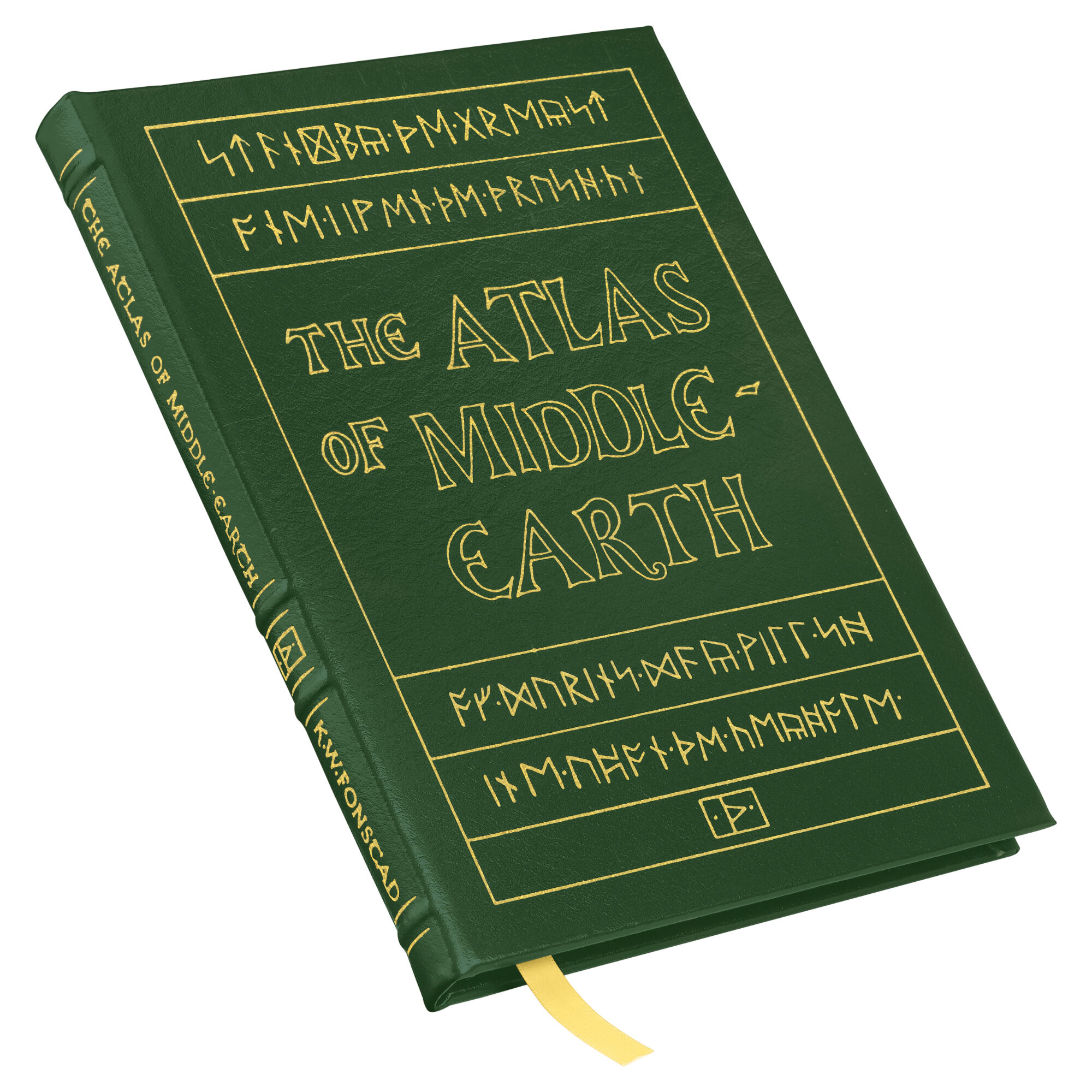

Reading J.R.R. Tolkien without a map is like trying to navigate London during a blackout with nothing but a vague sense of direction and a lot of hope. You might get where you're going, but you’ll miss the sheer scale of the journey. For decades, fans have turned to one specific book to bridge that gap. The Atlas of Middle-earth by Karen Wynn Fonstad isn't just some glossy coffee table book filled with pretty pictures. It’s a work of grueling, obsessive cartography. Honestly, it’s basically the gold standard for fantasy world-building analysis.

If you’ve ever wondered exactly how many miles Frodo walked while carrying a piece of jewelry that weighed more than his own soul, or why the geography of Beleriand seems so confusing compared to the Third Age, Fonstad is the one who did the math. She didn't just draw lines on a page. She looked at the geology. She looked at the weather patterns. She tracked the moon phases Tolkien meticulously noted in his drafts.

The Woman Behind the Maps

Karen Wynn Fonstad wasn't a random illustrator hired to make "cool" maps for a franchise. She was a cartographer with a Master’s degree from the University of Oklahoma. She approached Middle-earth like a real place. That matters. When you look at her work in The Atlas of Middle-earth, you aren't looking at "fan art." You’re looking at a geographical survey of a fictional continent conducted with the same rigor you'd apply to the Rocky Mountains.

Most people don't realize how much of a struggle it was to compile this. Tolkien was a genius, but he was also a man who revised his work constantly. His son, Christopher Tolkien, spent years cataloging his father's messy notes in The History of Middle-earth series. Fonstad had to sift through those layers of drafts—some of which contradicted each other—to find a cohesive spatial reality. She died in 2005, but her work remains the definitive topographical guide. Even the designers for the Peter Jackson films leaned on her logic to understand how the proximity of Minas Tirith to Osgiliath actually worked in a physical space.

