You’ve probably seen the grainy stills or the controversial posters on a cinephile’s Instagram feed. Or maybe you just heard about the James Mason connection. Honestly, talking about the Age of Consent movie feels like stepping into a time machine that’s slightly broken. Released in 1969, this Michael Powell film wasn't just another beachy romp from the late sixties. It was a career-defining moment for Helen Mirren, a swan song for a legendary director, and a massive headache for censors who didn't know what to do with a film that felt both high-art and totally scandalous.

It’s weird.

People often confuse the actual plot with the provocative title. If you’re looking for a gritty legal drama or a lecture on the ethics of the late 60s, you’re in the wrong place. This is a story about a burnt-out artist named Bradley Morahan (played by Mason) who escapes the soul-crushing New York art scene to find his muse on the Great Barrier Reef. There, he meets Cora Ryan, a wild, barefoot girl played by a then-unknown Mirren.

The Michael Powell Connection

To understand why this movie exists, you have to look at Michael Powell. This guy was a titan of British cinema. We're talking about the man behind The Red Shoes and Black Narcissus. But by 1969, he was basically persona non grata in the UK film industry because of Peeping Tom. That movie destroyed his reputation.

He went to Australia to find redemption.

He didn't find a blockbuster, but he found something that aged in a really fascinating way. Powell wasn't trying to make a "dirty movie," even though that's how some distributors marketed it. He was obsessed with the idea of the "primitive" versus the "civilized." The Age of Consent movie was his attempt to capture that friction. It’s colorful. It’s bright. It’s filled with scenes of the Australian coast that make you want to book a flight immediately. But under that sun-drenched surface, there’s a tension that makes modern audiences squirm.

Why the title causes so much confusion

Let’s get real about the name. Age of Consent sounds like a warning or a legal document. In reality, it was based on a 1938 semi-autobiographical novel by Norman Lindsay. Lindsay was a bit of a provocateur himself—an Australian artist who spent his life fighting against the "wowser" culture (basically, the fun-police of his era).

The title refers to the legal age of marriage and sexual autonomy, which, in the context of the story, is more of a thematic backdrop than a courtroom plot point. Cora is a minor in the eyes of the law during the story’s setting, yet she is the one who initiates much of the interaction with the much older Bradley. She isn't a victim in the traditional cinematic sense; she’s a force of nature. This inversion is exactly what makes the film so difficult to categorize. It’s not quite a romance, not quite a drama, and definitely not a comedy, though it tries to be funny sometimes with a subplot involving a mooching friend played by Jack MacGowran.

💡 You might also like: Why Love Island Season 7 Episode 23 Still Feels Like a Fever Dream

