Seventy-two days. Think about that for a second. That is longer than most summer vacations. It is longer than many relationships last. For the Andes Mountains plane crash survivors, seventy-two days was the distance between a routine flight to Santiago and a rescue that the world called a miracle, but they just called staying alive.

On October 13, 1972, Uruguayan Air Force Flight 571 clipped a ridge. It didn't just crash; it disintegrated. The wings ripped off. The fuselage slid down a glacier like a high-speed toboggan made of jagged aluminum and screaming passengers. Out of 45 people, many died instantly. Others died slowly. But sixteen walked out.

They weren't survival experts. They were rugby players. Just kids, basically. Nando Parrado and Roberto Canessa were in their early twenties. They didn't have North Face gear or satellite phones. They had loafers, blazers, and a desperate, gnawing hunger that eventually forced them to do the unthinkable. We talk about the cannibalism because it's sensational, but if you focus only on that, you miss the actual story of how humans function when everything—literally everything—is stripped away.

The moment the world stopped looking

Most people don't realize the search was called off after just eight days. The survivors actually heard this on a small transistor radio they managed to get working. Imagine that. You are freezing, you are bleeding, and you hear a voice on the radio say you're officially dead.

Parrado later wrote in his memoir, Miracle in the Andes, that hearing the news was actually a turning point. It sounds crazy, right? But he felt a weird sense of relief. The wait was over. No one was coming. If they wanted to live, they had to do it themselves. This is where the Andes Mountains plane crash survivors stopped being victims and started being a team.

They didn't have wood for fire. They were above the tree line. Everything was white and grey. They used the seat covers for blankets. They used pieces of aluminum to melt snow into drinking water because eating snow just lowers your core temperature and makes you more dehydrated. It was a brutal, daily grind of physics and biology.

💡 You might also like: Bootcut Pants for Men: Why the 70s Silhouette is Making a Massive Comeback

Why they did what they had to do

Let’s be real. When we talk about this story, the "anthropophagy" (the technical term for eating human flesh) is the elephant in the room. But for the survivors, it wasn't a dark ritual. It was a medical necessity.

Roberto Canessa was a medical student at the time. He was the one who had to explain it to the others. He looked at it through the lens of physiology. Your body needs protein to keep your heart beating. If you don't get it, your heart stops. Period.

They had long discussions about this. It wasn't an easy "yes." Some refused for days. They made a pact: if I die, you use my body so you can live. It was a gift of life, not a desecration. It’s easy to judge from a heated living room with a full fridge. It’s a lot harder when you’re staring at your own ribs poking through your skin at 11,000 feet.

The avalanche that nearly ended it all

Just when they thought things couldn't get worse, an avalanche hit the fuselage on October 29. It filled the cabin with snow in seconds. Eight more people died.

For three days, the remaining survivors were trapped in a tiny, airless pocket of snow inside the plane. They were literally buried alive. They had to poke a hole through the roof with a pole just to breathe. It’s hard to wrap your head around that kind of claustrophobia. They were sitting on the bodies of their friends who had just suffocated, waiting for the storm to stop.

📖 Related: Bondage and Being Tied Up: A Realistic Look at Safety, Psychology, and Why People Do It

The impossible trek of Parrado and Canessa

By December, they knew they were dying anyway. The snow was melting, but their bodies were failing. Nando Parrado, Roberto Canessa, and Vizintín decided to walk. They thought they were on the edge of the mountains. They weren't. They were right in the middle of the "Cordillera," the deepest part of the range.

Vizintín eventually went back to the plane so the other two could have his rations. Parrado and Canessa walked for ten days.

- They climbed a 15,000-foot peak with no climbing gear.

- They wore three pairs of jeans and several sweaters.

- They saw nothing but more mountains at the top.

Most people would have sat down and died right there. Parrado didn't. He looked at Canessa and said, "We may be walking to our deaths, but I would rather walk to meet my death than wait for it to come to me." That is the essence of the Andes Mountains plane crash survivors' spirit.

