Soil isn't just dirt. If you’re a civil engineer or a contractor staring at a muddy pit, you know that. You’ve probably looked at an AASHTO soil classification chart a thousand times, maybe even memorized the A-1 to A-7 categories during a late-night study session for the PE exam. But why do we still use a system created in the late 1920s to build billion-dollar highways today?

Honestly, it's because the system works where it matters most: under the tires. While the Unified Soil Classification System (USCS) is great for foundations and dams, AASHTO—developed by the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials—was built specifically for roads. It tells you exactly how a material is going to behave as a subgrade. It’s practical. It’s gritty.

💡 You might also like: AirPods Max New Release: Why the 2024 Refresh Left So Much Out

If you get the classification wrong, the road fails. It’s that simple.

The Logic Behind the A-Groups

The AASHTO system isn't random. It’s a hierarchy of performance. Basically, the system sorts soil based on its suitability for highway construction, moving from the best (A-1) to the worst (A-7). If you’ve got A-1-a soil, you’ve basically struck gold in the construction world. It’s stable, drains well, and doesn’t heave when the temperature drops.

But life is rarely that easy. Most of the time, you’re dealing with the messy middle.

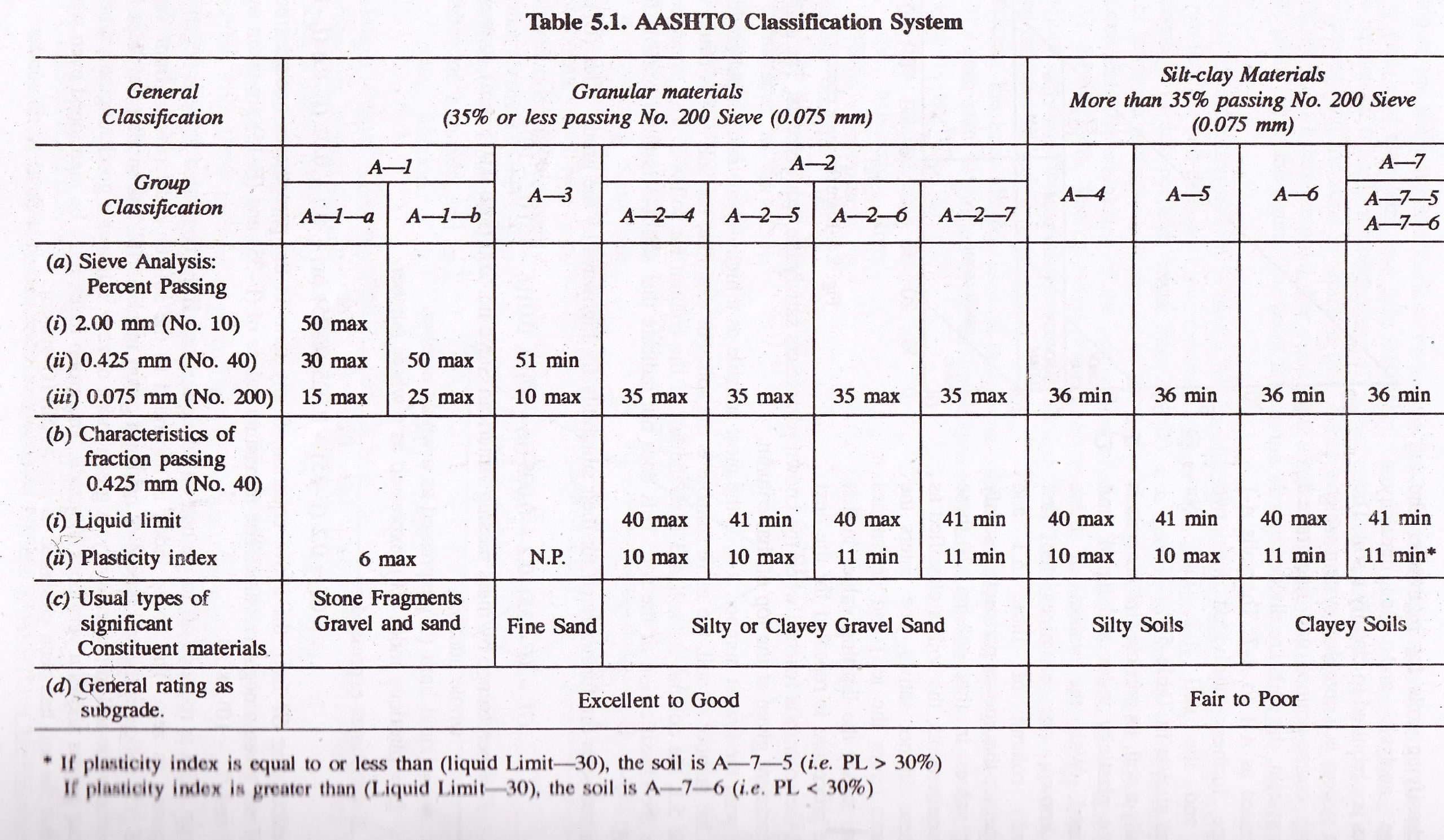

The chart splits everything into two main categories: granular materials and silt-clay materials. The dividing line is the Number 200 sieve. If 35% or less of your sample passes through that tiny mesh, you’re looking at granular material. If it’s more than 35%, you’re in the world of silts and clays. This "35% rule" is the fundamental fork in the road for any highway lab technician.

Granular Materials (The Good Stuff)

Group A-1 consists of well-graded mixtures of stone fragments, gravel, and sand. Think of these as the backbone of a high-speed interstate. Within this group, A-1-a and A-1-b are distinguished by how much coarse sand versus gravel they contain.

