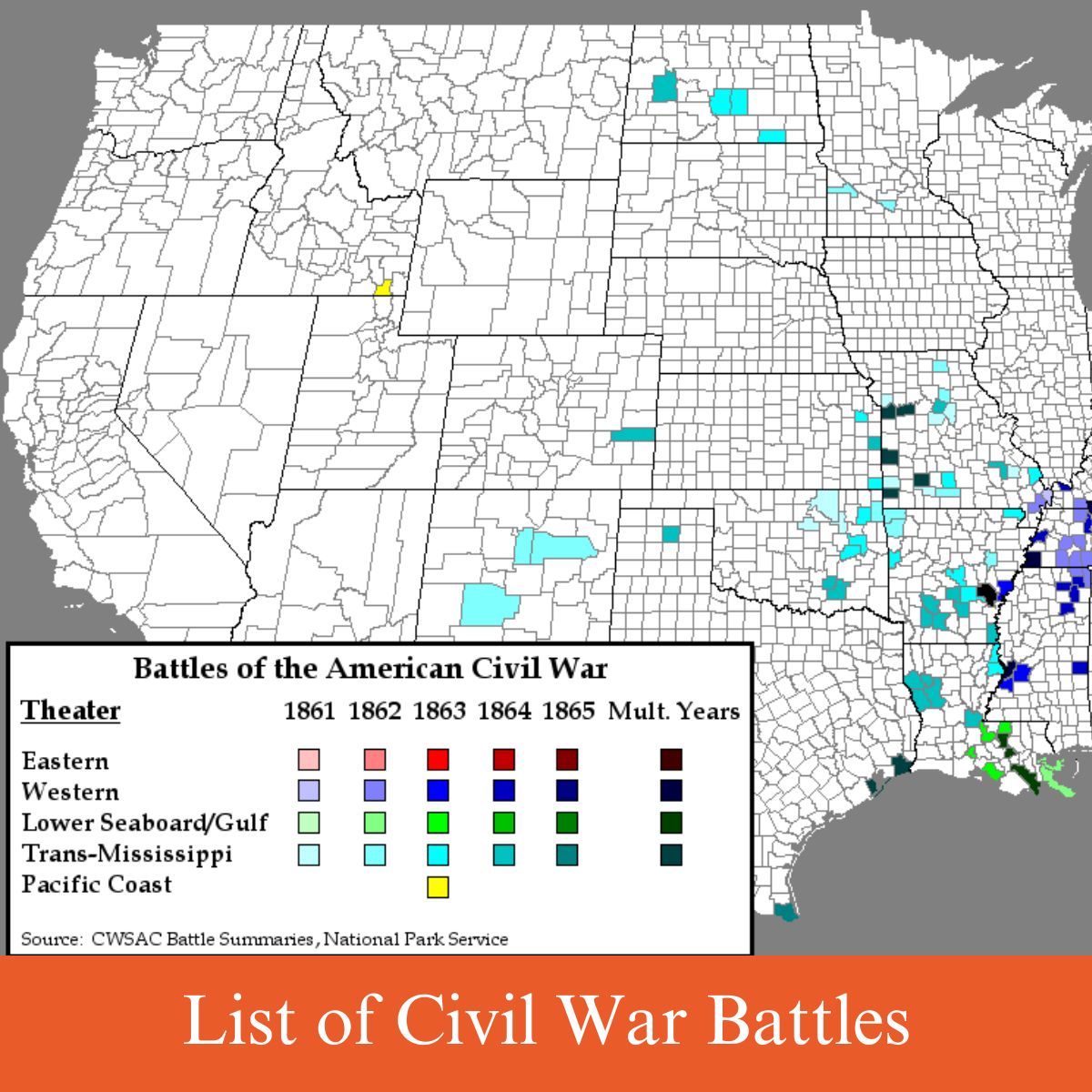

You look at a battles of civil war map and you probably see a bunch of red and blue dots scattered across the Eastern Seaboard and the deep South. It looks clean. It looks organized. But honestly? It's a mess. Most of those maps you find in textbooks or on quick Google searches give you the "Greatest Hits"—Gettysburg, Antietam, Shiloh—and then they just sort of ignore the thousands of skirmishes that actually defined the war for the people living through it.

