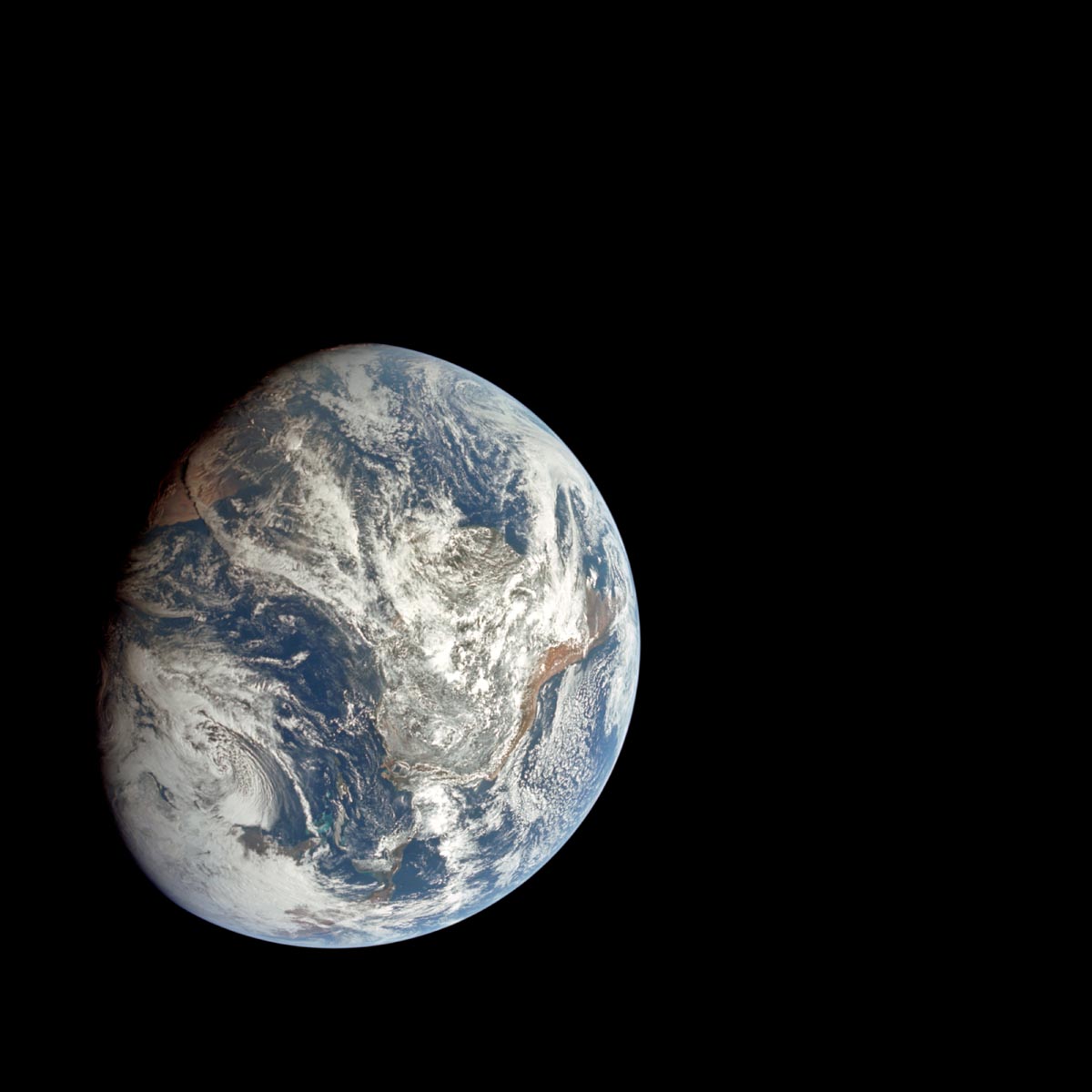

Frank Borman was annoyed. He was the commander of a cramped, vibrating tin can hurtling around the moon in December 1968, and he had a job to do. Keeping the three of them alive was priority one. Taking pretty pictures of the lunar surface for the geologists back in Houston was priority two. But then, during their fourth orbit, something unplanned happened. As the Command Module Columbia rotated, the blackness of space gave way to a sliver of blue. It wasn't the dead, cratered skin of the moon. It was Earth.

"Oh my God! Look at that picture over there!" Bill Anders shouted. You can hear the genuine, frantic shock in the mission audio. He wasn't supposed to be looking at Earth. They were there to scout landing sites for the future Apollo 11 crew. But there it was—a marble of sapphire and white swirled in a void so dark it looked like nothingness.

The Apollo 8 picture of Earth, eventually known as "Earthrise," wasn't actually a single photo. It was a chaotic scramble for color film. Anders asked Jim Lovell for a color roll. Lovell scrambled to find one. By the time they loaded the Hasselblad 500EL, they almost missed the shot. They caught it, though. And honestly, it changed the way we look at our own planet forever.

The snapshot that wasn't on the to-do list

NASA is famous for planning things down to the millisecond. They had flight manifests. They had checklists. They had specific coordinates for lunar craters. But nobody—not the flight directors, not the engineers, not the astronauts—truly anticipated the emotional gut-punch of seeing the Earth rise over the lunar horizon.

Technically, Earth doesn't "rise" if you're standing on the moon. Because the moon is tidally locked to us, the Earth stays in roughly the same spot in the lunar sky. It was only because the Apollo 8 capsule was in orbit, moving at high speeds, that the Earth appeared to crest over the horizon like a sun.

