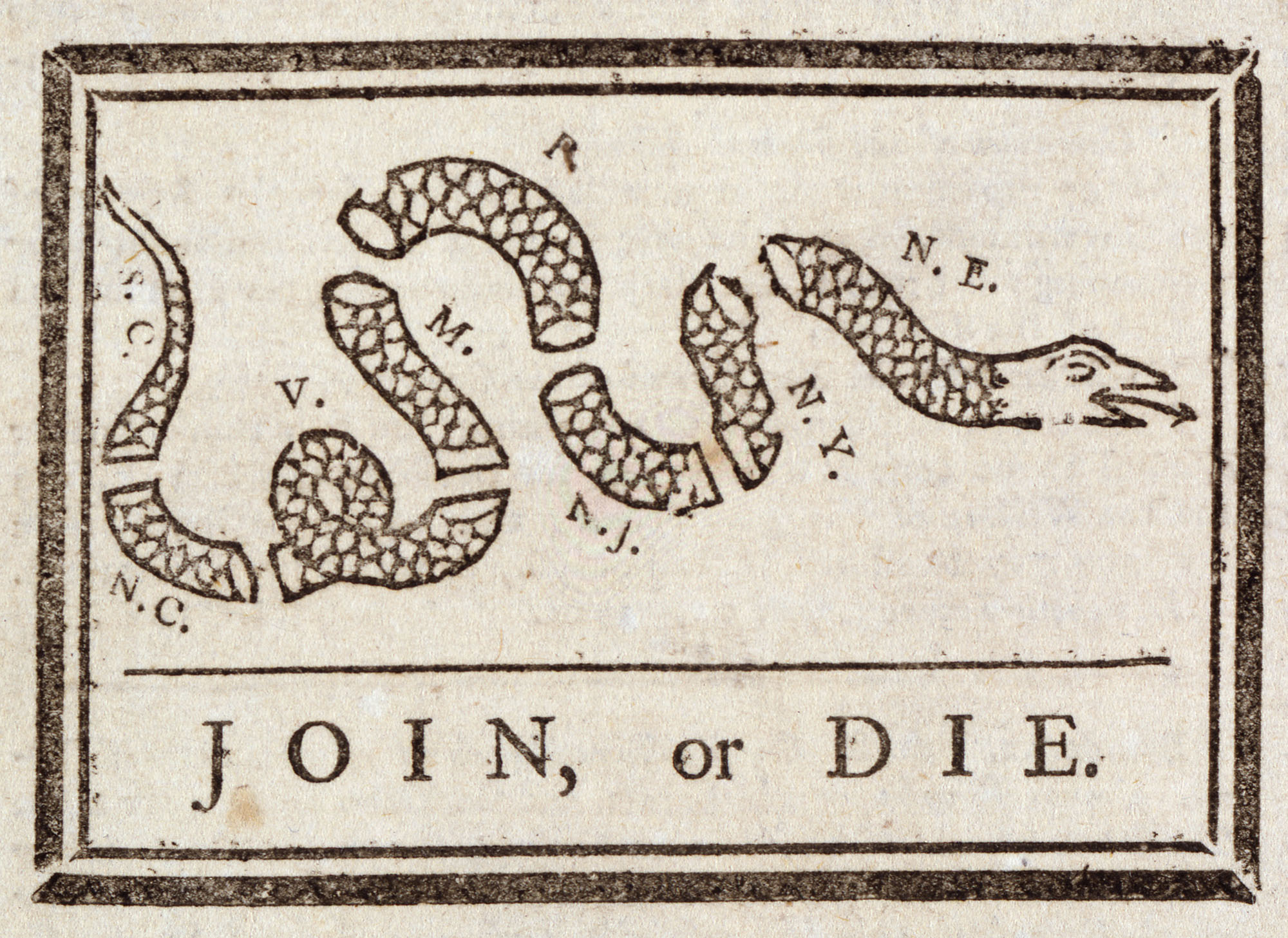

You’ve seen it. Even if you skipped every history lecture in high school, you know the image. It’s a snake. Cut into pieces. Eight of them, to be exact. Each segment is labeled with the initials of a British American colony. Beneath the severed reptile, the message is blunt: JOIN, or DIE.

Most people call it the first American political cartoon. Scholars often refer to it as the Albany Congress comic strip, though calling it a "strip" feels a bit modern for something printed via a woodblock in 1754. It wasn't just a doodle. Benjamin Franklin, the ultimate colonial polymath, used this stark imagery to argue for a unified colonial government during the Albany Congress.

It worked. Sorta. But not in the way Franklin originally intended.

The Brutal Reality Behind the Broken Snake

Franklin published this woodcut in the Pennsylvania Gazette on May 9, 1754. He didn't do it for "clout." He did it because the colonies were a mess. France and Great Britain were gearing up for what we now call the Seven Years' War (or the French and Indian War on this side of the pond). The borders were porous, the defense was disorganized, and the various colonial governments liked to bicker more than they liked to help each other.

Why a snake? It wasn't an arbitrary choice.

