It looked like a lead pipe with wings. Honestly, if you saw the Avro CF 100 Canuck sitting on a tarmac next to a sleek Sabre or a Mig-15, you’d probably think it was a relic from a previous decade. It was chunky. It had those massive, oversized engine nacelles buried right in the wing roots. It didn’t have the swept-back wings that were becoming the "cool" look of the 1950s.

But appearances are deceptive.

While the rest of the world was obsessing over dogfighting agility, Canada had a much bigger problem: a massive, empty, freezing Arctic that looked like a very inviting highway for Soviet bombers. The Avro CF 100 Canuck wasn't built to win a beauty pageant or dance in a turning fight at 20,000 feet. It was built to be a sledgehammer. It was a long-range, all-weather interceptor that could find a target in a blinding blizzard, fly thousands of miles without breaking a sweat, and then unleash enough unguided rockets to turn a formation of Tupolev Tu-4s into confetti.

The "Lead Sled" That Could

The Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) knew they were in a tight spot after World War II. The North was wide open. Radar tech was still pretty primitive. If the Soviets decided to send a fleet of bombers over the North Pole, Canada was the only thing standing between those nukes and North American cities.

Avro Canada stepped up.

They didn't just want to build a plane; they wanted to build the plane. The design process for the Avro CF 100 Canuck started in the late 1940s, led by guys like Edgar Atkin and later John Frost. They needed something twin-engined for reliability (losing an engine over the Yukon is a death sentence) and they needed two seats so a navigator could handle the complex radar while the pilot focused on not crashing into a mountain.

When the prototype, the Mark 1, first flew in 1950 with Bill Waterton at the controls, it was painted jet black. It looked menacing. People started calling it the "Clunk." Some say that was because of the noise the nose gear made when it retracted. Others say it was just because the thing felt solid, heavy, and unbreakable.

Powering the Beast: The Orenda Engine

You can't talk about the Canuck without talking about the Orenda. Early versions actually used Rolls-Royce Avons, but the goal was always Canadian-made power. The Orenda 11 engines were the soul of the Mark 4 and Mark 5 variants. These turbojets provided about 7,300 pounds of thrust each.

That might not sound like much compared to a modern F-22, but for 1954? That was serious muscle.

The Avro CF 100 Canuck became famous for its "short-field" performance. Even though it weighed nearly 35,000 pounds fully loaded, it could get off the ground in a hurry. Pilots loved that. It gave them a sense of security. You’ve got to remember, many of these guys were flying out of remote strips in the middle of nowhere. If you have an engine flame-out on takeoff in a single-engine jet, you’re done. In a "Clunk," you had a fighting chance.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Armament

There is a weird misconception that the Canuck was just another machine-gun fighter. Early marks did carry eight .50 caliber machine guns in a removable ventral pack. That’s a lot of lead. But the real game-changer was the rockets.

The Mark 4 was fitted with wingtip rocket pods.

Inside those pods were 2.75-inch "Mighty Mouse" folding-fin aerial rockets. The idea wasn't to "aim" and "shoot" like a sniper. The idea was to fly toward a bomber stream and saturate the air with 58 rockets per pod. Total chaos. It was a literal wall of explosives. It reflected the brutal reality of Cold War interception: you didn't need to be elegant; you just needed to make sure the bomber didn't reach its target.

The "All-Weather" Myth vs. Reality

People throw around the term "all-weather" like it’s a marketing slogan. For the Avro CF 100 Canuck, it was a survival requirement. The Canadian North is one of the most hostile flying environments on the planet. We’re talking about "black hole" conditions where there are no lights on the ground for hundreds of miles, icing that can seize control surfaces in minutes, and magnetic interference that makes old-school compasses spin like tops.

The CF-100 used the Hughes MG-2 fire-control radar.

👉 See also: Create a Apple Account Online: What Most People Get Wrong

By today’s standards, your microwave has more computing power. But back then, it was cutting-edge. It allowed the crew to intercept targets in total darkness or thick cloud cover. It made the Canuck the only fighter in the world at one point that could effectively guard the northern approaches to the continent.

European pilots were skeptical. Until they saw it in action. During NATO exercises in the 1950s, the Canadians showed up with their big, blunt-nosed jets and consistently "killed" targets that the sleeker British and French fighters couldn't even find in the soup. The Belgian Air Force was so impressed they actually bought 53 of them. It was the only Canadian-designed fighter to be exported in significant numbers until the modern era.