If you really want to understand the conflict, you have to look past the big icons. The war wasn't just a handful of set-piece battles. It was a four-year-long grinding gears of movement that covered over 10,000 locations.

Most people don't realize that the geography of the war was dictated by things as boring as railroad gauges and the depth of river mud. You can't just draw a line from Point A to Point B. Logistics mattered more than "valor" or whatever other romanticized word we use today.

The Eastern Theater: Not Just a Straight Line to Richmond

Everybody focuses on Virginia. It makes sense, right? The two capitals, Washington D.C. and Richmond, were barely 100 miles apart. If you look at a battles of civil war map centered on the East, it looks like a deadly game of ping-pong.

The terrain here was a nightmare. You had the Blue Ridge Mountains to the west and a series of rivers—the Rappahannock, the Rapidan, the James—running west to east. These weren't just scenery; they were massive defensive walls. Robert E. Lee was a master at using this "folded" landscape to hide his movements. When you see those big swooping arrows on a map representing the 1862 Peninsula Campaign, remember that those arrows represent men wading through waist-deep swamps and dying of malaria before they ever saw a Confederate uniform.

George B. McClellan, the Union General, was basically terrified of moving too fast. He saw the map and saw obstacles everywhere. Meanwhile, "Stonewall" Jackson was treating the Shenandoah Valley like his personal racetrack. The Valley was the "breadbasket" of the Confederacy, and its north-south orientation meant it was a backdoor into the North. If you follow the tracks on a detailed map, you'll see why the Union couldn't just "march on Richmond." They were constantly getting distracted by Rebels popping up in their backyard.

It's weird to think about, but the fighting in the East was incredibly claustrophobic. Battles like The Wilderness (1864) happened in such thick underbrush that soldiers couldn't see twenty feet in front of them. The map says "battlefield," but the reality was a localized hellscape where the woods literally caught fire.

The Western Theater is Where the War Was Actually Won

If you talk to serious historians like James McPherson or Shelby Foote, they'll tell you: forget Virginia for a second. The Western Theater is where the Union broke the South's back.

💡 You might also like: January 14, 2026: Why This Wednesday Actually Matters More Than You Think

This is where the battles of civil war map gets massive. We're talking about thousands of miles of territory from the Appalachians to the Mississippi River. While the Army of the Potomac was stumbling around Virginia, Ulysses S. Grant was out west figuring out that the key to the whole thing was the water.

Rivers were the highways of the 1860s.

Look at the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers. By taking Fort Henry and Fort Donelson, Grant didn't just win a "battle." He opened a door. He used the navy—those weird, lumbering ironclad "brown-water" ships—to bypass Confederate land defenses. Suddenly, the Union was deep in Tennessee.

Then you have Vicksburg. Look at a map of the Mississippi River's bends. Vicksburg sits on a high bluff at a hairpin turn. It was a natural fortress. Grant's campaign to take it wasn't a single fight; it was a months-long masterclass in engineering, canal-digging, and eventually, a brutal siege. When Vicksburg fell on July 4, 1863 (one day after Gettysburg ended), the Confederacy was literally cut in half. No more cattle from Texas. No more grain from Arkansas.

It was over, even if it took two more years for the folks in Richmond to realize it.

The "Trans-Mississippi" and the Forgotten Fronts

One of the biggest issues with your average battles of civil war map is that it stops at the Mississippi River. That’s a mistake. There was a whole lot of chaos happening in Missouri, Arkansas, and even out in the New Mexico Territory.

