If you’ve ever hummed that old Johnny Mercer tune about the "Atchison, Topeka, and the Santa Fe," you probably have a romanticized image of steam engines chugging through Kansas wheat fields. It’s a nice vibe. But honestly, the reality of the Atchison Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad (ATSF) was way more grit, guts, and aggressive real estate speculation than catchy lyrics suggest. It wasn't just a train line; it was a massive, sprawling corporate empire that basically dictated where cities lived or died across the Southwest.

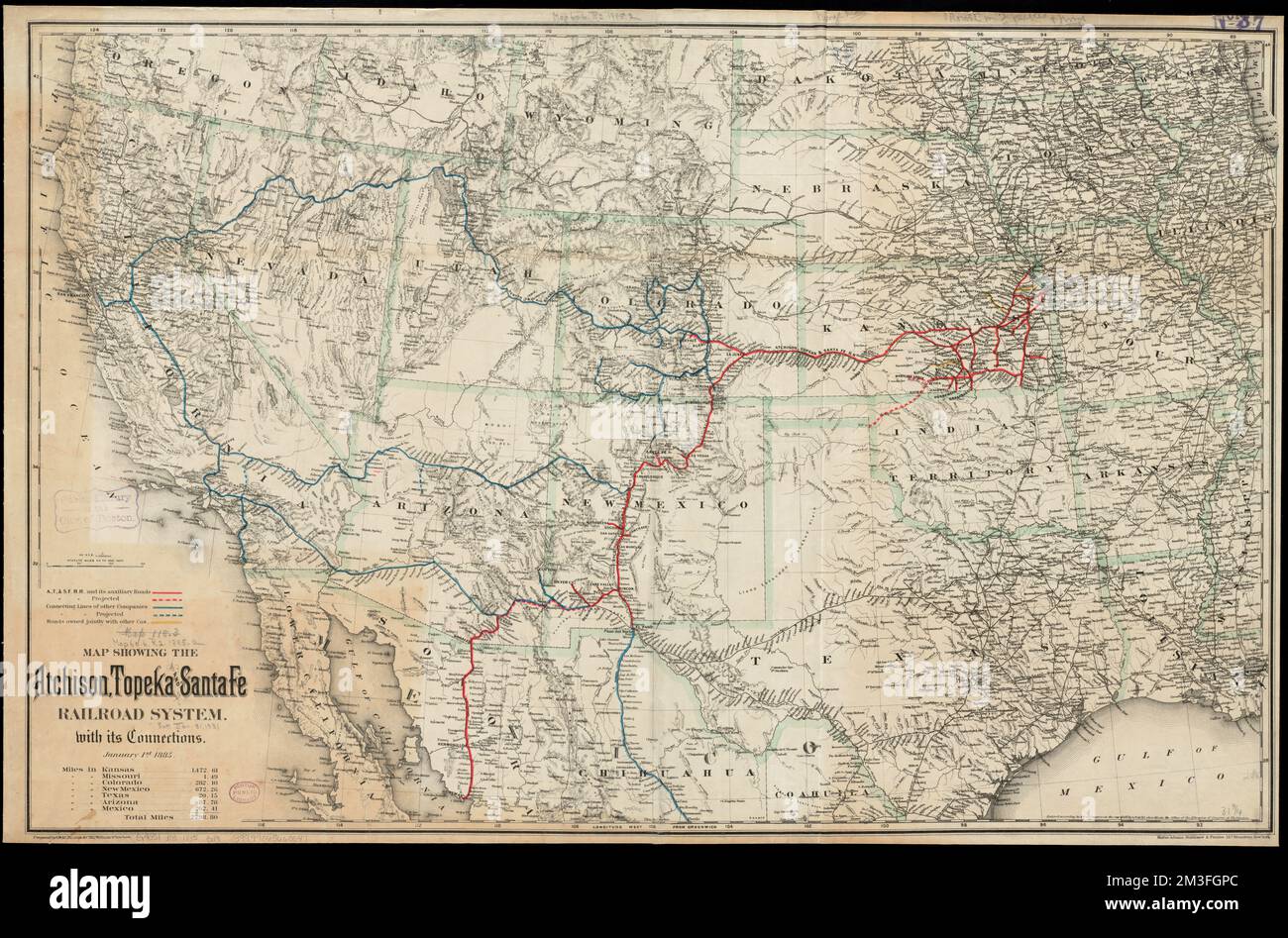

The ATSF didn't actually start in Santa Fe. That’s the first thing people usually get wrong. When Cyrus K. Holliday chartered the thing in 1859, it was a dream on paper during a time when "bleeding Kansas" was barely a state. He wanted to connect Kansas to the Pacific, but the tracks didn't even reach Topeka until 1869. From there, it was a mad dash. They were competing against the Denver & Rio Grande, fighting literal "railroad wars" over mountain passes. It was chaotic. It was messy. It was exactly how the West was actually won—not by cowboys, but by track-layers and surveyors.

The Royal Gorge War and the Fight for the West

You can't talk about the Atchison Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad without mentioning the 1878 Royal Gorge War. This wasn't some boardroom dispute with lawyers in suits. It involved armed guards, stone forts, and hired guns. The ATSF and the Denver & Rio Grande (D&RG) both wanted the narrow passage of the Royal Gorge in Colorado. There was only room for one set of tracks.

The ATSF hired Bat Masterson—yeah, the actual frontier lawman—to lead a group of gunmen to protect their interests. It sounds like a movie script, but it’s 100% historical fact. Eventually, the courts had to step in because the physical violence was getting out of hand. The "Treaty of Boston" finally settled it in 1880. The ATSF agreed not to build into Denver or the mountain mining districts for a decade, and in exchange, they got the route to New Mexico.

This pivot was huge.