Why It Stayed in Service So Long

The Avro CF 100 Canuck was supposed to be replaced by the legendary (and doomed) Avro Arrow. When the Arrow program was famously scrapped in 1959, the RCAF was left with a massive hole in its defense strategy.

So, they just kept flying the "Clunk."

It stayed in front-line service as an interceptor until 1962, replaced eventually by the CF-101 Voodoo. But that wasn't the end. Not even close. The plane was so stable and had such a huge internal capacity that it was converted into an Electronic Warfare (EW) trainer. These were the "Black Knights" of 414 Squadron. They’d fly around with jamming pods and chaff dispensers, making life miserable for younger pilots in CF-5s and CF-18s during exercises.

The last Canuck didn't retire until 1981.

Think about that. A plane designed in the late 40s was still doing mission-critical work in the age of the Space Shuttle. It was rugged. It was reliable. It was the quintessential Canadian machine—it worked when it was -40 degrees outside and didn't complain.

Comparing the Canuck to its Peers

| Feature | CF-100 Canuck (Mk 5) | Northrop F-89 Scorpion | Gloster Javelin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Role | All-weather Interceptor | All-weather Interceptor | All-weather Interceptor |

| Top Speed | 650 mph | 635 mph | 710 mph |

| Climb Rate | 8,500 ft/min | 7,400 ft/min | 5,400 ft/min |

| Reliability | Exceptionally High | Moderate (Engine issues) | Moderate (Deep stall issues) |

The Javelin was faster, sure. The Scorpion had more sophisticated rockets later on. But the Canuck had the "Goldilocks" zone of range and reliability. It could stay in the air for over three hours. In the vastness of the Canadian Shield, range is the only stat that matters.

The Engineering Quirks You Should Know

It wasn't a perfect airplane. No airplane is. Because the engines were so far apart, if you lost one on takeoff, the "asymmetric thrust" was violent. You had to be fast on the rudder or the plane would cartwheel.

And then there was the "wing drop."

At high altitudes and high Mach numbers, the thick straight wings would start to lose lift unevenly. The plane would suddenly roll to one side. Pilots learned to respect the "buffet." It told you exactly when you were pushing too hard. It was an honest airplane; it didn't hide its flaws behind computer-assisted flight controls because there weren't any. It was all cables, pulleys, and brute strength.

What Happened to the Survivors?

Most of them were scrapped. It’s a bit of a tragedy, honestly. Because the CF-100 was overshadowed by the drama of the Avro Arrow, people forgot just how successful the Canuck actually was. The Arrow was a beautiful failure; the Canuck was a "homely" success.

You can still see them if you know where to look. There’s a beautiful Mark 5 at the Canada Aviation and Space Museum in Ottawa. There’s one sitting on a pedestal in places like North Bay, Ontario—which makes sense, given that North Bay was the heart of Canada’s Cold War air defense.

👉 See also: Apple Music Statistics: Why the Numbers Actually Matter for Your Playlists

Actionable Insights for Aviation Enthusiasts

If you’re looking to truly understand the Avro CF 100 Canuck, don't just look at the stat sheet. You have to look at the context of the era.

- Visit a surviving airframe: If you’re in Ontario or Alberta, seek out the local museums. Seeing the size of the Orenda intake in person explains why this thing was called a "Lead Sled."

- Read the pilot accounts: Look for memoirs by RCAF pilots like Jack Woodman or Bill Waterton. They describe the "Clunk" not as a weapon, but as a stubborn partner that would get you home through a blizzard when nothing else could.

- Study the Electronic Warfare era: The 1960s-80s "Black Knight" phase of the CF-100 is arguably more interesting than its interceptor phase. It shows how a well-built airframe can be adapted for roles the original designers never imagined.

- Compare it to the F-86: Look at how Canada operated both simultaneously. The F-86 was for the "glamour" of Europe; the CF-100 was for the dirty, cold work of protecting the home front.

The Avro CF 100 Canuck remains a testament to a time when Canada was an aviation superpower. It wasn't just a plane; it was a statement that Canada could defend its own sovereign airspace without having to borrow equipment from anyone else. It was loud, it was heavy, and it was exactly what the country needed at the exact moment it needed it.

