Alice Cooper didn't just invent shock rock. He perfected the psychological thriller in four minutes and fifty-five seconds. When you sit down and really listen to The Ballad of Dwight Fry, you aren't just hearing a song from the 1971 album Love It to Death. You’re eavesdropping on a mental collapse. It’s raw. It’s jagged. It feels dangerously close to the edge.

Most people think of Alice Cooper and see the makeup, the snakes, and the guillotines. They see the showman. But in the early seventies, the band—and yes, Alice Cooper was a full five-piece band back then—was doing something much more sophisticated than just trying to gross out parents. They were exploring the dark corners of the human psyche. The Ballad of Dwight Fry is the crown jewel of that era. It’s a tribute to Dwight Frye (the "e" was dropped for the song title), the character actor famous for playing Renfield in the 1931 Dracula and Fritz in Frankenstein.

He was the guy who made "crazy" look terrifying on the silver screen. Alice took that cinematic insanity and put it into a rock context. It worked. Maybe a little too well.

The Straightjacket and the Pillows: Recording a Masterpiece

Bob Ezrin. That’s the name you need to know if you want to understand why this track sounds so claustrophobic. Ezrin was the young producer who took a group of hungry, slightly chaotic musicians from Detroit and turned them into a precision tool. He didn't want Alice to just sing about being in a mental institution. He wanted him to be there.

To get that strained, desperate vocal performance in The Ballad of Dwight Fry, Ezrin didn't just tell Alice to "act." He made him live it. Alice actually wore a straightjacket in the studio while recording the vocals. He spent hours crouched on the floor, confined, restricted, and increasingly frustrated. You can hear it in his voice. When he screams about wanting to "get out of here," that isn't some rehearsed theater kid yelling for effect. That’s a man who has been sweating in canvas straps under hot studio lights for a long time.

The production is layered with these tiny, unsettling details. Take the intro. That’s a child’s voice. "When are you coming home, Daddy?" It’s heartbreaking. It grounds the horror in reality. This isn't a monster in a castle; it’s a father who has snapped, leaving a family behind. The contrast between that innocent voice and the creeping, minor-key piano riff is enough to give anyone chills.

Ezrin also had Alice sing through a cage of pillows at one point to muffle the sound, creating an acoustic environment that feels like a padded cell. It’s tactile. It’s uncomfortable. It’s brilliant.

The Narrative Arc of a Breakdown

The song starts slow. It’s almost a lullaby, but a sick one. Alice’s voice is a whisper. He’s telling us about his "man-colored skin" and how he’s been gone for fourteen days. The math of the song is interesting because it moves from a daze into a full-blown manic episode.

"I was looking for a job, but I couldn't find one / My anyway, done I was looking for a job..."

🔗 Read more: A Simple Favor Blake Lively: Why Emily Nelson Is Still the Ultimate Screen Mystery

The lyrics reflect a fragmented mind. He’s trying to explain why he’s in the "sanitarium," but he can’t quite keep his thoughts straight. He mentions his tie being too tight. It’s such a mundane, everyday annoyance that spirals into a symbol of total domestic suffocation. We’ve all felt that, right? That sense that the world is closing in? Cooper just took that feeling and turned the volume up to eleven.

Then the chorus hits. It’s an explosion.

The transition from the verse to the chorus is one of the most effective dynamic shifts in 1970s rock. The band—Glen Buxton, Michael Bruce, Dennis Dunaway, and Neal Smith—plays with a kind of controlled looseness. Dunaway’s bass lines are particularly melodic here, acting as a counterpoint to the screeching guitar work. They aren't just playing a chord progression. They’re building a wall of sound that eventually crashes down on the listener.

Why Dwight Frye?

You might wonder why they picked a character actor from the 30s as the namesake for their masterpiece. Honestly, it’s because Dwight Frye was the original "creep." He was the guy who specialized in the peripheral weirdo. By naming the song after him, Alice Cooper was signaling a deep love for classic horror cinema.

It wasn't about the monsters. It was about the men who became monsters because the world broke them.

Dwight Frye died young, often pigeonholed into roles that required him to giggle maniacally or cower in shadows. There’s a tragedy to his career that mirrors the tragedy of the character in the song. It’s a tribute to the outsiders.