Helen Mirren’s raw debut

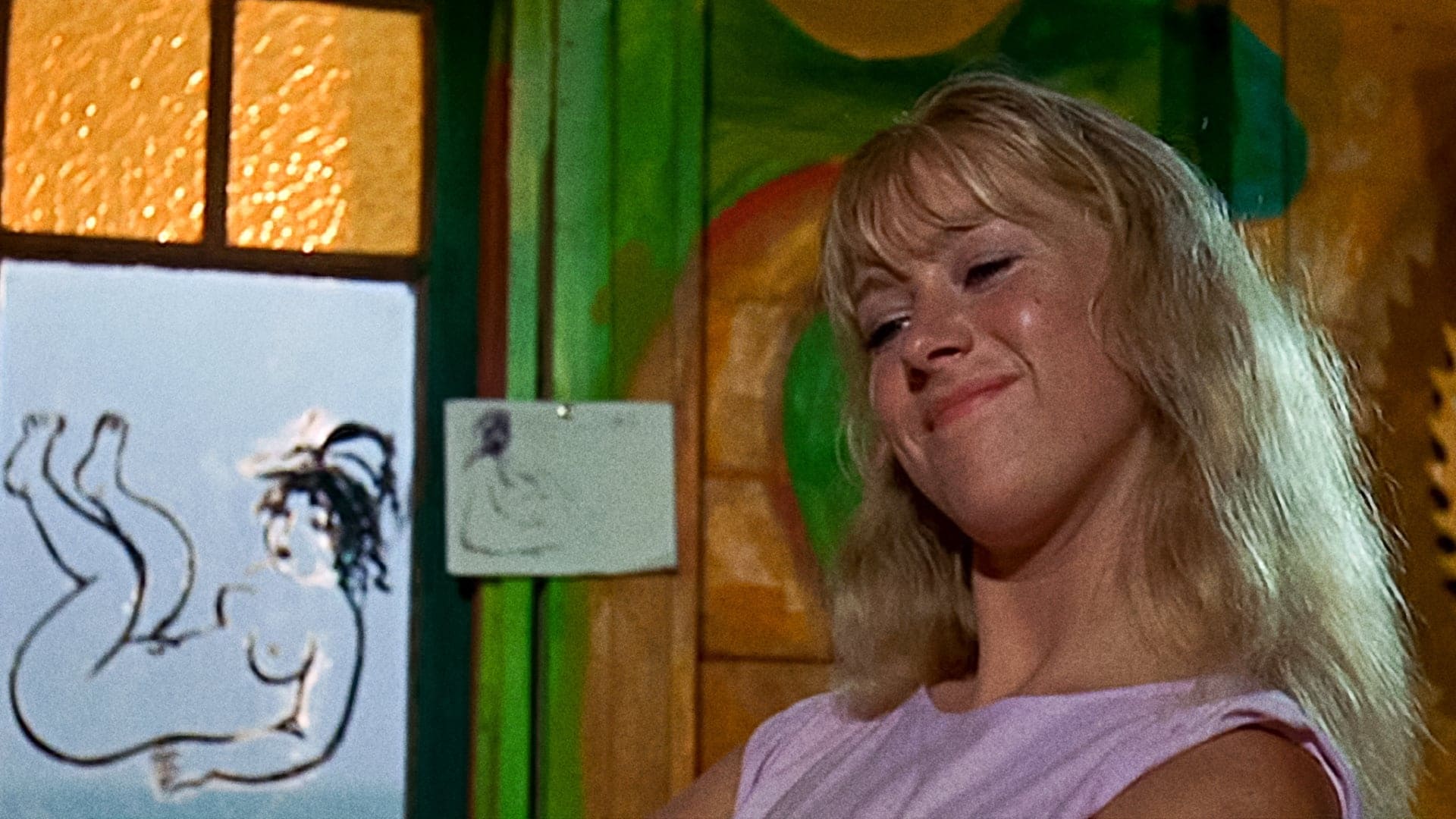

If you watch this today, you’re likely watching it because of Helen Mirren. It was her first major film role. She was 22, playing younger, and she was fearless.

Actually, "fearless" is an understatement.

She spends a massive chunk of the movie either nude or nearly nude. In 1969, this was a huge deal. It wasn't just about nudity for the sake of titillation—though the studio certainly used it to sell tickets—it was about the character's total lack of shame. Cora is connected to the island. She’s part of the landscape. Mirren brings this earthy, unpolished energy that makes James Mason’s character look like a stiff, dusty relic.

Mason, for his part, plays the "tortured artist" with a surprising amount of restraint. He was one of the producers, and he really believed in the project. He saw it as a sophisticated look at how inspiration is sparked. But critics at the time? They weren't all convinced. Some saw it as a dirty old man’s fantasy. Others saw it as a masterpiece of the "New Wave" style hitting the Australian shores.

The "Lost" Version and the Restoration

For years, people who saw the Age of Consent movie in the US or UK saw a butchered version. The censors had a field day. They cut out roughly 11 minutes of footage, mostly focusing on Mirren’s nude scenes and some of the more "suggestive" dialogue. They even replaced the original score by Peter Sculthorpe with something more "conventional" and boring.

It stayed that way for decades.

It wasn't until around 2005 that the film was properly restored. The Film Foundation, which is Martin Scorsese’s baby, stepped in. Scorsese has always been a massive Michael Powell fanboy (he eventually married Powell’s editor, Thelma Schoonmaker). Thanks to their work, we can now see the movie as Powell intended—scary, beautiful, and weirdly innocent in its own provocative way. The restored version restored the Sculthorpe score, which uses these strange, evocative sounds that perfectly match the Great Barrier Reef setting.