By losing the fight for the Colorado Rockies, the Santa Fe was forced to look south and west. This is why we have the iconic "Southwest" aesthetic today. The railroad realized that if they couldn't just haul silver and coal, they had to haul people. They had to sell a dream.

💡 You might also like: Wingate by Wyndham Columbia: What Most People Get Wrong

How Fred Harvey and the "Harvey Girls" Changed Everything

Before the Atchison Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad teamed up with Fred Harvey, eating on a train was a nightmare. You'd pull into a station, have fifteen minutes to bolt down some rancid meat and stale bread, and hope you didn't get food poisoning before the next stop.

Harvey changed the game.

He opened the first Harvey House restaurant in the Topeka station in 1876. The deal was simple: the railroad provided the space, and Harvey provided high-quality food and "civilized" service. This birthed the Harvey Girls—young, educated women who moved West to work as waitresses. They had strict conduct codes, lived in supervised dorms, and basically became the vanguard of the female workforce in the American West.

Why the Harvey Houses Mattered

- Standardization: You knew the coffee would be good whether you were in Albuquerque or Barstow.

- Architectural Identity: They used "Mission Revival" and "Santa Fe Style," which is why every tourist trap in New Mexico looks the way it does now.

- Tourism Marketing: They didn't just sell tickets; they sold "The Great Southwest."

The ATSF was incredibly savvy at marketing. They hired famous painters to capture the Grand Canyon and the Painted Desert, then used those images on calendars and travel brochures. They turned the Navajo and Hopi cultures into a "destination." While this was definitely exploitative in many ways, it’s the reason the Grand Canyon became a National Park and a global bucket-list item. The railroad literally built the El Tovar Hotel right on the rim.

The High-Speed "Super Chief" Era

Skip forward to the 1930s. The Atchison Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad became the "Train of the Stars." If you were a Hollywood mogul or a starlet traveling between LA and Chicago, you took the Super Chief.

📖 Related: Finding Your Way: The Sky Harbor Airport Map Terminal 3 Breakdown

This wasn't just a train. It was a rolling five-star hotel.