Then you have A-3. It’s weird. Why is A-3 before A-2? Because A-3 is fine sand—think beach sand or desert blow sand. It’s actually better than many A-2 soils because it’s non-plastic and drains beautifully, even if it’s a pain to compact.

A-2 is the "catch-all" group. These are silty or clayey gravels and sands. They are okay, but they start to hold moisture. When a contractor sees A-2-6 or A-2-7 on a lab report, they know they might have some stability issues once the rainy season hits.

Why the Group Index (GI) Is Your Real Best Friend

The AASHTO soil classification chart isn't complete without the Group Index. Classification gets you in the ballpark, but the GI tells you exactly how crappy the soil really is.

The formula looks like a nightmare of parentheses:

$$GI = (F - 35)[0.2 + 0.005(LL - 40)] + 0.01(F - 15)(PI - 10)$$

Where $F$ is the percentage passing the No. 200 sieve, $LL$ is the Liquid Limit, and $PI$ is the Plasticity Index.

You don't need to do the math by hand these days, but you should understand what it's saying. A Group Index of 0 means you’ve got "good" subgrade. If that number starts climbing toward 20 or higher, you’re looking at "very poor" material. The GI essentially "penalizes" the soil for having too many fines, too high a liquid limit, or too much plasticity.

I remember a project in East Texas where the initial classification was A-7-6. On paper, it’s just a clay. But once we calculated a GI of 32, the engineers realized they couldn’t just compact it and call it a day. They had to bring in lime stabilization because that soil was basically grease when wet.

Silt-Clay Materials and the A-7 Trap

When you move into the A-4 through A-7 territory, things get risky. These are materials where more than 35% passes the No. 200 sieve.

- A-4 and A-5: These are silty soils. They are notorious for frost heave. They suck up water like a straw through capillary action.

- A-6 and A-7: These are the clays. A-6 is your typical plastic clay that shrinks and swells. A-7 is even worse.

Wait, there’s a catch. A-7 is split into A-7-5 and A-7-6. This is where people get tripped up. The distinction is based on the Plasticity Index relative to the Liquid Limit.

- If $PI \le LL - 30$, it’s A-7-5. This soil can be highly elastic and often contains organic matter.

