You probably don't think about cesium atoms when you're heating up a frozen burrito at 12:15 PM in Chicago. Why would you? But the reality is that the atomic clock Central Time Zone sync is basically the invisible glue holding your digital life together. If that connection slips by even a fraction of a second, your GPS goes haywire, your bank transfers fail, and the power grid might literally start humming the wrong tune. It's weird to think about. We just look at our phones and assume the time is "the time."

Most people think time is just a thing that happens. It isn't. Time is a measurement we have to fight for. In the United States, that fight happens mostly in Boulder, Colorado, at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). They operate the primary frequency standard, which is a fancy way of saying they have the world's most accurate stopwatch. This clock, known as NIST-F1 (and later NIST-F2), doesn't use gears or springs. It uses the vibration of cesium atoms to define what a "second" actually is.

The Madness of Measuring a Single Second

What is a second? Honestly, it’s a bit of a nightmare to define. Back in the day, we just chopped up the rotation of the Earth. But the Earth is a bit of a mess—it wobbles, it slows down because of the moon, and it speeds up when the ice caps melt. It’s unreliable. So, scientists turned to the atom. Specifically, the Cesium-133 atom.

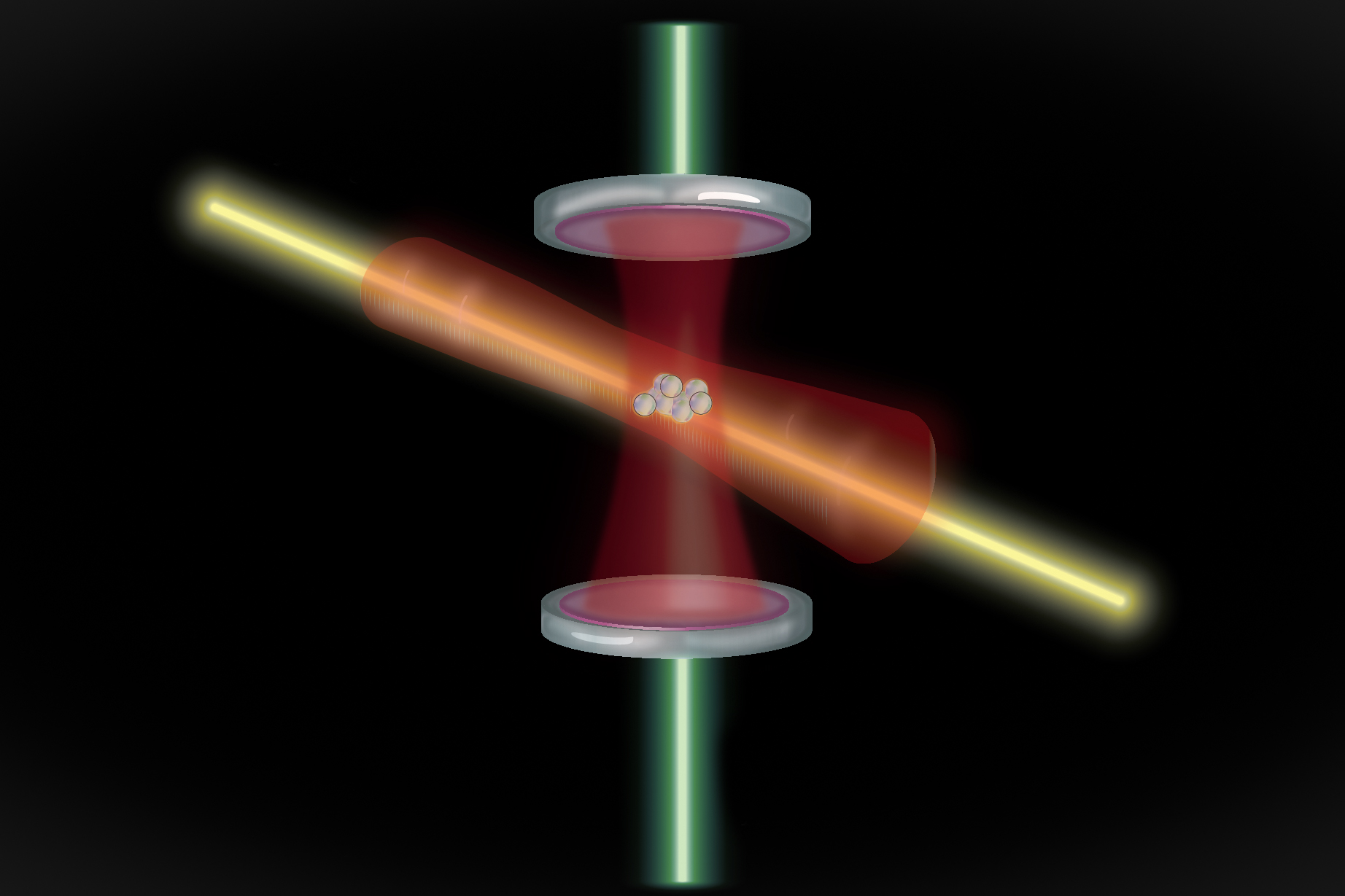

When you hit a cesium atom with a very specific frequency of microwave radiation, the electrons jump between energy levels. They do this exactly 9,192,631,770 times per second. That's not an approximation. That is the definition. If your microwave frequency is off by a hair, the atoms don't jump. This is how the atomic clock Central Time Zone data stays so incredibly precise. The NIST clocks are so accurate they wouldn't gain or lose a second in 300 million years. That's longer than dinosaurs have been gone.

How the Signal Gets to Your Kitchen

You’ve seen those "Atomic Clocks" at Walmart or on Amazon, right? The ones that say they’ll automatically set themselves? They aren't actually atomic clocks themselves. They’re just radio receivers.

In Fort Collins, Colorado, NIST runs a radio station called WWVB. It’s a massive array of antennas that blasts a 60 kHz signal across the entire North American continent. If you live in the Central Time Zone—places like Dallas, St. Louis, or Winnipeg—your clock is listening for that signal in the middle of the night.

