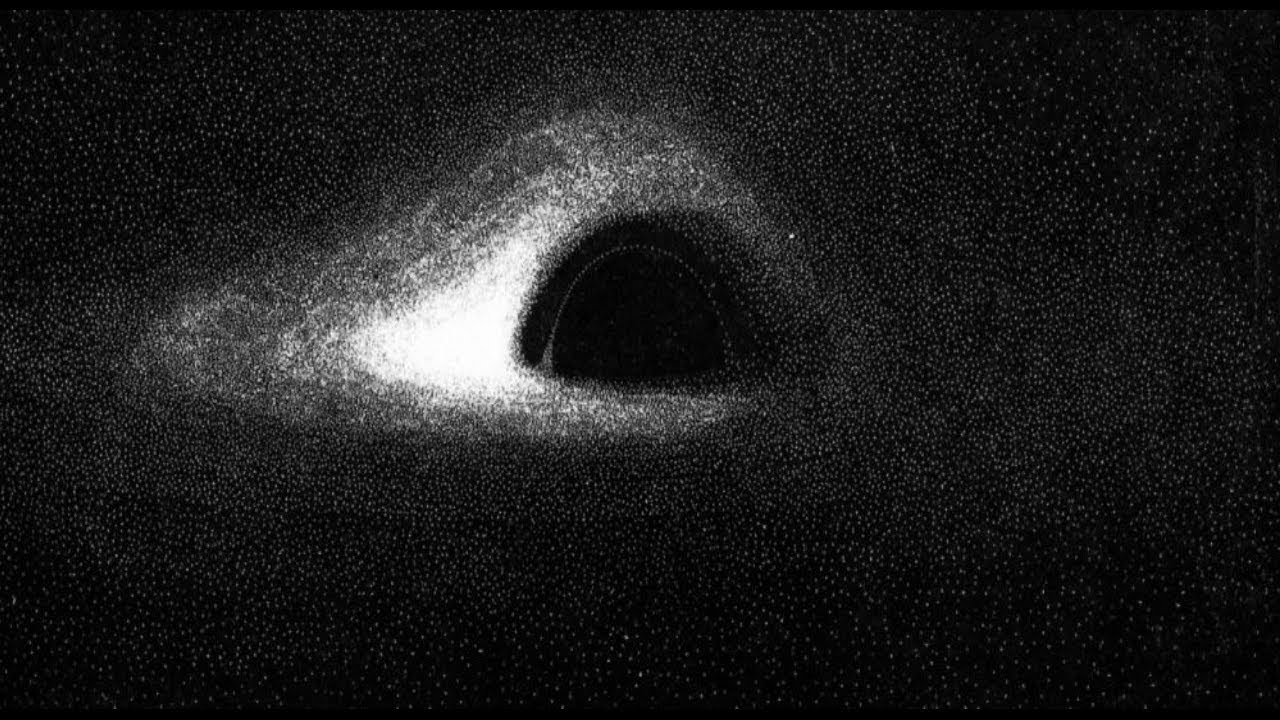

It looks like a fuzzy orange donut. Honestly, that’s the first thing most people thought back in 2019 when the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) team dropped the first actual photo of a black hole on a world that had been raised on Interstellar and high-budget CGI. We expected high-definition, swirling vortexes of crystalline light. Instead, we got a blurry, glowing ring. But here is the thing: that blur is arguably the most significant achievement in the history of observational astronomy. It’s not just a picture. It’s a confirmation that Albert Einstein was right about how the universe breaks at its edges.

You’re looking at M87*. It’s a supermassive monster sitting in the center of the Messier 87 galaxy, about 55 million light-years away. To get that image, scientists had to turn the entire Earth into a single telescope. They didn’t just point a lens at the sky and click a shutter. They synchronized atomic clocks across the globe, from the South Pole to the Spanish Sierra Nevada, to capture radio waves that had been traveling through the void for millions of years.

The Physics of the "Shadow"

A black hole is, by definition, invisible. Light cannot escape it. So, when we talk about an actual photo of a black hole, we aren't seeing the hole itself. We are seeing the "shadow."