Key Technical Specifications for the Avro CF 100 Canuck Mk 5:

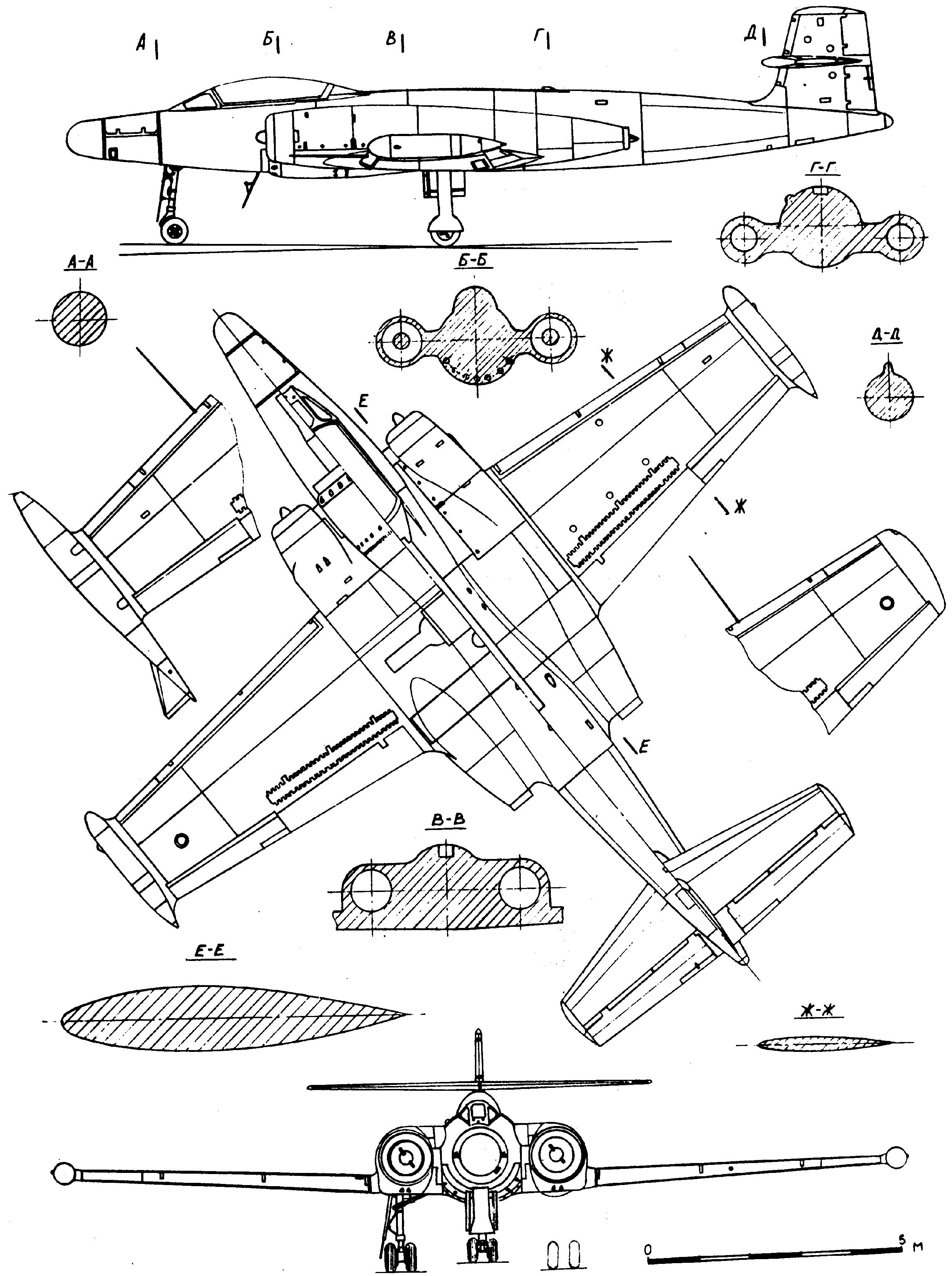

- Crew: 2 (Pilot and Navigator/Radar Operator)

- Length: 16.5 meters (54 ft 2 in)

- Wingspan: 17.4 meters (57 ft 2 in) - note the extended wingtips on the Mk 5

- Max Speed: 1,046 km/h (650 mph) at sea level

- Service Ceiling: 13,700 meters (45,000 ft)

- Armament: 2 wingtip pods containing 29 x 2.75-inch rockets each.

To truly grasp why this aircraft holds such a place in Canadian history, one must look past its utilitarian lines. It represents the peak of indigenous Canadian aerospace manufacturing—a feat of engineering that provided a reliable shield for an entire continent during the most tense years of the 20th century. While the Arrow is the ghost that haunts Canadian aviation, the Canuck is the workhorse that actually built the legacy.