Silver is weird. Most of us think of it as just a shiny metal for jewelry or those fancy spoons your grandmother refuses to use, but in the world of physics and chemistry, it's a bit of a moving target. If you open a standard periodic table, you'll see a number: 107.8682. That is the atomic mass of silver, or at least the average version of it we’ve agreed upon for the sake of not losing our minds during lab experiments.

But here’s the kicker. If you could zoom in and grab a single atom of silver, you would never, ever find one that actually weighs 107.8682 atomic mass units. It’s physically impossible.

Silver doesn't exist as a single "thing" in nature. It’s a mixture. It's a cocktail of isotopes that have been floating around the universe since some supernova went off billions of years ago. When we talk about the mass of Ag (its chemical symbol, from the Latin argentum), we’re really talking about a weighted average. It’s like saying the average human has 1.99 legs. It’s statistically true, but you’d be hard-pressed to find that specific person on the street.

The Two Flavors of Silver

Nature decided to give silver two stable isotopes. You’ve got Silver-107 and Silver-109.

They are almost perfectly balanced. Silver-107 makes up about 51.8% of the stuff you find in the earth's crust, while Silver-109 takes up the remaining 48.2%. Because they are so close in abundance, the atomic mass of silver ends up sitting right in the middle of them.

Why do they weigh different amounts? Neutrons. Every silver atom has 47 protons. That’s what makes it silver. If you add a proton, it becomes cadmium; take one away, it’s palladium. But you can cram extra neutrons into that nucleus without changing the chemical "soul" of the atom. Silver-107 has 60 neutrons. Silver-109 has 62. Those two extra neutrons are the reason the mass isn't a round number.

Interestingly, there are dozens of other silver isotopes, but they are all radioactive junk. They exist for a few seconds—or maybe days—in a nuclear reactor before they decay into something else. But the two stable ones? They’ve been here since the Earth formed.

👉 See also: Astronauts Stuck in Space: What Really Happens When the Return Flight Gets Cancelled

The IUPAC and the "Standard" Weight

Every few years, a group called the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) gets together to argue about these numbers. It sounds incredibly boring, but it matters for high-precision science. In 2011, they actually updated the way we express the atomic mass of silver and several other elements.

Instead of a single fixed number, they started using intervals for some elements because the isotopic composition can actually change depending on where you find the sample. If you find silver in a hydrothermal vein in Mexico, is the ratio of isotopes exactly the same as silver found in a Norwegian mine? Usually, yes, but for some elements like boron or lithium, it varies enough to mess up sensitive calculations. For silver, 107.8682(2) is the gold standard (pun intended), where that little (2) represents the uncertainty in the last digit.

Why This Number Actually Matters in the Real World

You might think this is just academic fluff. It isn't.

Take the pharmaceutical industry. Silver has massive antimicrobial properties. Silver nitrate is used in eye drops for newborns and in bandages for burn victims. When chemists are synthesizing these compounds, they have to use the atomic mass of silver to calculate "moles." If your mass is off, your concentration is off. In medicine, being "off" is a bad thing.

Then there’s the tech sector.

Silver is the most conductive element on the periodic table. Better than gold. Better than copper. Your smartphone, the laptop you’re likely reading this on, and the solar panels on your neighbor’s roof all rely on silver paste and silver wiring. When engineers are depositing silver layers that are only a few atoms thick—using a process called physical vapor deposition—they need to know the exact mass of the atoms they are flinging at a substrate.

✨ Don't miss: EU DMA Enforcement News Today: Why the "Consent or Pay" Wars Are Just Getting Started

The Mystery of the Missing Mass

If you add up the mass of 47 protons and 60 neutrons, you get a number. But surprisingly, the Silver-107 atom weighs less than the sum of its parts.

This is called the mass defect.

When those protons and neutrons smash together to form a nucleus, a tiny bit of their mass is converted into energy. This is Einstein’s $E=mc^2$ in action. That "lost" mass is the binding energy that holds the atom together. If that energy wasn't released, the protons—which are all positively charged—would repel each other and the atom would fly apart. So, the atomic mass of silver is actually a testament to the fundamental forces holding the universe together. It’s literally missing weight that turned into the "glue" of reality.

Silver in the Lab: A Practical Example

Let's say you're a chemistry student. You’re tasked with performing a silver nitrate precipitation to find the amount of chloride in a water sample. You weigh out your silver.

You’re using the molar mass, which is numerically equivalent to the atomic mass but expressed in grams per mole ($g/mol$).

$107.8682 \text{ grams} = 1 \text{ mole of silver atoms}$

🔗 Read more: Apple Watch Digital Face: Why Your Screen Layout Is Probably Killing Your Battery (And How To Fix It)

That’s $6.022 \times 10^{23}$ atoms. That is a staggering number. If you had that many unpopped popcorn kernels, they would cover the entire Earth in a layer nine miles deep. Yet, because the atomic mass of silver is relatively high compared to something like carbon (which is only 12), all those atoms fit into a small pile of metal that weighs about as much as a standard cell phone.

Common Misconceptions About Silver's Weight

I’ve seen people get confused between atomic mass and atomic number. It’s easy to do.

- Atomic Number: 47 (This is the identity. Protons only.)

- Atomic Mass: ~107.87 (This is the weight. Protons + Neutrons + binding energy.)

