It starts with a chase. One violin leaps out, hitting that jagged, urgent D minor theme, and before you can even catch your breath, the second violin is right on its heels, mimicking every twist and turn like a shadow with a mind of its own. This is the Bach Concerto in D Minor for Two Violins, or as most musicians call it, the "Bach Double." If you’ve ever stepped foot in a Suzuki recital or flipped on a classical radio station during a rainstorm, you’ve heard it. But hearing it and actually getting it are two different things.

Bach wasn't just writing a pretty tune for two fiddles. He was basically inventing a high-stakes conversation where both speakers are equally brilliant, equally stubborn, and occasionally finish each other's sentences. It’s arguably the most famous work for two solo instruments in the history of Western music. Honestly, it’s the musical equivalent of a perfectly choreographed fight scene in a John Wick movie—precise, relentless, and incredibly satisfying.

The Mystery of When This Thing Was Actually Written

We like to imagine Johann Sebastian Bach sitting in a candlelit room in Leipzig around 1730, scribbling furiously while his twenty children ran around. That’s the traditional story. For a long time, scholars like Christoph Wolff—basically the godfather of Bach research—pointed to his time as the director of the Collegium Musicum in Leipzig as the birthplace of the Bach Concerto in D Minor for Two Violins. The Collegium was this gritty, coffee-house ensemble where professional musicians and talented students jammed together at Zimmermann’s Coffee House. You can almost smell the dark roast and the pipe tobacco when you hear the grit of the first movement.

But there’s a catch. Bach was a notorious recycler. He was the king of "upcycling" his own hits. Some musicologists, looking at the stylistic DNA of the piece, argue it actually dates back earlier, to his time in Köthen (1717–1723). In Köthen, Bach had a prince who actually liked music and a world-class orchestra at his disposal. Whether it was born in a royal court or a caffeine-fueled cafe doesn't change the fact that the autograph score we have today dates to around 1730. He eventually even transcribed it for two harpsichords (BWV 1062), transposed down to C minor, but let’s be real: the violins do it better.

The "Double" is cataloged as BWV 1043. That number is just a filing system, but the music is pure adrenaline.

That Second Movement: Why It Makes Everyone Cry

If the first movement is a chase, the second movement—the Largo ma non tanto—is a long, slow walk at sunset. It’s in F major, which feels like a warm blanket after the cold tension of D minor. This is the movement that shows up in movies when the director wants you to feel a "profound sense of longing."

Why does it work so well? It’s the suspension.

📖 Related: Big Brother 27 Morgan: What Really Happened Behind the Scenes

Bach uses a technique where one violin holds a note while the other moves, creating a momentary dissonance that resolves just as the next one begins. It’s a constant state of tension and release. It’s not just "pretty." It’s structurally perfect. When you listen to the legendary 1961 recording of David Oistrakh and Igor Oistrakh (father and son), you can hear that weird, psychic connection required to pull this off. They aren't just playing notes; they are breathing together.

Some people find the middle movement boring because it doesn't have the "fire" of the outer sections. They're wrong. It’s actually the hardest part to play because there is nowhere to hide. Every vibrato choice, every slight swell in volume, is exposed. It is the heart of the Bach Concerto in D Minor for Two Violins, providing the emotional weight that keeps the whole piece from feeling like just a technical exercise.

Counterpoint is Just a Fancy Word for Teamwork

Let’s talk about counterpoint for a second without sounding like a dry textbook. Basically, Bach was obsessed with the idea that every voice should be important. In a lot of later music, you have a melody (the star) and an accompaniment (the backup singers). Bach doesn't do backup singers.

In the Bach Concerto in D Minor for Two Violins, the two soloists are "equal under the law." If Violin I plays a flurry of sixteenth notes, you can bet Violin II is going to do the exact same thing five seconds later. This is "fugal" writing. It creates a texture so dense and rich that it feels like a physical object.

What’s happening in the orchestra?

The backup band (the strings and the continuo) isn't just sitting there. They provide the "motor." That driving, rhythmic pulse is what gives the Baroque era its energy. It never stops. It’s like a heartbeat. If the soloists are the dancers, the orchestra is the floor they’re dancing on. Without that rock-solid foundation, the complex weaving of the two violins would just fall apart into a mess of strings.