- If $PI > LL - 30$, it’s A-7-6. This is a high-volume-change clay. It’s the stuff that cracks your driveway in the summer and heaves your front porch in the winter.

Common Misconceptions About the AASHTO Chart

One of the biggest mistakes people make is assuming that a "good" soil for a garden is a "good" soil for a road. It's the opposite. Farmers love loamy, organic soil because it holds water and nutrients. Road builders hate it for the exact same reason.

Another big one: thinking AASHTO and USCS are interchangeable. They aren't. USCS uses 50% passing the No. 200 sieve as the cutoff for fines, while AASHTO uses 35%. That 15% difference might seem small, but it changes how you design your pavement thickness. If you try to use USCS classifications for a DOT project, the reviewer will send your report back before they even finish their coffee.

Field Identification: Can You Do It Without a Lab?

Kinda. Sorta.

✨ Don't miss: The Theory of Everything Awards: Why Physics Just Can’t Decide on a Winner

You can’t get a formal classification without a sieve analysis and Atterberg limits, but a seasoned pro can smell an A-7 from a mile away.

- The Ribbon Test: Squeeze a moist lump of soil between your thumb and forefinger. If it forms a long, shiny ribbon before breaking? You’re likely in the A-6 or A-7 range.

- The Jar Test: Drop some soil in water and shake it. If it settles in seconds? It's A-1 or A-3. If the water stays cloudy for hours? That’s the silt and clay of the lower groups.

- The Grittiness Test: Rub some between your teeth. (Yes, people actually do this). If it’s crunchy, it’s sand/gravel. If it’s smooth like flour, it’s silt. If it sticks to your teeth like peanut butter, it’s clay.

Don't actually eat the dirt. Just use your fingers.

Engineering Implications of Your Results

Once you have your AASHTO soil classification chart results, what actually happens next?

The classification dictates the Resilient Modulus ($M_R$), which is a measure of the soil's stiffness under moving loads. A-1 soils have a high $M_R$, meaning you can get away with a thinner asphalt layer. A-7 soils have a low $M_R$, requiring a thick structural section or "undercutting"—where you dig out the bad soil and replace it with something better.

We also have to talk about drainage. A-4 soils are the "pumping" soils. When a heavy truck rolls over a concrete slab on A-4 soil, the pressure forces water and silt up through the joints. This creates a void under the road, leading to those rhythmic "thump-thump" cracks you feel on old highways. If your chart says A-4, you better design a killer drainage system.

Actionable Insights for Project Managers

If you’re overseeing a project and the lab results come back, don't just glance at the A-number. Look at the data behind it.

Check the Liquid Limit (LL). If it’s over 40, you have a soil that is sensitive to moisture.

Watch the Plasticity Index (PI). A PI over 20 usually means you need to consider chemical stabilization—either lime for clays or cement for silty sands.

Verify the sieve results. If the percentage of fines is creeping toward that 35% mark, your soil is on the edge of becoming a drainage nightmare.

Next Steps for Accurate Classification

To ensure your road doesn't crumble in three years, follow these specific steps:

- Representative Sampling: Don't just take soil from the top. Get samples from the actual subgrade elevation.

- Check for Organics: AASHTO doesn't explicitly categorize "peat" in the main chart, but if you see dark, smelly material, the A-groups don't matter—you have to remove it.

- Run the Atterberg Limits: Never skip the $LL$ and $PL$ tests. The difference between an A-4 and an A-6 is purely about the plasticity, and you can't see that with the naked eye.

- Apply the Group Index: Always calculate the GI. It’s the nuance that separates a "manageable" clay from a "project-killing" clay.

Understanding the AASHTO system isn't about memorizing a table. It's about knowing how the ground under your feet is going to react when a 40-ton tractor-trailer zooms over it at 70 miles per hour. Focus on the fines, watch the plasticity, and never underestimate the power of a high Group Index to ruin your day.