Live Performance: The Birth of the Straightjacket Act

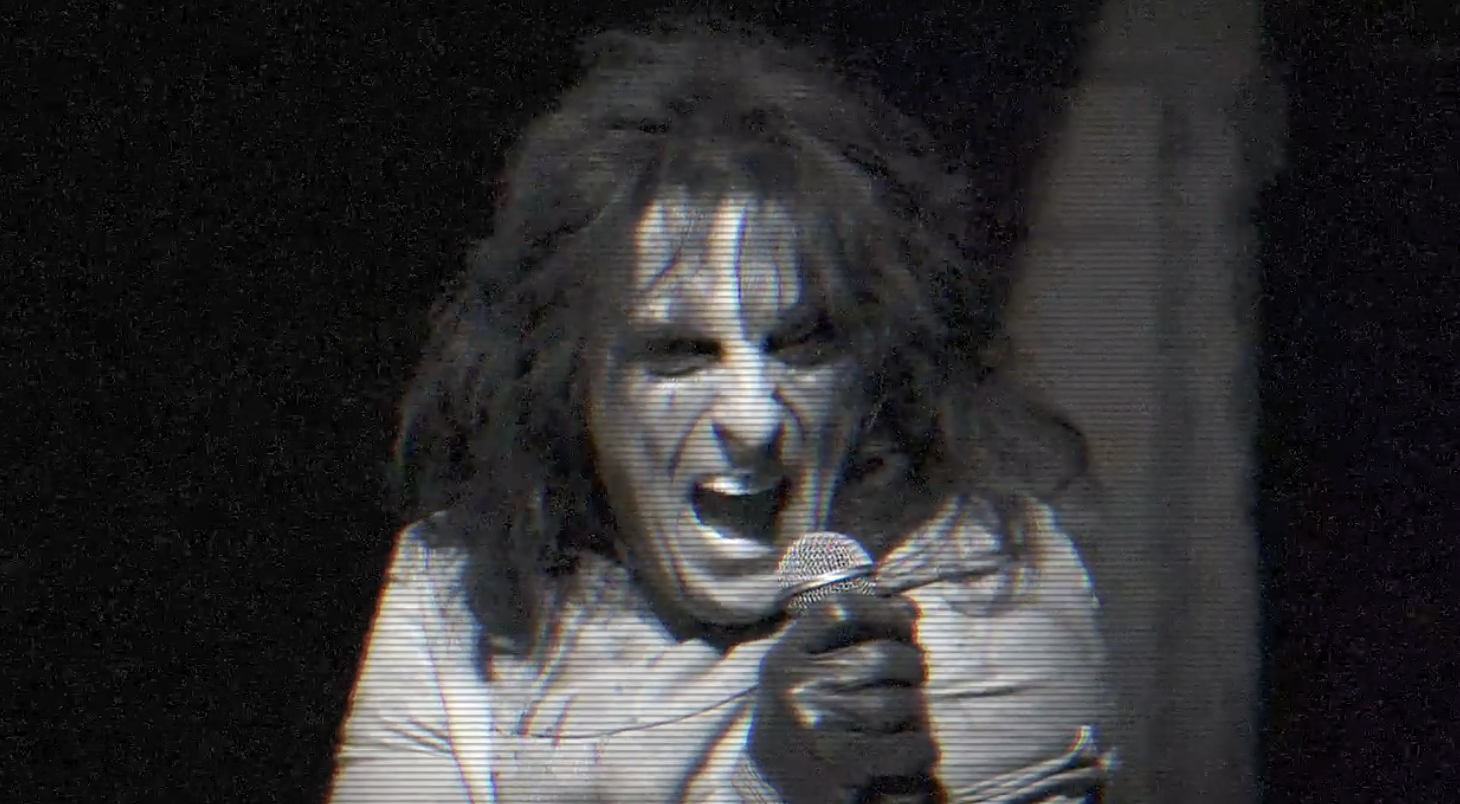

If the recording of The Ballad of Dwight Fry is a psychological horror film, the live performance was a grand guignol theater piece. This is where Alice’s legend was truly forged.

Picture it: 1971. The lights go down. A nurse—often played by the incredible Sheryl Cooper (Alice’s wife)—drags a struggling Alice onto the stage. He’s in the straightjacket. The band begins that haunting piano intro. For the next five minutes, the audience isn't watching a rock concert. They’re watching a public execution of the spirit.