The "Double" in Pop Culture and Modern Learning

It’s hard to overstate how much this piece has saturated our world. It’s the "Stairway to Heaven" of the violin world. Every kid who learns via the Suzuki method hits a wall when they get to the Bach Concerto in D Minor for Two Violins in Book 4 or 5. It’s their rite of passage. If you can play the "Bach Double," you aren't a beginner anymore. You’ve officially entered the world of "real" music.

👉 See also: The Lil Wayne Tracklist for Tha Carter 3: What Most People Get Wrong

But it’s also been sampled, covered, and ripped off more times than we can count.

- Django Reinhardt and Stéphane Grappelli turned it into a jazz masterpiece in 1937. Hearing the "Double" played with manouche swing rhythm is a trip. It proves that Bach’s bones are so strong you can drape almost any style over them.

- It appears in movies like Music of the Heart (Meryl Streep playing a violin teacher in East Harlem).

- It’s a staple for buskers. Why? Because two people playing this on a subway platform sounds like a whole orchestra is coming through the tunnel.

Breaking Down the Three Movements

You have to look at the architecture to understand why this piece doesn't get old.

I. Vivace

It’s in 4/4 time, but it feels faster. The opening theme is a "D-minor triad" leap that immediately establishes a sense of gloom and urgency. The two violins enter in imitation. It's aggressive. It's technical. It's the ultimate "check out what I can do" movement.

II. Largo ma non tanto

The time signature shifts to 12/8. It’s a Siciliano—a kind of pastoral dance. This is the movement we talked about earlier. The one that feels like a prayer or a love letter. It’s the longest movement, which is unusual for a concerto of this period, showing that Bach really wanted to dwell in this emotional space.

III. Allegro

We’re back in D minor. It’s fast. It’s triple meter (usually felt in a fast three). The soloists are practically tripping over each other here. The tension builds and builds until the final chord, which, surprisingly, stays in D minor. Usually, Bach likes to end on a "Picardy Third" (turning the final minor chord into a major one to sound happy), but here, he lets the drama stand. He stays in the dark.

Common Misconceptions

People often think the two violin parts are "First" and "Second" in terms of importance. Like, the "better" player takes the first part. That’s total nonsense. In the Bach Concerto in D Minor for Two Violins, the parts are interchangeable. In fact, many professional duos will switch parts halfway through a concert or record it both ways.

✨ Don't miss: Songs by Tyler Childers: What Most People Get Wrong

Another myth is that this is "religious" music. While Bach was deeply religious and signed almost everything Soli Deo Gloria (To God Alone be the Glory), this concerto is secular. it’s instrumental brilliance for the sake of entertainment. It was meant to be enjoyed with a drink in your hand, not necessarily while kneeling in a pew.

How to Listen Like a Pro

If you want to actually appreciate this, don't just put it on as background music while you answer emails.

- Follow one voice: Try to pick out just the second violin and follow it through the whole first movement. It’s hard! Your brain will want to jump to the "lead" melody.

- Listen for the bass: Notice the cello and harpsichord. They are the engine. If they stopped, the whole thing would float away.

- Compare recordings: Listen to a "period instrument" recording (like the Freiburger Barockorchester) where they use gut strings and no vibrato. It sounds raw and earthy. Then listen to a "modern" version like Itzhak Perlman and Isaac Stern. It’s lush, vibrato-heavy, and romantic. Both are "right," but they feel like different pieces of music.

Actionable Next Steps for the Curious

If you’ve made it this far, you’re clearly hooked on the genius of JSB. Here is how to actually integrate this into your life:

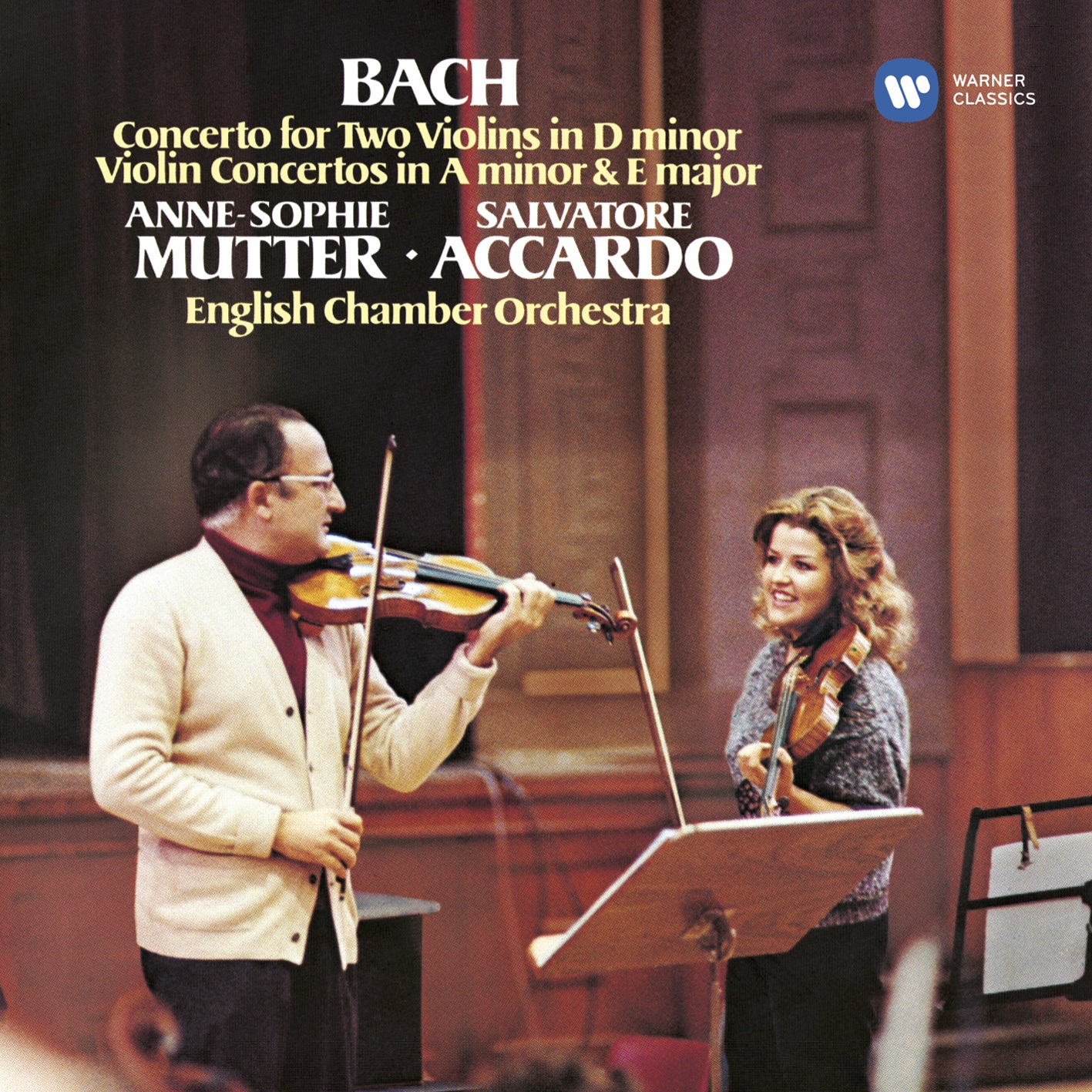

Start with the "Big Three" Recordings

Search for these specific versions to hear the different "flavors" of the concerto:

- The Classic: David and Igor Oistrakh (Royal Philharmonic Orchestra). It’s the gold standard for power and precision.

- The Romantic: Itzhak Perlman and Yehudi Menuhin. It's incredibly expressive and vibrato-heavy.

- The Historically Informed: Rachel Podger and Andrew Manze. They use Baroque bows and period-appropriate techniques. It’s faster and "crunchier."

Watch a Live Performance Visualizer

Go to YouTube and search for "Bach Double Violin Concerto Smalin." You’ll find an animated graphical score. Watching the notes move like colorful bars helps you see the counterpoint. You’ll literally see the two violins chasing each other.

Try the Transcription

If you aren't a fan of the violin (how?), look up the Bach Concerto for Two Harpsichords in C Minor (BWV 1062). It’s the same piece, but the percussive nature of the keyboards gives it a completely different, almost clockwork feel.

Learn the History

Pick up Bach: Music in the Castle of Heaven by John Eliot Gardiner. It’s a long read, but it puts pieces like the D minor concerto into the context of Bach’s chaotic, difficult, and brilliant life. You’ll realize that this "perfect" music was written by a guy who was often underpaid, overworked, and grieving the loss of several children. It makes the music feel a lot more human.

The Bach Concerto in D Minor for Two Violins isn't just a relic from the 1700s. It’s a living blueprint for how two people can disagree, compete, and eventually harmonize perfectly. It’s a reminder that beauty usually comes from tension.