Suzanne Collins didn't have to go this hard. When she announced she was returning to Panem, everyone sort of assumed we’d get a fun, breezy prequel about a young, misunderstood Haymitch or maybe the First Rebellion. Instead, we got The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes book, a dense, psychological character study of a teenage sociopath. It’s a lot.

The book is basically a 500-page descent into the mind of Coriolanus Snow. If you’ve only seen the movie, you’re honestly missing about sixty percent of the actual story. The film is a visual spectacle, sure, but the book is a claustrophobic nightmare. It forces you to live inside the head of a guy who views every single human interaction as a tactical move on a chessboard. He's not a hero. He's barely even an anti-hero. He’s a narcissist who is desperately trying to stay relevant in a post-war society that has outgrown his family's prestige.

The internal monologue you didn't get on screen

Movies struggle with internal thoughts. It’s just the nature of the medium. In the film version of The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes, Tom Blyth does a fantastic job with his facial expressions, but you can't truly see the rot. In the book? It’s everywhere.

Every time Coriolanus does something "kind" for Lucy Gray Baird, the prose immediately reveals his selfish motive. He doesn't give her food because he's worried she’s starving; he gives her food because a starving tribute is a losing tribute, and a losing tribute makes him look like a failure. It’s deeply unsettling. This isn't a "star-crossed lovers" situation. It’s a "possessive captor and a survivalist performer" dynamic.

Collins uses a limited third-person perspective that feels almost like a fever dream. You start to see Panem through his warped lens. To Coryo—as his cousin Tigris calls him—the world is divided into predators and prey. If you aren't the one holding the whip, you're the one getting lashed. There is no middle ground. This binary worldview is what eventually turns him into the cold-blooded president we meet in the original trilogy.

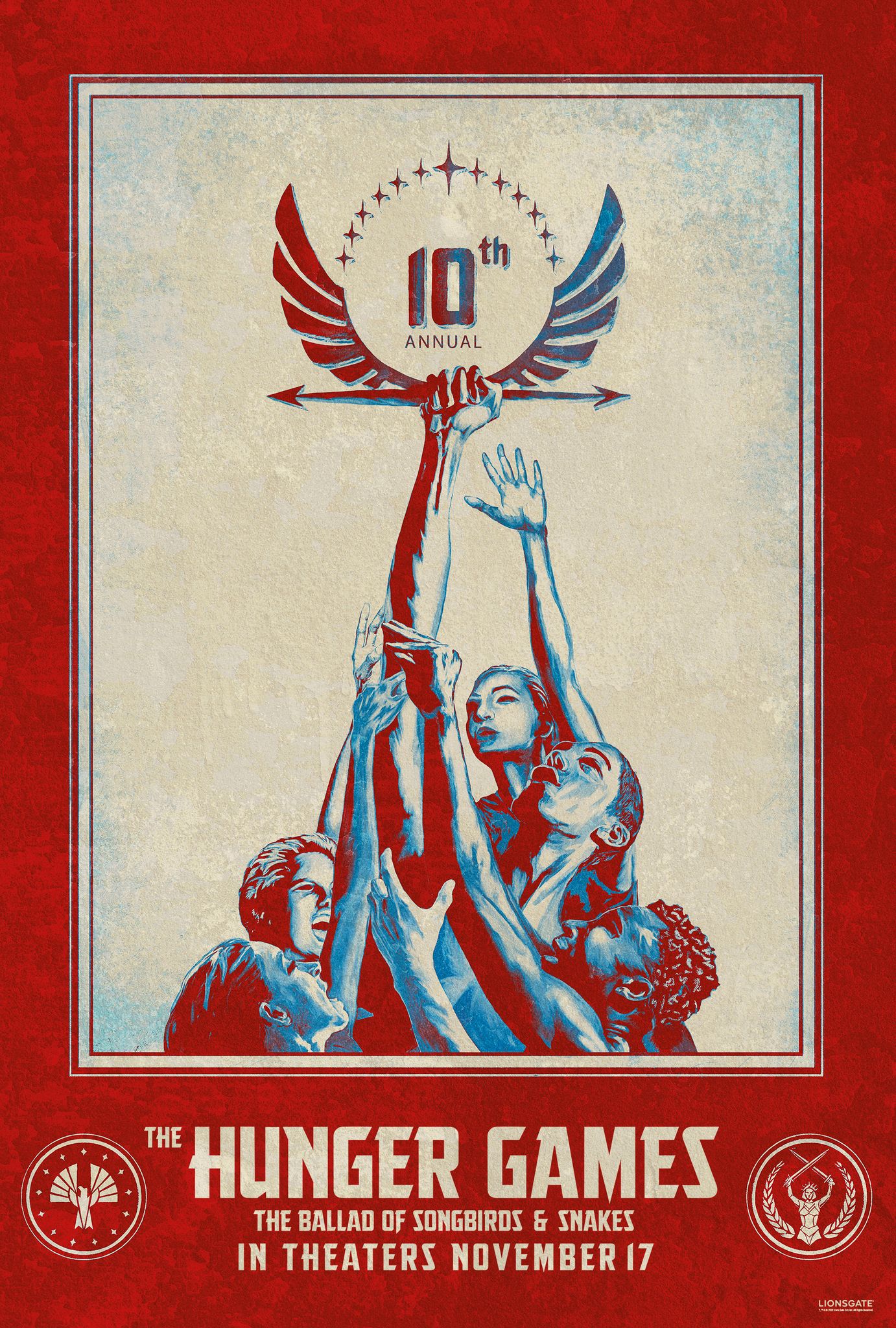

Why the 10th Hunger Games felt so much worse

The Games in this book are janky. They’re held in a crumbling sports arena that’s been bombed out during the war. There are no high-tech force fields or fancy CGI "mutts" yet. It’s just kids in a pit with whatever weapons they can find.