Atmospheric conditions are better for radio waves when the sun is down. That’s why your "Atomic" wall clock usually updates at 2:00 AM. It catches a pulse from Colorado, realizes it’s 0.4 seconds slow, and adjusts. Basically, the atomic clock Central Time Zone experience is just your devices eavesdropping on a government radio broadcast.

Why the Central Time Zone is a Unique Challenge

The Central Time Zone is huge. It stretches from the frigid borders of Nunavut down to the tropical heat of Veracruz, Mexico. Because it’s so sprawling, the signal from the NIST transmitters has to travel different distances to reach everyone.

Radio waves travel at the speed of light, but they still take time. If you’re in Nashville, the signal takes a few milliseconds longer to reach you than if you’re in western Kansas. For your wall clock, that doesn't matter. You won't notice a three-millisecond difference in your 8:00 AM meeting. But for a high-frequency trading server in Chicago? That's an eternity.

Chicago is the heart of the Central Time Zone's financial world. In the world of algorithmic trading, millions of dollars are made or lost in the time it takes a photon to travel a hundred miles. These institutions can't rely on a radio signal from Fort Collins. They use GPS.

💡 You might also like: Why the Sony DR-11 Still Sounds Better Than Your Modern Earbuds

The Secret Life of GPS Satellites

Most people think GPS is for maps. It’s actually a network of flying atomic clocks. Each GPS satellite has multiple atomic clocks on board (usually rubidium or cesium). They beam down a time stamp. Your phone receives signals from at least four satellites, calculates the "time of flight" for those signals, and uses the difference to figure out exactly where you are on Earth.

If the atomic clock Central Time Zone synchronization in a GPS satellite was off by even one-millionth of a second, your location on Google Maps would be wrong by about 300 meters. You’d be looking for a Starbucks and end up in a river.

Network Time Protocol (NTP): The Internet’s Pulse

If you’re on a laptop right now, you aren't using WWVB radio or a GPS antenna. You’re using NTP. Your computer sends a ping to a "Stratum 1" server. A Stratum 1 server is a computer directly connected to an atomic clock or a GPS timing source.

The protocol is actually pretty clever. It accounts for the delay of the internet itself. It measures how long the request took to go out and come back, divides it by two, and adjusts your system clock. This keeps the atomic clock Central Time Zone offset on your MacBook or PC within about 10 milliseconds of the "truth."

- Stratum 0: The actual atomic clock (the source).

- Stratum 1: Servers directly attached to the source.

- Stratum 2: Servers that talk to Stratum 1 servers (most public NTP servers).

