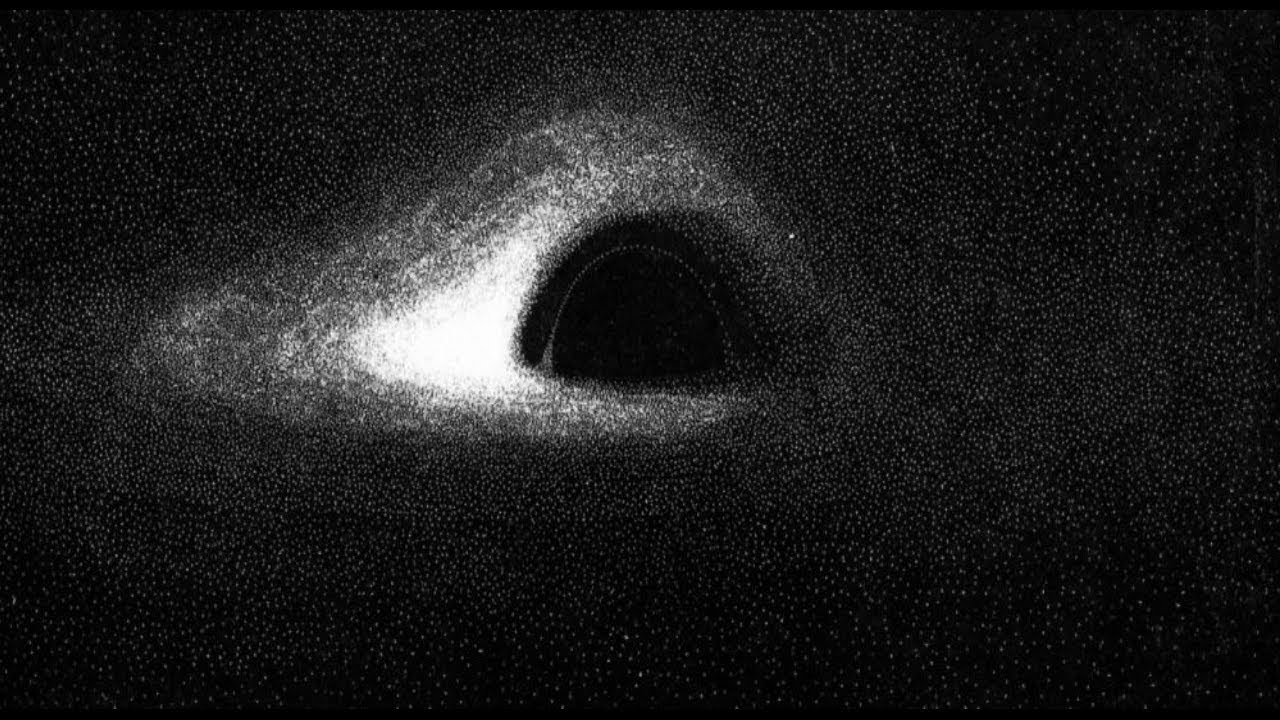

We all saw it. That fuzzy, glowing orange ring floating in a sea of absolute nothingness. It was April 10, 2019, and the world stopped for a second to look at a photo that technically shouldn't exist. Before that moment, every picture you’d ever seen of a black hole was a painting. An illustration. A CGI render from Interstellar. But the actual image of black hole M87* changed the game. It proved that Einstein wasn't just guessing—he was right.

It’s easy to look at that photo and think, "Is that it?" Honestly, it’s a bit blurry. Compared to the crisp 4K images we get from the James Webb Space Telescope, the M87* shot looks like it was taken with a potato. But that "potato" was actually a planet-sized virtual telescope. Taking that photo was basically like trying to photograph a mustard seed in Washington, D.C., from a sidewalk in Berlin.

The scale is just stupid.

The truth about the actual image of black hole M87*

Let's get one thing straight: you aren't seeing the black hole itself. You can’t. Light can’t escape it, so there’s nothing to see. What you’re looking at in the actual image of black hole is the "shadow." It’s the silhouette of the event horizon against the glowing mess of superheated gas swirling around it. This gas is moving at nearly the speed of light. It gets so hot that it glows in radio waves, which is what the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) actually captured.

The EHT isn't one big dish. It's a network. Scientists linked up eight different radio observatories across the globe—from the South Pole to the volcanoes of Hawaii and the Spanish Sierra Nevada. By using a technique called Very Long Baseline Interferometry (VLBI), they turned Earth into one giant lens.