Honestly, the "low-tech" nature of the 10th Games makes them significantly more gruesome than the 74th Games Katniss participated in. In the original trilogy, the Games were a polished media event. In The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes, they’re a disorganized slaughter. Tributes die of starvation before the Games even begin. They die of infections. They die because a stray beam falls on them.

✨ Don't miss: Why ASAP Rocky F kin Problems Still Runs the Club Over a Decade Later

The Capitol citizens don't even want to watch. This is the big hurdle Snow has to overcome. He’s the one who helps Dr. Gaul—the terrifying Head Gamemaker—realize that for the Games to work, people have to be invested. They need to bet on them. They need to feel like they’re part of the spectacle.

Snow didn't just win the Games; he invented the modern version of them. He’s the reason people have to watch their children die on live television.

The Dr. Gaul and Casca Highbottom factor

We need to talk about Dr. Volumnia Gaul. She is the true villain of the story, even if Snow is the protagonist. She’s a mad scientist who views the world as a giant lab experiment. Viola Davis played her with a theatrical flair, but in the book, she is even more clinical and terrifying. She challenges Snow to define what human beings are when you strip away the "civilization" of the Capitol. Her answer? We are monsters.

Then there’s Dean Casca Highbottom.

The book treats him with a lot more nuance. He’s a man drowning in regret because he’s the one who technically "invented" the idea of the Hunger Games as a drunken joke during university. He never intended for it to become a reality. He hates Snow not just because of Coriolanus’s father, but because he sees the same budding evil in the son. Highbottom’s drug addiction to morphling isn't just a character quirk; it’s a desperate attempt to numb the guilt of creating a literal death cult.

District 12 and the "Peacekeeper" detour

The third act of the book is where a lot of people get tripped up. It shifts gears entirely. Coriolanus is sent to District 12 to serve as a Peacekeeper, and the story slows down significantly.

🔗 Read more: Ashley My 600 Pound Life Now: What Really Happened to the Show’s Most Memorable Ashleys

While the movie rushes through this part to get to the "big finale," the book lingers on the boredom and the grime. This is where we see the Covey—Lucy Gray’s musical troupe. They aren't "from" District 12 in the traditional sense; they’re nomads who got stuck there when the borders closed. This distinction is huge. It explains why Lucy Gray doesn't fit the mold of a "typical" tribute.

The tension in the woods near the end of the book is palpable. When Snow and Lucy Gray head out into the rain, the atmosphere shifts from a romance to a psychological thriller. You realize that neither of them trusts the other. Lucy Gray is smart—she realizes that Coriolanus killed his "friend" Sejanus Plinth. And Coriolanus realizes that she knows.

The ending is intentionally ambiguous. Did he hit her? Did she survive? The book doesn't give you the satisfaction of an answer because, to Snow, it doesn't matter. Once she’s gone, she’s just a ghost he can bury along with his conscience.

The Sejanus Plinth tragedy

Sejanus is the moral compass of the story, which makes his fate all the more devastating. He’s a Capitol citizen who was born in District 2. He hates the Capitol. He hates the Games. He tries to be a good person in a world that eats good people for breakfast.

Snow views Sejanus as a burden. He "saves" him multiple times, but only because he doesn't want to be associated with Sejanus’s failures. When Snow eventually betrays him—sending a jabberjay recording of Sejanus’s rebel plans to the Capitol—it’s the moment of no return. It’s the definitive proof that Coriolanus Snow has no soul. He trades his friend’s life for a chance at a career. It's cold. It's calculated. It's quintessentially Snow.

Is it worth reading if you've seen the film?

Absolutely. 100%.

💡 You might also like: Album Hopes and Fears: Why We Obsess Over Music That Doesn't Exist Yet

The book provides a level of world-building that the movie simply can't touch. You learn about the "Dark Days" of the rebellion, the origins of the hanging tree song, and the specific political machinations that kept the Capitol in power when they were on the verge of collapse.

It’s also a masterclass in unreliable narration. You have to read between the lines to see what’s actually happening versus how Snow is justifying it to himself.

How to approach the story now

If you're planning to dive into the book (or revisit it), keep these things in mind to get the most out of the experience:

- Watch the songs: Collins wrote the lyrics into the text, but hearing the melodies (many of which were composed for the film) while you read those chapters adds a layer of haunting beauty.

- Focus on the birds: The symbolism of the mockingjays versus the jabberjays is much more prominent in the prose. The jabberjays represent Capitol control; mockingjays represent the "chaos" of nature and rebellion.

- Track the "Coriolanus" name: Look up the Shakespearean play Coriolanus. The parallels between the Roman general and Snow are intentional. Both are men who despise the "common" people and believe in a strict, almost fascistic order.

The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes isn't a story about a good boy gone bad. It’s a story about a bad boy who was given every opportunity to be better and chose power every single time. It’s a bleak, brilliant addition to the Hunger Games lore that reminds us that the real monsters aren't in the arena—they're the ones sitting in the stands, deciding who lives and dies.

To fully grasp the political philosophy behind Panem, compare the different definitions of "The Social Contract" presented by Dr. Gaul and Sejanus. Gaul believes humans need the state to keep them from killing each other, while Sejanus believes the state is the one doing the killing. This debate is the heartbeat of the novel. Read the chapters involving their debates slowly; they explain exactly why the 12-district system exists the way it does decades later.