The Battle of Glorieta Pass? It happened in New Mexico. People call it the "Gettysburg of the West." The Confederates wanted the gold mines in Colorado and the ports in California. If they had succeeded, the map of the United States would look fundamentally different today. But you rarely see that on a standard map because it doesn't fit the "North vs. South" linear narrative.

📖 Related: Black Red Wing Shoes: Why the Heritage Flex Still Wins in 2026

Missouri was even worse. It wasn't just armies fighting; it was neighbors murdering each other. Guerrilla warfare was the norm. Men like William Quantrill and "Bloody Bill" Anderson led raids that were basically just organized massacres. On a map, these show up as tiny dots or maybe aren't listed at all, but for the civilian population, this was the "real" war.

Logistics: The Lines Between the Dots

What really makes a battles of civil war map come alive isn't the Crossed Swords icons. It's the thin black lines representing the railroads.

The North had about 22,000 miles of track. The South had maybe 9,000, and much of it was different "gauges," meaning the tracks were different widths. You couldn't just run a train from one end of the South to the other. You'd have to stop, unload everything, move it across town, and reload it onto a different train.

Think about that.

During the Chattanooga campaign, the Union moved 20,000 troops over 1,200 miles by rail in just over a week. It was a logistical miracle for the time. The South couldn't match that. When you look at a map and see Union armies suddenly appearing in places they shouldn't be, it’s usually because of the rails.

How to Actually Use a Civil War Map for Research

If you're trying to dig into this for a project or just because you're a history nerd, don't rely on a single image. You need layers.

First, find a map that shows topography. If you don't see the hills and the swamps, the troop movements make no sense. Why did Lee wait at Marye's Heights in Fredericksburg? Because it was a hill with a stone wall at the bottom. It was a kill zone. A flat map won't show you why the Union lost 12,000 men there in a single afternoon.

👉 See also: Finding the Right Word That Starts With AJ for Games and Everyday Writing

Second, look at "Order of Battle" maps. These show where specific regiments were at specific times of the day. They're messy and hard to read, but they show the chaos of command.

Lastly, check out the American Battlefield Trust. They have some of the most accurate, GPS-mapped layouts of these sites. They actually go out and survey the land to make sure the "dots" on the map are where the blood was actually spilled.

Realities of the "Total War" Mapping

By 1864, the map changed again. Sherman’s March to the Sea wasn't about capturing a specific city for its own sake. It was about destroying the map itself.

Sherman cut his supply lines. He didn't care about the railroad dots anymore—he was busy tearing the rails up, heating them over bonfires, and twisting them around trees (they called them "Sherman's Neckties"). When you look at a map of his path from Atlanta to Savannah, it's a wide "scar" about 60 miles across. This was psychological warfare. He wanted to make the South feel the "hard hand of war," and his path on the map proves he did exactly that.

Actionable Steps for Deepening Your Understanding

To truly grasp the geography of the Civil War, stop looking at static images and start engaging with the terrain.

- Use the Library of Congress Digital Collections: They have the actual hand-drawn maps used by generals like Jedediah Hotchkiss (Lee’s mapmaker). Seeing the coffee stains and the pencil marks makes the history feel a lot more real.

- Overlay Historical Maps with Google Earth: Take a 1863 map of a place like Vicksburg or Gettysburg and overlay it on a modern satellite view. You'll see how much the suburbs have eaten the battlefields, but you'll also see why certain ridges were held at all costs.

- Focus on One Campaign at a Time: Don't try to memorize the whole war. Pick the Vicksburg Campaign or the 1864 Overland Campaign. Trace the movements day by day.

- Visit the "Small" Parks: Everyone goes to Gettysburg. Try going to a place like Pea Ridge in Arkansas or Stones River in Tennessee. The maps there are often more intimate and easier to wrap your head around because the scale is smaller.

The map is just a tool. The real story is in the mud, the rivers, and the rail lines that forced these men to fight in specific, terrible places. Understanding the battles of civil war map isn't about memorizing dates; it's about seeing the physical constraints that shaped the destiny of the country.