You've seen it a thousand times. A kid walks into a room and does that specific, weird nose-crinkle their dad does. Or maybe a daughter inherits her mother’s sharp wit and even sharper temper. We use the phrase apple doesn't fall too far from the tree as a sort of shorthand for "like parent, like child," usually with a knowing smirk or a heavy sigh.

But is it just a cliché?

It’s one of those proverbs that feels ancient because it basically is. While the English version gained massive popularity in the 19th century—often linked to Ralph Waldo Emerson—the core sentiment traces back to German and even older roots. It’s a fundamental observation of human nature. We are, to a terrifying or comforting degree, echoes of the people who made us. Honestly, it’s about more than just having the same eye color. It’s about the invisible threads of behavior, temperament, and even the way we handle a crisis.

Where the apple doesn't fall too far from the tree actually comes from

Most people think this is a purely English idiom. It isn't. The phrase has a long history in Germanic languages (Der Apfel fällt nicht weit vom Stamm). Emerson is often credited with bringing it into the American lexicon in 1839. He used it to describe how people are tethered to their origins.

The imagery is perfect. A tree stands tall. Its fruit grows, ripens, and eventually drops. Gravity is the law. Unless there’s a massive storm or a steep hill, that fruit is staying within the shade of the branches that fed it.

In a literal sense, it's about proximity. In a metaphorical sense, it's about the limits of our own autonomy. We like to think we are self-made, but the soil we grew in dictates so much of our nutritional value.

The DNA of it all: Why biology wins

When we talk about the apple doesn't fall too far from the tree, we’re really talking about heritability. Behavioral genetics is a dense field, but the "Big Five" personality traits—openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism—are roughly 40% to 60% heritable. That’s a huge chunk of who you are.

Think about the Minnesota Study of Twins Reared Apart. It’s a landmark piece of research. Researchers found that identical twins who grew up in completely different environments still ended up with eerily similar mannerisms, job interests, and even specific phobias. One pair of twins, famously known as the "Jim Twins," were separated at birth and reunited at age 39. They both had dogs named Toy, both drove Chevrolets, and both suffered from tension headaches.

That’s the tree exerting its influence from miles away.

It’s not just the big stuff. It’s the micro-behaviors. If your parents are prone to anxiety, your nervous system might be "tuned" to a higher frequency from day one. You aren't just copying them; you are physically wired to react to the world in a similar way. This is where the proverb gets a bit heavy. It suggests a lack of choice. If the tree is gnarled and bitter, can the apple ever be sweet?

Breaking the cycle: When the apple rolls down a hill

Sometimes the apple does roll away. We call this "breaking the cycle."

Psychologists often look at "resilience factors." Just because the apple doesn't fall too far from the tree doesn't mean it’s glued to the ground. Epigenetics is the study of how your environment can actually change how your genes work. You might have the "gene" for a certain temperament, but a different environment can effectively flip the switch to "off."

Take a look at the concept of the "black sheep." Usually, this is just an apple that hit a rock upon landing and bounced into a different field. Maybe it was a mentor, a different city, or just a conscious, grueling effort to be different.

But even then, the tree is the reference point. To be the opposite of your parents is still to be defined by them. You’re just the negative image of the original photo. You are still reacting to the tree.

The nuance of "Learned Behavior" vs. "Innate Nature"

We have to distinguish between what's in the blood and what's in the house.

- The Genetic Tree: This is your height, your predisposition to certain diseases, and your baseline temperament.

- The Environmental Tree: This is how you handle money, how you argue with a spouse, and your taste in music.

If a father is a loud-talker and the son grows up to be a loud-talker, is it because of his vocal cords or because he had to shout to be heard at the dinner table? Usually, it's both. The "tree" isn't just a biological entity; it’s a cultural one. Families are their own little islands with their own languages and customs. Breaking those customs feels like a betrayal of the tree itself.

Why we love (and hate) this phrase

We use it for praise: "She’s a brilliant doctor, just like her mom. The apple doesn't fall too far from the tree."

We use it for judgment: "He’s back in jail? Well, the apple doesn't fall too far from the tree."

📖 Related: Beard and Moustache Dye: Why Most Guys Are Doing It Wrong

It’s a double-edged sword. It offers a sense of continuity and legacy, which humans crave. We want to feel like we belong to a lineage. But it also acts as a ceiling. It suggests that our potential is capped by our pedigree.

In the world of business, we see this constantly. Think of the "nepo baby" discourse in Hollywood or the "family business" success stories. We expect the children of greats to be great. When they aren't, it feels like a violation of a natural law. When the son of a legendary quarterback can't throw a spiral, we’re confused. We feel like the apple should have stayed closer.