Gravity there is so intense that it bends light into a circle. The bright ring you see in the image is the accretion disk—gas and dust spinning at nearly the speed of light, rubbing together, and getting so hot they glow in radio frequencies. The dark patch in the middle? That’s the event horizon’s shadow. If you fell into that darkness, you’d never come back. Physics as we know it would simply stop applying to you. It’s a one-way door to nowhere.

Why was it so blurry?

Pixels. Or rather, a lack of them.

📖 Related: Installing a Push Button Start Kit: What You Need to Know Before Tearing Your Dash Apart

Think about trying to photograph an orange on the surface of the Moon from your backyard. That’s the level of magnification we are talking about. To get a "clear" photo of M87*, you would need a telescope the size of the Earth. Since we can't build a glass mirror that big without the planet collapsing, the EHT team used a technique called Very Long Baseline Interferometry (VLBI). They used eight different telescopes to act as one.

The gaps between the telescopes had to be filled in by algorithms. Dr. Katie Bouman and a massive team of researchers developed the imaging processing that stitched these fragments together. It wasn't "faked." It was reconstructed. The blurriness is just the limit of our current technology, but even that blur contains specific data points about the black hole's mass and spin that matched Einstein’s General Relativity equations to a terrifying degree of accuracy.

Sagittarius A* vs. M87*

Three years after the M87* reveal, we got a second actual photo of a black hole, and this one was "ours." Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*) lives right in the middle of the Milky Way.

Surprisingly, it looks almost exactly like the first one. This was actually a relief for scientists. It proved that whether a black hole is a few million times the mass of our sun (like Sgr A*) or billions of times the mass (like M87*), the physics remains consistent.

👉 See also: Maya How to Mirror: What Most People Get Wrong

- M87*: This thing is a beast. It’s 6.5 billion times the mass of the Sun. Because it's so big, the gas takes days or weeks to orbit it. This made it "easier" to photograph because it stayed still for the camera.

- Sgr A*: This one is much smaller, only about 4 million solar masses. The gas orbits it in minutes. Imagine trying to take a long-exposure photo of a puppy that won't stop chasing its tail. That’s why the Sgr A* image was actually harder to produce than the M87* one.

The 2023 Sharpening: AI Steps In

In 2023, researchers used a new machine-learning technique called PRIMO to "sharpen" the original M87* image. They fed the algorithm thousands of simulations of black holes to help it understand what the "gaps" in the data likely looked like. The result? A much thinner, tighter ring of light.

Some purists argue this isn't an "actual photo" anymore, but a model. But in radio astronomy, the line between "data" and "image" has always been thin. We don't see radio waves with our eyes. Every image of space you've ever seen, from Hubble to James Webb, is a translation of data into colors and shapes we can understand.

What Most People Get Wrong

One common myth is that the black hole is "sucking" things in like a vacuum cleaner. It’s not. If you replaced our Sun with a black hole of the exact same mass, Earth wouldn't get sucked in. We’d just keep orbiting it in the dark. You have to get very close—past the innermost stable circular orbit (ISCO)—before you’re doomed.

Another misconception: the orange color. The actual photo of a black hole isn't orange. The telescopes captured radio waves, which are invisible to the human eye. Scientists chose orange and yellow to represent the intensity of the radiation. It could have been purple or green, but orange feels "hot," and the accretion disk is definitely hot.

✨ Don't miss: Why the iPhone 7 Red iPhone 7 Special Edition Still Hits Different Today

How to Follow Future Discoveries

We are currently in a golden age of gravitational physics. The EHT is adding more telescopes, including some in space, to get higher-resolution images. We might eventually see "movies" of a black hole, watching the plasma swirl around the event horizon in real-time.

Practical Steps for Space Enthusiasts:

- Track the EHT Updates: The official Event Horizon Telescope website (eventhorizontelescope.org) is where the raw data and peer-reviewed papers actually live.

- Use NASA’s Eyes: Download the "NASA's Eyes" app. It lets you visualize where these objects are in relation to our galaxy in a 3D environment.

- Check the ArXiv: If you want the real, unvarnished math, search "black hole imaging" on arXiv.org. It’s where researchers post their papers before they even hit the journals.

- Look at Gravitational Waves: Keep an eye on LIGO (Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory). They don't take "photos," but they "hear" black holes colliding, which provides a completely different kind of "image" of how these objects behave.

The blurry donut was just the beginning. We’ve finally looked into the abyss, and for the first time, the abyss looked back.