They had so much data that they couldn't send it over the internet. It was petabytes of information. They literally had to fly physical hard drives from the South Pole on planes because it was faster than any fiber-optic cable on the planet. Think about that for a second. We had to wait for the ice to melt in Antarctica just to get the data out so we could start processing the image.

Why is it orange?

Nature isn't orange. Not out there, anyway. The "color" in the photo is totally a choice. Radio waves are invisible to our eyes. To make the data understandable, the EHT team mapped the intensity of the radio signals to a color scale. They chose orange and yellow because it looks hot and bright. It represents the intensity of the radiation. If they wanted to, they could have made it neon purple or slime green, but orange feels right for a cosmic furnace.

Sagittarius A*: The one in our own backyard

People often confuse the first image with the second one. In 2022, we got another gift: the actual image of black hole at the center of our own galaxy, Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*). This one was way harder to get. Even though it's closer to us than M87*, it’s also much smaller.

Imagine trying to take a long-exposure photo of a toddler who won't stop running. That was Sgr A*. While M87* is a massive, slow-moving beast that takes days or weeks to change its appearance, Sgr A* changes in minutes. The gas swirls around it so fast that the image was constantly shifting while the telescopes were trying to watch it.

Katie Bouman and the rest of the EHT team had to develop insane algorithms to "average out" the movement. They basically had to reconstruct a clear picture from a shaky video. When you look at the Sgr A* image, you see three bright spots. Scientists think those are just artifacts of how the data was processed or perhaps temporary "hot spots" in the disk. It’s messy. It’s real.

The donut shape is non-negotiable

Why a ring? Why not a sphere? This is where gravity gets weird. The black hole is a sphere, but the light is being bent by gravity. This is called gravitational lensing. The light coming from behind the black hole gets bent around it and sent toward us. No matter which way you look at a black hole, you’ll always see a ring. It’s like a cosmic hall of mirrors.

👉 See also: TV Wall Mounts 75 Inch: What Most People Get Wrong Before Drilling

If the ring was perfectly symmetrical, it would mean we’re looking at it perfectly head-on. But in the actual image of black hole M87*, one side is brighter. That’s the Doppler effect. The gas on the bottom of the image is moving toward us, which makes it appear brighter. The stuff on top is moving away. It’s the same reason a police siren changes pitch as it drives past you, just with light instead of sound.

Machines, math, and the human element

The EHT team didn't just press a button. They spent years cleaning the data. They were terrified of "seeing" what they expected to see. To avoid bias, they split into four different teams. Each team worked in total isolation, using different methods to reconstruct the image. If all four teams came up with a donut, then the donut was real.

They did.

One team used "traditional" methods. Another used machine learning. They even tested their algorithms on "fake" data—like pictures of the Golden Gate Bridge or a literal glazed donut—to make sure the software wasn't just forcing everything into a circle. The fact that the actual image of black hole emerged consistently across all groups is why we can trust it.

What's next for black hole photography?

We aren't done. The EHT is adding more telescopes. More dishes mean more "pixels" in our virtual camera.

✨ Don't miss: Why It’s So Hard to Ban Female Hate Subs Once and for All

Soon, we might see the first movies. Not just a still frame, but a flickering, moving video of a black hole consuming matter in real-time. Scientists are also looking at the "photon ring," which is a much thinner, sharper circle of light even closer to the event horizon. Capturing that would be the ultimate test of General Relativity.

There's also talk of putting radio telescopes in space. If we can get a satellite into a high orbit, we can create a virtual telescope larger than Earth. That would give us the resolution to see black holes in other galaxies, or even see the "jet" of M87* in much higher detail.

Actionable insights for the curious mind

If you want to dive deeper than just looking at the pretty orange ring, here is what you should actually do.

- Check the source data: The Event Horizon Telescope collaboration publishes their papers as Open Access. You don't need a university login to read them. Look for the "First M87 Event Horizon Telescope Results" papers. They are dense, but the introductions are surprisingly readable.

- Watch the documentaries: Black Holes: The Edge of All We Know is a fantastic look at the human struggle behind these images. It shows the tension and the math, not just the finished product.

- Explore the simulations: Compare the actual image of black hole with the simulations produced by the Veritasium team or NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. Seeing the "perfect" math-based model next to the "blurry" real-life photo helps you understand exactly what the telescopes were struggling to see.

- Keep up with the EHT updates: They are currently working on the next-generation EHT (ngEHT). This project aims to bring us color-coded videos and sharper images by 2030.

The most important thing to remember is that these images aren't just photos. They are trophies. They represent the moment humanity finally reached out and touched the most extreme environment in the universe. We used the entire planet as a tool, and for once, we all looked at the same thing at the same time and just wondered.