to play to a segregated audience at the Gator Bowl in Jacksonville, Florida, in 1964. They literally had it written into their contract. They wouldn't play unless the crowd was integrated. It’s a moment of moral clarity that often gets buried under the "mop-top" narrative. They weren't just icons; they were humans with a backbone.

The Technical Magic of the Restoration

The audio work by Giles Martin (son of the legendary George Martin) is the secret sauce here. He took those muddy, distorted recordings and cleaned them up using modern technology. For the first time, you can actually hear the vocal harmonies over the screaming.

It changes how you view them.

You realize they weren't just a boy band. They were a rock and roll powerhouse that was being suffocated by its own fame. The Beatles Eight Days a Week The Touring Years lets you hear the precision of George Harrison’s lead lines and the melodic driving force of Paul’s bass, which was often lost in the transistor radios of the sixties.

💡 You might also like: Brokeback Mountain Gay Scene: What Most People Get Wrong

The Shift to the Studio

When the touring stopped, the art began. But the film argues—rightly so—that the studio years wouldn't have happened without the pressure cooker of the touring years. They had to be a "four-headed monster" to survive the road. That bond is what allowed them to go into Abbey Road and reinvent what a "record" could be.

If they had stayed on the road, they likely would have broken up by 1967. The road was killing them. George Harrison famously said, "I'm not a Beatle anymore" after that final show. He meant he was no longer a product. He was a musician again.

Actionable Ways to Experience This History

If you really want to dive into this era after watching the film, don't just stick to the "1" hits. You need to hear the progression.

- Listen to Live at the Hollywood Bowl: This is the companion album to the film. It's the best evidence of how good they actually were live. The energy on "Dizzy Miss Lizzy" is pure punk rock.

- Watch the Shea Stadium concert in full: If you can find the restored 30-minute cut that played in theaters with the doc, do it. The scale of it is haunting.

- Compare 'Rubber Soul' to 'Revolver': These two albums were recorded during the height of the touring madness. You can hear the band trying to escape the "three-minute pop song" formula because they knew they didn't have to play them live anymore.

- Check out the 'Get Back' series: Once you finish Eight Days a Week, go watch Peter Jackson’s Get Back. It shows the band three years after they stopped touring, trying to find that "live" magic again in a cold rehearsal space. It completes the circle.

The legacy of the touring years isn't the records sold or the records broken. It's the fact that four guys managed to stay sane (mostly) while the entire world tried to tear a piece of them away. Ron Howard’s film is the definitive look at that claustrophobic, exhilarating, and ultimately unsustainable life on the move.