There was a common superstition back then—totally fake, obviously—that a snake cut into pieces could actually come back to life if the bits were put back together before sunset. Franklin was leaning hard into that folk myth. He was telling the colonies that they were currently dead weight. Disconnected. Useless. But, if they "joined" before the sun set on their opportunity to defend the frontier, they might just survive the coming onslaught.

The Albany Congress comic strip wasn't trying to start a revolution against the King. Not yet. In 1754, Franklin was a loyalist. He wanted the colonies to unite so they could be a better part of the British Empire. He wanted a "Plan of Union." The cartoon was a visual plea for a centralized colonial grand council that could handle Indian relations and military defense.

🔗 Read more: The Faces Leopard Eating Meme: Why People Still Love Watching Regret in Real Time

Why the Albany Congress Actually Failed

If you look at the history books, the Albany Congress is technically a failure.

Seven of the thirteen colonies sent representatives to Albany, New York, in the summer of 1754. They met with the Iroquois Confederacy (the Haudenosaunee) to shore up alliances. Franklin presented his "Albany Plan," which was remarkably forward-thinking. It proposed a President-General appointed by the Crown and a Grand Council chosen by the colonial assemblies.

The delegates in the room actually liked it. They approved it! But then it went back to the individual colonial assemblies for ratification.

Every single one of them rejected it.

The colonies were terrified of losing their own power to a central authority. They didn't want to pay taxes to a council they couldn't control. Ironically, the British Board of Trade also hated the plan because they thought it gave the colonies too much independence. Franklin's snake stayed in pieces.

The Second Life of the Join or Die Imagery

Here is where the Albany Congress comic strip gets weirdly meta. Fast forward twenty years. It’s 1774. The vibes have shifted. Now, the colonies aren't worried about the French; they're furious at the British.

💡 You might also like: Whos Winning The Election Rn Polls: The January 2026 Reality Check

Paul Revere and other revolutionary printers dug up Franklin’s old snake. They dusted it off and changed the context entirely. Suddenly, the snake wasn't about colonial defense under the British flag—it was about rebellion against it.

You started seeing the snake everywhere. It appeared in the masthead of the Massachusetts Spy. It was the literal backbone of the Gadsden flag ("Don't Tread on Me"). By the time the Revolutionary War actually kicked off, that 1754 woodcut had become the universal symbol of American identity. Franklin, the guy who just wanted a more efficient way to manage frontier forts, had accidentally created the branding for a new nation.

Why the "Strip" Format Mattered for SEO in 1754

Okay, they didn't have Google in the 18th century. But Franklin was an expert at "content distribution."

He knew that literacy rates were hit-or-miss. Not everyone was going to read a 2,000-word editorial about the complexities of colonial taxation and Iroquois diplomacy. But everyone could understand a picture of a dead snake.

It was the original viral content.

Other newspapers across the colonies—from New York to South Carolina—copied the image. They didn't ask for permission. They just carved their own woodblocks and ran it. This "organic sharing" is exactly why we still study the Albany Congress comic strip today. It bypassed the intellectual elite and spoke directly to the common person in the tavern.

📖 Related: Who Has Trump Pardoned So Far: What Really Happened with the 47th President's List

Misconceptions You Probably Believe

- Myth 1: It was about the Revolution. Nope. As we established, it was originally a pro-British defense ad.

- Myth 2: The snake represents the 13 colonies. Check the initials again. There are only eight segments. Franklin grouped the New England colonies (New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut) into one piece labeled "N.E." Georgia was left off entirely because it was considered too "frontier" and distant at the time.

- Myth 3: Franklin drew it himself. This is debated. While he almost certainly came up with the concept and likely carved the original woodblock, he was a busy guy. Some historians think an apprentice might have done the heavy lifting, though Franklin gets the credit as the "author."

How to Apply These Lessons Today

If you’re looking for a takeaway from a 270-year-old cartoon, it’s about the power of the "Simplified Visual."

In a world of noise, the clearest signal wins. Franklin didn't use metaphors about lions or eagles. He used a local pest—the rattlesnake—that everyone recognized and feared. He took a complex political problem (lack of centralized infrastructure) and turned it into a binary choice: Join or Die.

There’s no middle ground in that headline.

To truly understand the impact of the Albany Congress comic strip, you have to look at it as a piece of psychological warfare. It was designed to make the reader feel "incomplete" if they weren't part of the collective. It’s a masterclass in identity politics that predates the United States itself.

Next Steps for History Buffs and Communicators

- Visit the Original: If you’re ever in Philadelphia, the Historical Society of Pennsylvania holds original copies of the Pennsylvania Gazette. Seeing the actual ink on the rag paper changes your perspective on how small and tactile this "viral" moment actually was.

- Analyze the Segments: Look closely at a high-res scan of the cartoon. Notice the order: South Carolina is the tail, New England is the head. Franklin was making a subtle point about the hierarchy and geography of the colonies.

- Study the Gadsden Evolution: Track how the "segmented" snake of 1754 evolved into the "coiled" snake of 1775. It represents the shift from a broken, defensive posture to a unified, aggressive one.

- Simplify Your Own Message: If you’re struggling to explain a complex idea, try the "Franklin Test." Can you represent your entire argument in a single, primitive image with three words or less? If not, you haven't simplified it enough.