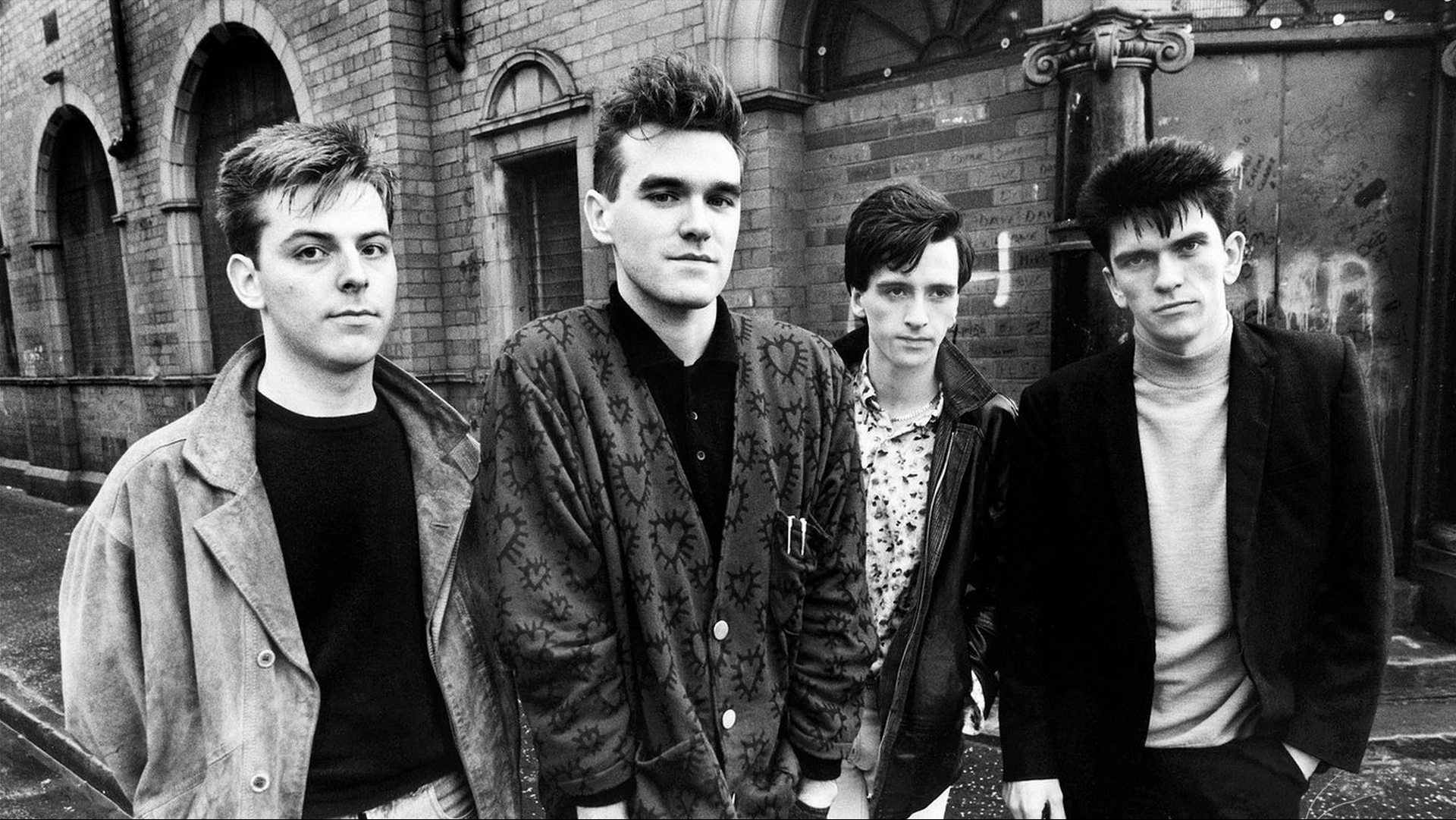

They were never supposed to work. Honestly, looking back at the four band members of The Smiths in 1982, the math just doesn't add up. You had a shy, bookish vegan who obsessed over 1960s kitchen-sink dramas. You had a teenage guitar prodigy who looked like he stepped off a mod scooter. Then there was a rhythm section that, frankly, didn't seem to belong in the same room as the other two. But for five years, they were the only thing that mattered in British music.

It’s easy to focus on Morrissey. Everyone does. His voice is the one that launched a thousand moping teenagers into poetry books. But the dynamic of the band members of The Smiths was far more fragile and complex than just "a singer and his backing band." It was a volatile chemistry experiment that eventually blew up the lab.