Daylight Savings and the Great Confusion

Every year, we do this weird dance where we jump forward or back. It's a logistical nightmare for programmers. Atomic time—specifically International Atomic Time (TAI)—doesn't care about seasons. It just ticks.

But humans like the sun to be in the sky when they're awake. So we use Coordinated Universal Time (UTC). UTC is based on atomic time but includes "leap seconds" to keep it aligned with the Earth's slowing rotation. When the Central Time Zone switches from CST (Central Standard Time) to CDT (Central Daylight Time), the atomic clocks don't change. We just change the offset.

Basically, the atomic clock Central Time Zone value is always UTC -6 hours in the winter and UTC -5 hours in the summer. If you ever want to see a software engineer cry, ask them to write a program that handles time zone transitions across different historical years. It’s a mess of edge cases.

The Power Grid’s Obsession with Microseconds

This is the part that usually surprises people. The power grid in the Central United States—the Midcontinent Independent System Operator (MISO)—relies on atomic timing to keep the lights on.

Electricity travels as an alternating current (AC). In North America, it oscillates at 60 Hz. All the generators in the Central Time Zone have to be perfectly synchronized. If one generator is slightly out of phase, it doesn't just "work less"—it can actually be destroyed by the other generators on the grid.

Engineers use "synchrophasors" to monitor the grid. These devices use GPS atomic timing to take 30 measurements per second across thousands of miles. By comparing the exact time-stamped phase of the electricity, they can spot a blackout before it happens. Without the atomic clock Central Time Zone precision, the grid would be blind.

Real-World Nuance: Is It Ever Wrong?

Can an atomic clock be wrong? Technically, yes, but not in the way you think. Usually, the "error" comes from Einstein’s Theory of Relativity.

Time moves slower when you’re closer to a massive object (like Earth) and faster when you move quickly. Atomic clocks are so sensitive they can detect the difference in time between the floor and the ceiling of a lab. This is called gravitational time dilation.

👉 See also: The Discovery of the Double Helix: What the Textbooks Usually Get Wrong

When NIST syncs the atomic clock Central Time Zone standard, they have to account for the altitude of the clock. A clock in high-altitude Denver ticks slightly faster than one in sea-level New Orleans. To have a single "national time," scientists have to mathematically "flatten" the clocks to a theoretical sea-level surface called the geoid.

Surprising Details About NIST Radio Stations

The Fort Collins station (WWVB) is actually under constant threat from budget cuts. A few years ago, there was a proposal to shut it down to save money. The "timekeeping community" went ballistic.

Thousands of legacy systems—ranging from irrigation controllers in Nebraska to old wall clocks in Florida—depend on that 60 kHz signal. If NIST turned off the signal, millions of devices would simply stop updating. While the internet (NTP) and GPS are the modern standards, that old-school radio signal is still the backbone for basic infrastructure.

How to Manually Sync to the Source

If you want the absolute truth, you don't look at your watch. You go to Time.gov. This site is run by NIST and the US Naval Observatory. It shows you the exact time in the atomic clock Central Time Zone and even tells you how much "network delay" your browser is currently experiencing.

When you see that digital display ticking, you’re looking at the average of dozens of atomic clocks distributed across the country. It’s the closest thing to "the truth" humans have ever invented.

Practical Steps for Staying Synced

Living in the Central Time Zone means you're in one of the most stable regions for NIST radio reception, but you can still run into issues.

- Position your radio-controlled clocks: If you have an "Atomic" wall clock that isn't updating, move it to a window that faces West toward Colorado. Metal siding or heavy concrete can block the 60 kHz signal.

- Check your server's NTP settings: For small business owners or IT hobbyists in the Central US, don't just rely on a single time server. Configure your devices to use

pool.ntp.org, which automatically finds the closest, most stable atomic-synced server to your location. - Verify GPS health: If you rely on GPS for precision timing (like in photography or amateur radio), remember that solar flares can disrupt the signal. During high solar activity, the "atomic" accuracy of your GPS receiver might degrade temporarily.

- Use Time.gov for manual checks: If you need to set a mechanical watch or calibrate a device, use the official NIST portal. It’s the gold standard for the atomic clock Central Time Zone reference.

Time isn't just a number on a screen. It's a constant, high-speed calculation involving atoms, satellites, and radio waves. Next time you see your clock flip from 11:59 to 12:00, just remember there’s a vibrating atom in a vacuum chamber in Colorado making sure that moment is exactly when it's supposed to be.