Anders grabbed the camera. He used a 250mm lens. He caught the contrast between the grey, sterile, "nasty" (as Borman called it) lunar desert and the vibrant, fragile home they’d left behind. It’s important to remember that in 1968, the world was a mess. The Vietnam War was screaming, Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy had been assassinated, and riots were tearing through cities. Then, on Christmas Eve, this photo arrived.

Why the orientation of the photo is actually a lie

If you look at the original Apollo 8 picture of Earth, the one Bill Anders actually snapped, the moon is on the right. The Earth is to the left. It looks "sideways" to our eyes.

👉 See also: Astronauts Stuck in Space: What Really Happens When the Return Flight Gets Cancelled

NASA flipped it.

They rotated the image 90 degrees so the lunar surface was at the bottom, creating a "horizon" that humans could instinctively understand. We need a ground. We need an "up." Without that rotation, the photo feels dizzying. By turning it, NASA turned a technical lunar orbit photograph into a landscape portrait of humanity's only home.

The technical wizardry behind the Hasselblad shot

We take high-definition photos for granted now. Your phone has more processing power than the entire Saturn V rocket. But back then, taking a photo in space was a massive gamble.

The camera was a modified Hasselblad 500EL. It didn't have a viewfinder in the traditional sense because the astronauts were wearing bulky helmets. They basically had to point and pray. The film was special, too—a thin-base Kodak Ektachrome that allowed for more exposures per roll.

- They used 70mm film, which is massive compared to the 35mm film your parents probably used.

- The shutter speed had to be fast because the spacecraft was hauling.

- There was no "auto" mode. Anders had to manually calculate the exposure for the Earth, which is significantly brighter than the dark lunar surface.

If he had exposed for the moon, the Earth would have been a white, blown-out blob. If he’d exposed for the blackness of space, everything would have been ruined. He nailed it.

What most people get wrong about Earthrise

A lot of people think this was the first photo of Earth from space. It wasn't. Not even close.

✨ Don't miss: EU DMA Enforcement News Today: Why the "Consent or Pay" Wars Are Just Getting Started

The ATS-3 satellite had taken color photos of the full Earth disk in 1967. Even the Lunar Orbiter 1 took a grainy, black-and-white photo of Earth from the vicinity of the moon in 1966. But those were robotic. They were cold. They were data.

The Apollo 8 picture of Earth mattered because it was a human perspective. It was three guys in a tiny room, 240,000 miles away, looking back and realizing they were looking at everyone who had ever lived. It wasn't a satellite map; it was a homecoming.

Galen Rowell, the famous nature photographer, called it "the most influential environmental photograph ever taken." And he’s right. Within two years of this photo being published, the first Earth Day was held. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was formed shortly after. Seeing the "Blue Marble" (though that name is technically reserved for the Apollo 17 shot) made the concept of a "limited" planet real. You could see the end of the atmosphere. It looked like a thin, blue shell on a hard-boiled egg.

The psychological impact: The Overview Effect

Psychologists and astronauts talk about something called the "Overview Effect." It’s a cognitive shift that happens when you see the Earth from orbit.

From out there, you don't see borders. You don't see the lines between the US and the USSR, which was a pretty big deal in 1968. You just see a closed system.

Jim Lovell later remarked that you could hide the entire Earth behind your thumb. Think about that. Every war, every masterpiece, every heartbreak, every billionaire, and every pauper—all of it hidden behind a single digit held at arm's length. It makes our problems look small. It makes the planet look like a life raft.

🔗 Read more: Apple Watch Digital Face: Why Your Screen Layout Is Probably Killing Your Battery (And How To Fix It)

How to find the high-res originals today

If you're looking for the real deal, don't just settle for a blurry JPEG from a Google Image search. NASA has digitized the original Apollo 8 rolls in stunning detail.

The specific frame you’re looking for is AS08-14-2383.

You can head over to the Arizona State University (ASU) Apollo Digital Image Archive. They have the raw scans. When you look at the raw version, you see the grain of the film. You see the slight imperfections. It feels more "real" than the cleaned-up, saturated versions used in documentaries.

Actionable steps for space enthusiasts

If you want to truly appreciate the Apollo 8 picture of Earth, don't just look at it on a screen.

- Download the TIFF files: Go to the NASA archives and download the uncompressed TIFF files. The level of detail in the cloud formations over the Atlantic is staggering.

- Check the flight transcripts: Read the "Apollo 8 Flight Journal" provided by NASA. Matching the dialogue to the exact moment the photo was taken adds a layer of tension you can't get from a history book.

- Visit the Smithsonian: If you're ever in D.C., the National Air and Space Museum holds the actual Hasselblad cameras used on these missions. Seeing the hardware makes the achievement feel much more physical and less like a CGI movie.

- Use the "Eyes on the Solar System" tool: NASA has a web-based 3D simulation where you can roll back the clock to December 1968 and see exactly where the spacecraft was positioned relative to the moon and Earth when Anders pressed the shutter.

The legacy of that Christmas Eve in 1968 isn't about the technology of the rocket. It’s about the fact that we went to the moon to explore it, and instead, we discovered the Earth. We saw ourselves for the first time.

That little blue ball is all we've got. The photo serves as a permanent reminder that in the vast, freezing vacuum of the cosmos, we are lucky to have a place that breathes.