📖 Related: When Was Kai Cenat Born? What You Didn't Know About His Early Life

The Ethics of the "Muse"

In 2026, our lens on these themes has changed radically. We talk about power dynamics constantly. We talk about the "male gaze." When you watch an older man painting a young woman on a secluded island, the alarms go off.

That’s fine. It should probably feel a bit uncomfortable.

But the movie complicates the narrative. Cora isn't just a passive object. She’s transactional. She wants money so she can buy a boat and escape her alcoholic grandmother. She sees Bradley as a ticket out of her miserable life. He sees her as a way to fix his artistic block. It’s a messy, mutually exploitative relationship that doesn't fit into a neat "good" or "bad" box.

Why it’s still relevant for film buffs

If you’re interested in the history of Australian cinema, you can’t skip this. It was part of the "Australian New Wave" before that term even really existed. It captured a version of the outback and the coast that wasn't just "Crocodile Dundee" stereotypes. It was lush and dangerous.

Also, the cinematography by Hannes Staudinger is incredible. They used underwater cameras in ways that were pretty revolutionary for the time. When you see Cora diving for shells, it doesn't look like a studio tank. It looks like the actual, terrifyingly beautiful ocean.

What most people get wrong

The biggest misconception is that this is a "sleaze" film. Because of the title and the nudity, it gets lumped in with the "sexploitation" era of the late 60s and early 70s. But Michael Powell was a poet. Even when he was making something controversial, he was focused on the light, the color, and the emotional resonance of the scene.

Is it a masterpiece? Maybe not on the level of The Red Shoes. But it’s a vital piece of film history. It shows a legendary director trying to find his voice again in a world that had changed since his heyday in the 1940s. It shows a future Oscar winner (Mirren) proving she was a star from day one. And it shows how film titles can often overshadow the actual art they represent.

👉 See also: Anjelica Huston in The Addams Family: What You Didn't Know About Morticia

Critical reception then vs. now

When it premiered in Australia, it was a hit. People loved seeing their landscape on the big screen. When it hit the UK, the critics were much harsher. They couldn't forgive Powell for his past "sins" with Peeping Tom. They called it indulgent.

Today, the conversation is more about the legacy of the performers. We look at James Mason’s career—from Lolita to this—and see a pattern of him playing men fascinated by youth. It’s a recurring theme in his filmography that adds a layer of meta-commentary to the whole experience.

Practical takeaways for viewers

If you're going to watch the Age of Consent movie, here is how to actually enjoy it:

- Find the Restoration: Seriously, don't watch a grainy YouTube rip of the censored version. The 2005 restoration is the only way to see the colors as they were meant to be.

- Context is Everything: Remember this was filmed at the height of the sexual revolution. The "shock value" was intentional, but it was also a product of its time.

- Watch for the Editing: Powell’s influence is all over the pacing. It’s slower than modern movies, but it lingers on the right things.

- Research Norman Lindsay: If you really want to go down the rabbit hole, look up the artist the book was based on. His house in Springwood is now a museum, and it’s just as eccentric as the movie suggests.

The film serves as a bridge between the Golden Age of British cinema and the raw, uninhibited style of the 70s. It’s a weird, sunny, uncomfortable little movie that refuses to be forgotten.

How to access the film today

You can usually find the restored version on boutique Blu-ray labels like Indicator or through specialized streaming services like the Criterion Channel. It’s rarely on the "big" platforms like Netflix because, let’s be honest, it’s a bit too niche for the algorithm.

If you're a fan of Helen Mirren, it's essential viewing just to see where she started. You can see the DNA of her later roles in the way she carries herself—bold, slightly defiant, and completely in control of the screen.

To wrap your head around the film's legacy, look for the documentary The Burning Glass, which covers Michael Powell’s later years. It provides the necessary background on why he felt the need to go to the literal ends of the earth (Australia) to keep making movies. Understanding his exile makes the isolation of the characters in the film feel much more personal. Focus on the interplay between the environment and the characters; the island is just as much a protagonist as Bradley or Cora.