The Architect: Johnny Marr

If Morrissey was the soul, Johnny Marr was the engine. Without Marr, there is no band. Period. He was barely nineteen when he knocked on Steven Patrick Morrissey's door in Stretford. He wasn't looking for a friend; he was looking for a lyricist who could match his ambition. Marr’s guitar style—jangle-pop, heavily layered, influenced by African highlife and James Burton—became the blueprint for indie rock for the next forty years.

He didn't play solos. He played textures.

Marr used a Rickenbacker 330 and a Fender Twin Reverb to create a sound that was somehow thin and massive at the same time. Think about "This Charming Man." That opening riff isn't a melody; it’s a declaration of war against the synth-heavy pop of the early 80s. Marr was the musical director, the guy who stayed up late in the studio while the others slept, layering track upon track of acoustic and electric guitars to create that "wall of jangle."

✨ Don't miss: Do You Believe in Love: The Song That Almost Ended Huey Lewis and the News

The Voice and the Villain: Morrissey

Morrissey is a complicated figure now, but in 1984, he was a revelation. He gave a voice to the marginalized, the celibate, and the terminally awkward. He famously replaced the typical rock-and-roll bravado with gladioli in his back pocket and a hearing aid worn as a fashion statement. His lyrics were dense with references to Oscar Wilde, Shelagh Delaney, and Elizabeth Smart.

People forget how funny he was. Songs like "Frankly, Mr. Shankly" or "Some Girls Are Bigger Than Others" show a wit that was often missed by critics who just saw him as "miserable." But the tension between Morrissey’s rigid personal vision and the reality of being in a band started the cracks. He hated the music industry. He hated the "game." That attitude made them legends, but it also made them impossible to manage.

The Engine Room: Andy Rourke and Mike Joyce

This is where the story gets messy. Andy Rourke and Mike Joyce are often sidelined in the history of the band members of The Smiths, which is a total injustice. Rourke’s bass playing was incredibly melodic. If you listen to "Barbarism Begins at Home," you’re hearing a funk influence that Morrissey probably wouldn't have admitted to liking. Rourke and Marr were childhood friends, and that telepathy is what held the songs together when Morrissey’s vocals went off on a tangent.

Mike Joyce provided the muscle. He came from a punk background. He hit the drums hard, providing a necessary grit that kept the band from becoming too "precious."

However, the internal hierarchy was skewed. Morrissey and Marr were the directors; Rourke and Joyce were the employees. This distinction led to the infamous 1990s High Court battle over royalties, where a judge famously described Morrissey as "devious, truculent and unreliable" when he wasn't prepared to share the wealth equally. It was a sad, litigious end for a group that supposedly stood for "the common people."

The Short, Violent Life of the Band

They only lasted five years. Four studio albums. That’s it.

The breakup in 1987 wasn't over one big thing; it was a thousand small cuts. Marr was exhausted. He was acting as the band's manager, producer, and primary composer. Morrissey’s obsession with 60s pop covers—like "Work Is a Four-Letter Word"—reportedly drove Marr to the brink. When Marr took a break, a misinterpreted NME headline suggested he had quit. Instead of fixing it, the communication broke down entirely.

The band members of The Smiths never reunited. Not for Coachella, not for a billion dollars, not even to celebrate their induction into any halls of fame. Marr went on to play with everyone from The The to Modest Mouse and Hans Zimmer. Morrissey went solo and eventually became a polarizing political figure. Rourke and Joyce were left with the fallout of the court cases.

💡 You might also like: Diego Klattenhoff Movies and TV Shows: Why He’s the Best Actor You Keep Forgetting You Know

Why They Still Matter in 2026

You can't walk into a record store today without seeing a Smiths shirt. Their influence is everywhere, from the "sad boy" aesthetics of modern indie to the intricate guitar work of bands like The 1975 or Radiohead. They proved that you could be literate, weird, and incredibly popular all at once. They didn't need synthesizers or big hair. They just needed a guitar, a bass, drums, and a lot of feelings.

Honestly, the tragedy of the band members of The Smiths is that they were too perfect for their own good. The friction that made the music great was the same friction that burned the house down.

What to Do Next

If you’re just getting into the band or want to understand the musicianship better, stop listening to the "Greatest Hits" for a second. Do this instead:

- Listen to "The Queen Is Dead" on high-quality headphones. Pay attention specifically to Andy Rourke’s bassline. It’s the lead instrument for half the song.

- Read "Set the Boy Free" by Johnny Marr. It’s the most level-headed account of how the band actually functioned on a day-to-day basis.

- Watch the 1984 Rockpalast performance. It shows the raw energy of the four members before the fame and the lawyers got involved. You’ll see a band that actually looked like they liked each other.

- Analyze the "Meat Is Murder" era production. This was the point where Marr really started experimenting with effects, moving away from the simple jangle of the debut album.

The Smiths weren't just a band; they were a moment in time that can't be recreated. Understanding the individual contributions of the four band members of The Smiths is the only way to truly appreciate why that music still sounds so vital today.