Real-world examples of the proximity effect

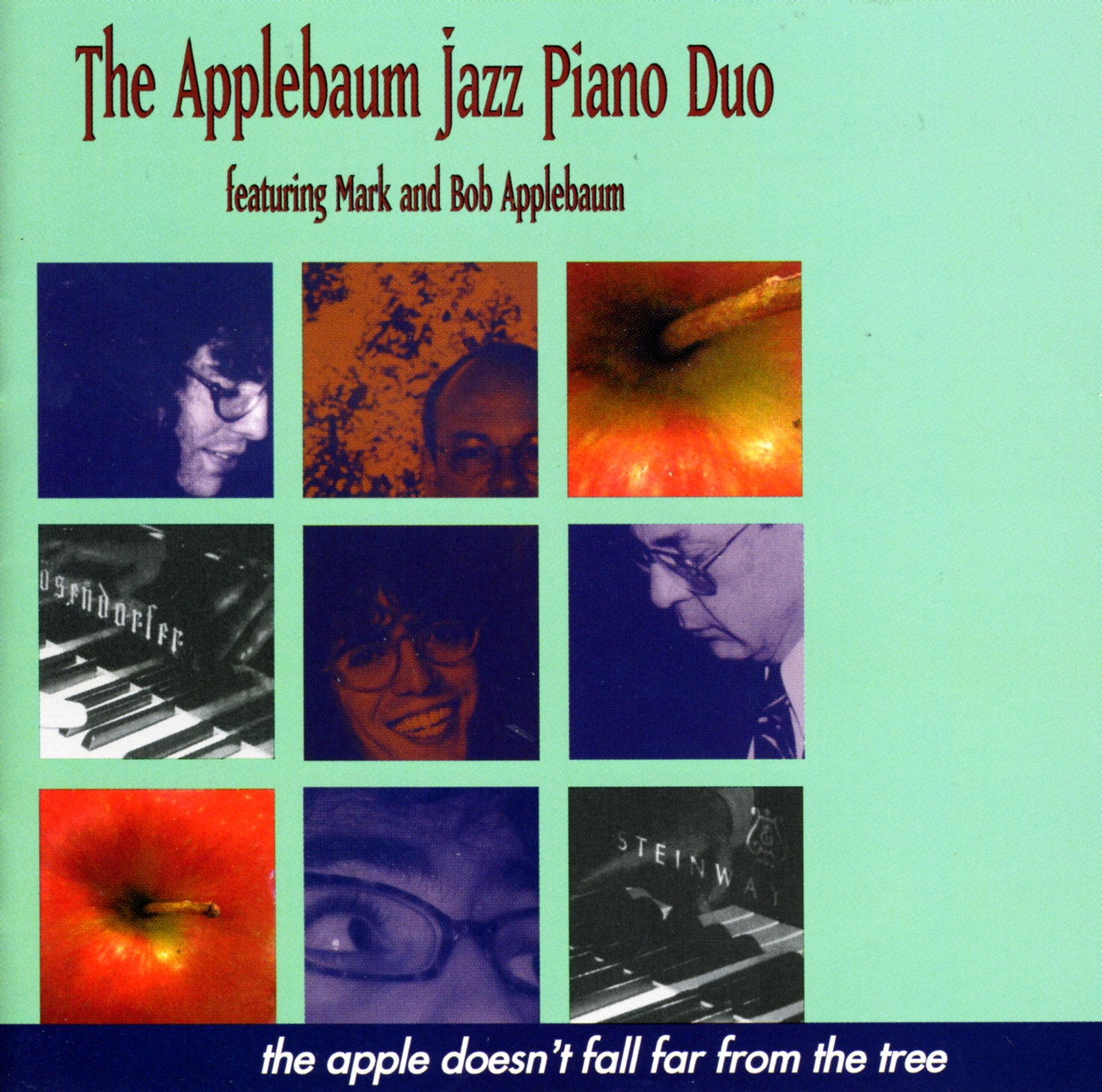

Look at the Wayans family in comedy or the Marsalis family in jazz. These aren't just coincidences. They are environments where the "tree" provided a very specific type of shade. If you grow up around instruments, and you have the rhythmic genes to match, you’re basically destined to fall close to that trunk.

But look at someone like Richard Montañez (the man credited with Flamin' Hot Cheetos). He came from a background of manual labor and poverty. His "tree" didn't suggest corporate executive success. He’s an example of an apple that found a different orchard entirely.

The point is, the apple doesn't fall too far from the tree is a rule of thumb, not a law of physics.

Actionable insights for dealing with your "Tree"

Understanding your origins isn't about blaming your parents or resigning yourself to fate. It’s about data. If you know where you came from, you can predict where you’re headed.

Audit your "Auto-Pilot" behaviors. The next time you snap at someone or handle a stressful situation, ask: "Is this me, or is this my dad?" Identifying which behaviors are inherited allows you to put a "buffer" between the impulse and the action.

Identify your biological baselines. If your family has a history of addiction or depression, acknowledge that your "tree" has those specific vulnerabilities. You can't change the wood you're made of, but you can choose where you plant yourself. Avoid high-risk environments if you know your genes are primed for struggle.

Celebrate the "Good Fruit." It’s easy to focus on the negative traits we inherit. But what about the resilience? The humor? The ability to cook a five-course meal out of leftovers? Lean into the strengths of your lineage.

Change the soil for the next generation. If you’re a parent, you are the tree. You can't change the seeds you're dropping, but you can change the environment they land in. Better "soil"—stability, love, education—ensures that even if the apple stays close, it grows into a healthier tree than the one before it.

The apple doesn't fall too far from the tree because, for the most part, we are comfortable in the shade of what we know. It takes a lot of energy to move. It takes a lot of courage to admit that while we are products of our past, we aren't prisoners of it.

The tree gives us our start. What happens once we hit the ground is a mix of gravity and the strength of our own roll. You can't choose your trunk, but you can certainly choose which way you grow.

Next Steps for Personal Growth:

Start by mapping out three specific traits you share with your parents—one positive, one neutral, and one you’d like to change. For the trait you want to change, identify the specific "trigger" that brings it out. By recognizing the pattern, you move from being a falling apple to a conscious individual capable of steering your own path.

Keep an eye on your reactions this week. See how many times you hear your mother's voice coming out of your mouth. It's usually more than you think. Acknowledge it, laugh at it, and then decide if that's the voice you want to use. That is how you master the legacy of the tree.