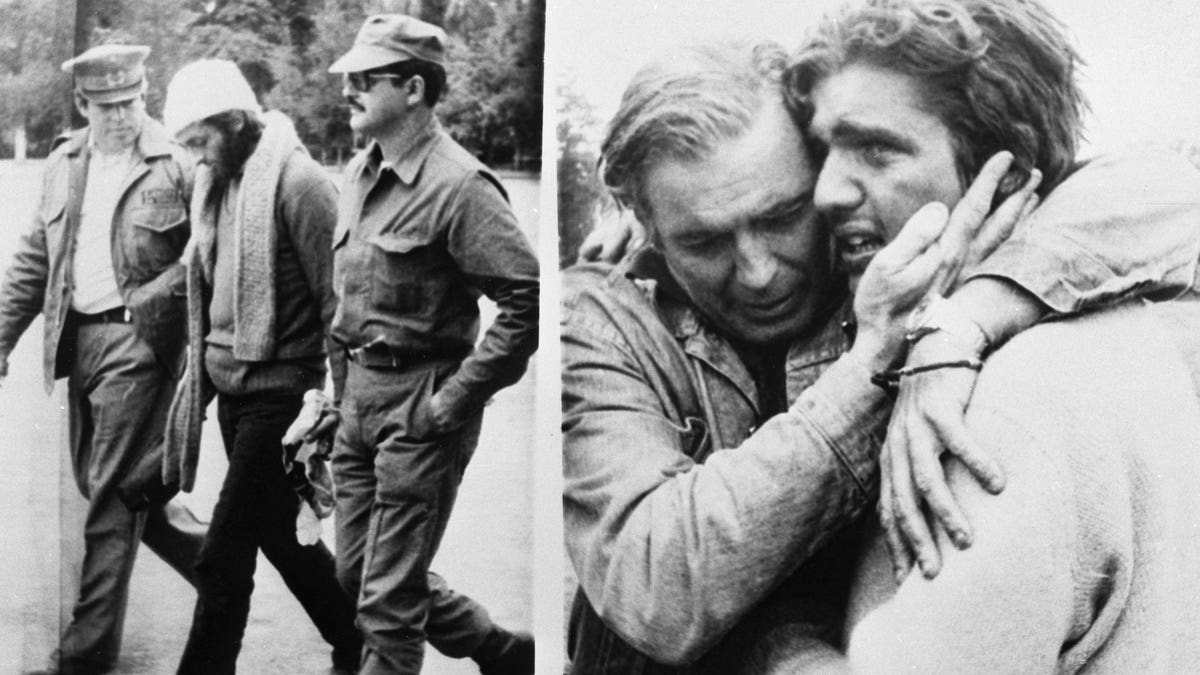

They eventually followed a river down. The air got thicker. They saw a cow. Then they saw a man on a horse across a river: Sergio Catalán. Since the river was too loud to talk across, Catalán threw a rock with a piece of paper and a pencil wrapped around it. Parrado wrote the note that changed history.

What we get wrong about the "Miracle"

Society loves a miracle. But if you talk to survivors like Gustavo Zerbino or Carlitos Páez, they’ll tell you it wasn't magic. It was work.

👉 See also: Blue Tabby Maine Coon: What Most People Get Wrong About This Striking Coat

They organized a society. One person was in charge of the water. Another in charge of the "meat." Another in charge of keeping the "bedroom" (the fuselage) clean. They kept a schedule. They told jokes. They prayed, sure, but they also argued and planned.

It’s also important to remember the families of those who didn't come back. For them, it wasn't a miracle. It was a tragedy. The survivors have spent 50 years balancing that guilt and that grief with the fact that they are alive.

Lessons from the heights

What can we actually take away from this? Honestly, most of us will never be in a plane crash. But everyone hits a "mountain" in their life.

- Accept the reality early. The survivors who thrived were the ones who stopped waiting for the rescue crews on day nine. The sooner you stop wishing things were different, the sooner you can deal with how things are.

- Small wins matter. Finding a way to melt snow wasn't "saving the day," but it bought them another 24 hours. Don't look at the whole mountain; look at the next ten feet.

- Community is survival. Not a single person who tried to go it alone survived. They lived because they leaned on each other, literally and figuratively.

The story of the Andes Mountains plane crash survivors isn't just a survival tale. It's a case study in human resilience. It shows that the "limit" of what a person can endure is much, much further than any of us think.

If you find yourself interested in the deep psychological aspects of this, check out the 2023 film Society of the Snow (La Sociedad de la Nieve) on Netflix. It’s widely considered by the survivors themselves to be the most accurate portrayal ever made—far more than the 1993 movie Alive. It captures the cold, the silence, and the specific, crushing weight of the Andes in a way that feels uncomfortably real.

To truly understand the logistics of their trek, you can look at the topographical maps of the "Glaciar de las Lágrimas." Seeing the actual distance Parrado and Canessa covered on foot, without oxygen or gear, makes the "miracle" label feel like an understatement. It was a feat of pure, stubborn human will.

Next Steps for Deep Research:

- Read Society of the Snow by Pablo Vierci, which features accounts from all 16 survivors.

- Visit the Museo Andes 1972 in Montevideo, Uruguay, if you ever travel to South America; it houses original artifacts and clothing from the crash site.

- Compare the survival strategies used here with the 1914 Shackleton expedition to see the parallels in leadership and resource management under extreme isolation.