💡 You might also like: The A Wrinkle in Time Cast: Why This Massive Star Power Didn't Save the Movie

Alice would thrash. He would fight the straps. By the time the song reached its climax, he would break free, usually leading into a sequence involving a guillotine or an electric chair. It was high art and low-brow thrills mashed together. No one else was doing this. Not Led Zeppelin. Not Black Sabbath. They were "heavy," sure, but Alice Cooper was unsettling.

The theatricality of The Ballad of Dwight Fry paved the way for everything from David Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust to the elaborate stage shows of Slipknot or Ghost. It proved that you could use a rock stage to tell a narrative story that was as compelling as a movie.

Cultural Impact and the "C" Word

Let’s talk about "Crazy." In the early 70s, mental health wasn't a topic discussed with any nuance. You were either "normal" or you were "insane." The Ballad of Dwight Fry exists in that uncomfortable middle ground. It’s about the process of losing it.

The song has been covered by everyone from The Melvins to Slash. Why? Because it’s a masterclass in tension. It doesn't rely on a catchy pop hook. It relies on atmosphere. It’s a song that shouldn't work on the radio, yet it became a staple of FM rock because it’s simply too powerful to ignore.

Interestingly, some critics at the time didn't get it. They saw it as a gimmick. They missed the empathy. If you listen closely, the song isn't mocking the mentally ill. It’s empathizing with the pressure of a society that demands a job, a tie, and a "normal" life until you literally crack under the weight of it.

Love It to Death, the album featuring this track, was the turning point for the band. It moved them away from the psychedelic meandering of their first two albums (Pretties for You and Easy Action) and into the hard-hitting, theatrical rock that would make them icons. Without "Dwight Fry," there is no "School’s Out." There is no "No More Mr. Nice Guy." This was the proof of concept.

The Technical Brilliance of the Composition

Musically, the song is surprisingly complex. It’s not just a three-chord wonder.

- The Piano Motif: Simple, repetitive, and intentionally "off." It mimics the repetitive thoughts of a spiraling mind.

- The Bass Performance: Dennis Dunaway doesn't just hold down the root note. He plays around the vocal, creating a sense of movement.

- The Dynamics: The song moves from a whisper to a scream (literally). This "soft-loud-soft" dynamic was later popularized by bands like the Pixies and Nirvana, but Alice was doing it in 1971.

The use of found sounds—the wind, the child’s voice, the banging—adds a cinematic quality that was revolutionary for the time. Bob Ezrin brought his classical training to a garage rock band, and the result was something entirely new: "Chamber Rock."

📖 Related: Cuba Gooding Jr OJ: Why the Performance Everyone Hated Was Actually Genius

What Most People Get Wrong

People often think The Ballad of Dwight Fry is about a guy who is just "evil." It’s not. It’s about a guy who is tired.

The lyrics mention he was "looking for a job." He’s a victim of the American Dream gone sour. The horror comes from how relatable that is. We like to think we’re far away from the guy in the straightjacket, but the song suggests we’re only a few bad weeks away from joining him.

Another misconception is that the song is purely a tribute to the actor. While the name is a nod to Frye, the story is original. It’s a synthesis of 1930s horror aesthetics and 1970s social anxiety.

How to Truly Experience the Song Today

If you want to understand why this song still matters, you can’t just play it as background music while you’re doing dishes. It doesn't work that way. You have to give it your full attention.

- Find the 1971 Studio Version: While live versions are great for the spectacle, the studio version on Love It to Death has the most nuanced vocal performance.

- Use Headphones: You need to hear the panning, the whispers, and the way the instruments bleed into each other.

- Read the Lyrics While Listening: Notice how the sentences break down. Notice the repetition.

- Watch the Live 1971 Footage: Search for the Good to See You Again, Alice Cooper concert film. Seeing Alice in the jacket while singing this song explains the "theatrical" label better than any book ever could.

Moving Forward with the Ballad

To appreciate the legacy of The Ballad of Dwight Fry, look at how it changed the expectations of a rock song. It stopped being just about a beat and started being about a protagonist.

If you're a musician, study the way Ezrin uses space. If you're a horror fan, look into the filmography of Dwight Frye to see where the inspiration began. Most importantly, recognize that "shock rock" wasn't just about the shock; it was about the truth hiding behind the makeup.

Alice Cooper proved that you could be the villain and the victim at the same time. That’s a lesson that songwriters are still trying to learn today. Go back and listen to the track again. Pay attention to that final, fading scream. It’s a reminder that sometimes, the most terrifying thing in the world isn't a ghost or a vampire—it's just a man who has finally had enough.