Launched in 1936, the Super Chief featured sleek, streamlined Diesel-electric locomotives and "Pleasure Domes" with panoramic views. The dining car, the "Turquoise Room," was legendary. You could get a charcoal-broiled steak and a bottle of fine wine while hurtling across the Mojave Desert at 90 miles per hour. It was the peak of American rail travel.

But even then, the writing was on the wall. The same technology that made the trains faster—the internal combustion engine—was being shoved into cars and planes. The ATSF saw the decline of passenger rail coming long before most other lines. They leaned hard into freight. They were pioneers in "intermodal" shipping, which is just a fancy way of saying they put truck trailers on flatcars. If you see a BNSF train today with Amazon or UPS containers, you’re looking at the direct evolution of the ATSF’s survival strategy.

What Happened to the Santa Fe?

The end of the independent Atchison Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad came in 1995. It merged with the Burlington Northern Railroad to become BNSF Railway.

Some railfans were devastated. The iconic "Warbonnet" paint scheme—that beautiful red and silver nose on the locomotives—started to disappear, replaced by BNSF orange. But the DNA of the Santa Fe is still everywhere.

👉 See also: Why an Escape Room Stroudsburg PA Trip is the Best Way to Test Your Friendships

The main line from Chicago to Los Angeles, known as the "Transcon," is still one of the busiest and most vital pieces of infrastructure in the world. It’s a double-tracked (and in some places triple-tracked) high-speed freight corridor. It’s the reason your gadgets from overseas get to the Midwest so fast.

Common Misconceptions

- The "Santa Fe" didn't go to Santa Fe: For a long time, it didn't! The main line actually bypassed the city of Santa Fe because the geography was too difficult. They had to build a "spur" line from Lamy, New Mexico, just to reach the city that gave the railroad its name.

- It wasn't just one company: Like most big railroads, it was a "system" made up of dozens of smaller lines that were bought out, swallowed up, or leased over a century.

- It wasn't just about trains: The ATSF owned land companies, oil wells, and even a fleet of tugboats in San Francisco Bay.

Why You Should Care Today

You can still ride the Atchison Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad route. Sort of. Amtrak’s Southwest Chief follows the old ATSF tracks almost exactly.

If you take that trip from Chicago to LA, you aren't just looking at scenery. You're looking at the literal backbone of the American economy. You pass through the Raton Pass, where the ATSF beat out the D&RG. You see the old Harvey Houses—some restored, like the La Posada in Winslow, Arizona, and others crumbling into the desert.

It’s a lesson in how big business actually shaped the map. The reason towns like Dodge City, Amarillo, and Albuquerque are hubs isn't an accident of geography. It’s because a surveyor for the Santa Fe marked a spot on a map and decided that’s where the water stop should be.

Practical Steps for History Buffs and Travelers

If you want to experience this history without just reading a Wikipedia page, here is what you actually do:

- Visit the California State Railroad Museum in Sacramento. They have some of the most pristine ATSF equipment in existence, including a dining car that makes modern airline food look like a crime.

- Stay at a restored Harvey House. The La Posada Hotel in Winslow is the crown jewel. It was designed by Mary Colter, the architect who basically invented the "National Park" look. It’s a working hotel, not a dusty museum.

- Ride the Southwest Chief. Don't do it for the speed (it’s slow). Do it for the "Wine and Cheese" tasting in the lounge car while crossing the Kansas plains at sunset.

- Check out the Kansas State Historical Society. If you’re a real nerd for the technical stuff, they hold the official corporate archives of the ATSF. We’re talking maps, payrolls, and original engineering drawings.

- Explore the "Grand Canyon Railway." This is a heritage line that runs from Williams, Arizona, to the South Rim. It uses the old ATSF tracks and gives you a taste of what it was like for tourists in 1901.

The Atchison Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad didn't just build tracks; it built the cultural identity of a third of the United States. It’s the reason we associate New Mexico with turquoise jewelry and why Los Angeles grew from a dusty town into a megalopolis. The engines might be orange now, but the ghost of the silver Warbonnet still runs that line every single day.