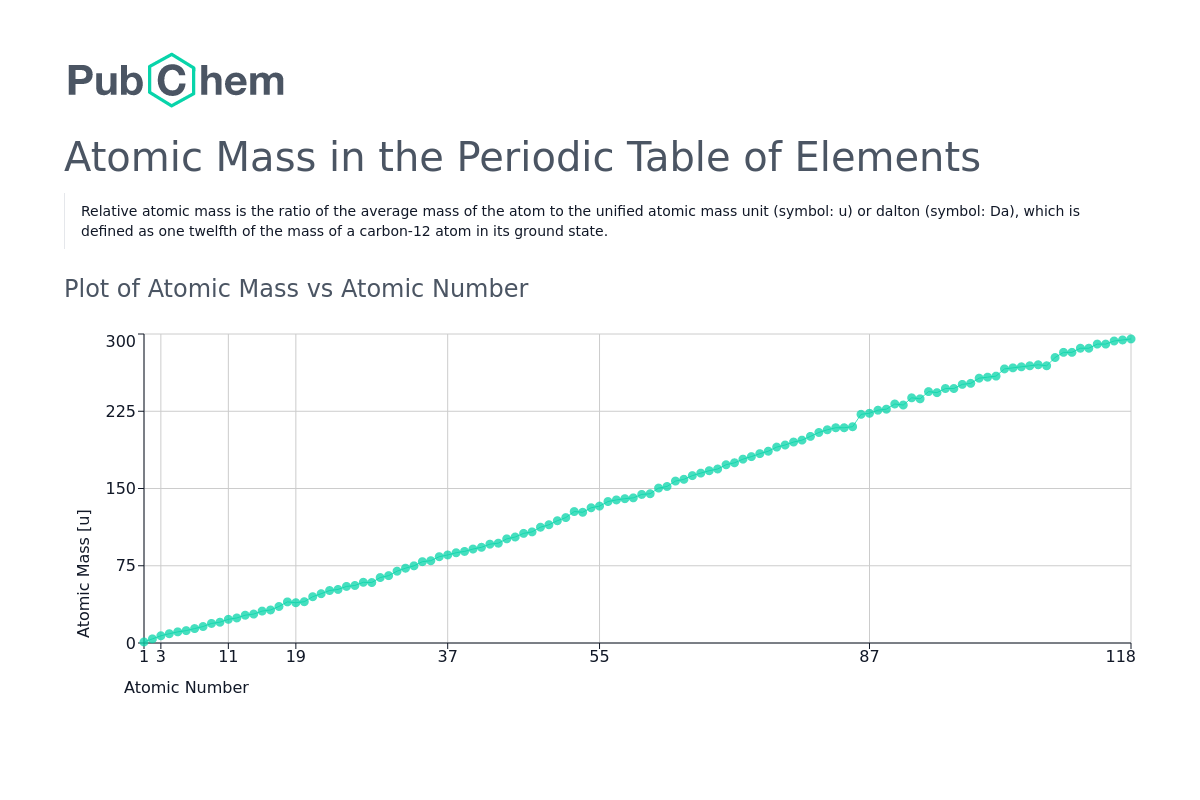

Another weird one? People think silver is "heavy" because it’s a metal. While it’s denser than water, its atomic mass is mid-range. Lead is 207. Gold is 197. Compared to the heavy hitters at the bottom of the table, silver is a lightweight. But compared to the aluminum in your soda can (mass of 26.98), silver is a tank.

How to Use This Information

If you are a student, stop trying to memorize the number 107.8682. Just remember it's "about 108." Most chemistry teachers are fine with that unless you're doing analytical work.

If you are an investor or a stacker of physical bullion, the atomic mass doesn't change the price of your 1-ounce bar, but it does determine the purity. "Fine silver" is .999 pure. That means for every 1,000 atoms in that bar, 999 of them are silver isotopes (107 or 109) and one might be a stray copper or nickel atom that didn't get refined out.

Actionable Insights for Science Enthusiasts

- Check your Periodic Table version: If your table says silver is exactly 107.87, it’s a simplified version. For precision work, always look for the IUPAC four-decimal value.

- Understand the Isotope Ratio: If you’re ever looking at mass spectrometry data, don't look for a peak at 107.86. You won't find it. Look for two distinct peaks: one near 107 and one near 109.

- Conductivity Calculations: If you're tinkering with DIY electronics or electroplating, remember that silver's efficiency is tied to its atomic density, which is a direct byproduct of its mass and its crystal structure (face-centered cubic, if you're curious).

The atomic mass of silver isn't just a static figure in a book. It’s a snapshot of a cosmic balance between two different types of atoms that have been mixed together for billions of years. Whether it's in your phone, your teeth (mercury amalgams often contain silver), or the mirror you looked in this morning, those 107 and 109 isotopes are doing the heavy lifting.

Next time you hold a silver coin, realize you aren't holding one type of matter. You're holding a nearly 50/50 split of two different cosmic remnants, averaged out to the number 107.8682. Pretty cool for a piece of "plain" metal.

To dive deeper into how these masses affect chemical reactions, you should practice calculating molar ratios using the latest NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology) values. Always verify the source of your periodic table when performing gravimetric analysis, as older charts might not reflect the most recent IUPAC refinements regarding isotopic abundance.