Why The Atlas of Middle-earth Still Matters

A lot of fantasy maps are just "here is a mountain, here is a forest." Fonstad’s work is different. She provides thematic maps. You get maps of the First Age, the Second Age, and the Third Age. You see the world literally breaking apart during the War of Wrath. It's visceral.

💡 You might also like: Is Steven Weber Leaving Chicago Med? What Really Happened With Dean Archer

The level of detail is, frankly, insane. She includes floor plans. Have you ever wanted to see the layout of Bag End or the internal structure of Orthanc? She drew them. She mapped the pathways through Moria, which is a three-dimensional nightmare of a location. Tolkien’s descriptions are vivid, but trying to visualize the Bridge of Khazad-dûm in relation to the Endless Stair is hard for a human brain. Fonstad makes it click.

One of the coolest parts is the "Pathways" section. It’s not just a map of the world; it’s a timeline. She tracks the movements of the Fellowship day by day. You can see where they camped, where they fought, and where they spent twenty-four hours just trying not to freeze to death on Caradhras. It turns a static book into a living, moving adventure. You realize that the distance between Bree and Rivendell is massive. It wasn't a weekend hike. It was a grueling, terrifying trek through the wilderness.

Common Misconceptions About Tolkien’s Geography

People often think Middle-earth is a whole planet. It’s not. It’s a continent (well, a part of one) on a planet called Arda. Fonstad explains this beautifully. She shows the transition from a flat world to a round world—a cosmic shift in Tolkien’s lore that most casual fans completely miss.

There’s also this weird idea that Mordor is just a square box of mountains because Tolkien was "lazy." If you look at the geological maps in The Atlas of Middle-earth, you see the volcanic activity and the tectonic logic behind the Ash Mountains and the Mountains of Shadow. It’s not a box; it’s a series of natural barriers formed by the catastrophic power of Melkor and Sauron.

📖 Related: Is Heroes and Villains Legit? What You Need to Know Before Buying

Some critics argue that Fonstad took too many liberties. Since Tolkien didn't provide a scale for every single puddle in the Shire, she had to interpolate. She had to guess. But her guesses are informed by actual science. If Tolkien says a character walked from Point A to Point B in three days, Fonstad calculates the average walking speed of a Hobbit versus a Man over hilly terrain to determine the distance. That’s dedication.

How to Use the Atlas While Reading

Don't just read the Atlas cover to cover like a novel. That’s a recipe for a headache. The best way to use it is as a companion. When you’re reading The Silmarillion and you get lost in the list of names—who is where, which Elf King is in which hidden city—open the Atlas.

Keep it on your lap.

When Beren and Lúthien are crossing the Ered Gorgoroth, look at Fonstad's map of the First Age. You’ll see the "Mountains of Terror" and realize they weren't just hills. They were a nightmare of sheer cliffs and spiders. It adds a layer of stakes to the narrative that text alone sometimes struggles to convey.

👉 See also: Jack Blocker American Idol Journey: What Most People Get Wrong

- Start with the regional maps. Get the "big picture" of the continent.

- Move to the site plans. Look at the layout of Helm's Deep before you read the battle. It changes how you visualize the tactics.

- Check the travel chronologies. Use them to see how far apart the characters are from each other at any given moment. While Frodo is in Cirith Ungol, where is Aragorn? The Atlas tells you.

The Evolution of the Maps

The first edition came out in 1981. It was good, but it lacked the wealth of information Christopher Tolkien eventually released in the later volumes of The History of Middle-earth. The "Revised Edition" is what you want. It’s the one with the brown-toned cover. It incorporates the data from the 12-volume history series, making it much more accurate to Tolkien's final (or most developed) visions of his world.

It's actually kind of funny how much Tolkien struggled with his own maps. He famously complained about having to "make the story fit the map" because he'd sometimes write himself into a corner geographically. Fonstad solves those puzzles. She reconciles the "textual errors" by finding the most logical physical layout that satisfies the story’s requirements.

Real-World Impact on Fantasy Cartography

Every fantasy map you see today—from A Song of Ice and Fire to The Wheel of Time—owes something to the standard Fonstad set. She proved that a fictional map could be more than a decorative piece. It could be a tool for literary analysis.

Think about the sheer scale of the waste in the Brown Lands. In the book, it’s a description of desolation. In The Atlas of Middle-earth, it’s a visual representation of the ecological cost of war. You see the "scars" on the land. It makes the environmental themes in Tolkien's work stand out much more sharply.

Actionable Next Steps for Fans

If you're looking to elevate your understanding of Tolkien's world, don't just rely on the small, folded maps in the back of your paperbacks. They’re fine for a general idea, but they lack depth.

- Acquire the Revised Edition: Ensure you have the version published after the early 90s. This contains the corrections based on The History of Middle-earth volumes.

- Track the "Tale of Years": Use the Atlas alongside Appendix B in The Return of the King. Matching the dates to the maps creates a 4D view of the story.

- Study the First Age maps first: Most people find The Silmarillion difficult because they can't visualize the shifting borders. Spend thirty minutes with the "Elder Days" section before starting that book. It makes the "Beleriand" chapters significantly easier to digest.

- Look at the Climate and Terrain sections: Fonstad includes fascinating notes on the vegetation and weather of Middle-earth. Understanding the rain shadow effect of the Misty Mountains explains why the lands to the east are so much drier.

The beauty of this book is that it treats the Legendarium with the respect it deserves—not as a collection of fairy tales, but as a lost history of a very real-feeling world.