Bond markets are usually boring. Most people check their 401(k), see a mix of stocks and "fixed income," and then promptly ignore the latter because, honestly, watching debt mature is about as exciting as watching paint dry in a humidity chamber. But if you’ve been watching the 7 year treasury yield lately, you know things have gotten weird. It’s the "middle child" of the yield curve. It doesn't get the prestige of the 10-year benchmark, and it lacks the raw, caffeinated energy of the 2-year note that reacts to every single word coming out of Jerome Powell’s mouth.

Yet, this specific maturity tells a story about where the US economy is actually headed.

When you look at a Treasury note, you're looking at a loan. You are the lender; the US government is the borrower. The yield is the interest rate they pay you for the privilege of using your cash. Simple. Except that the 7 year treasury yield often acts as a pivot point for the entire mortgage market and corporate lending space. If this number moves, your world gets more expensive. It's that direct.

The awkward physics of the seven-year note

There is a concept in bond trading called "convexity," which is basically a fancy way of saying how much a bond's price moves when interest rates change. The seven-year sits in a precarious spot. It has enough duration—meaning time until you get your principal back—to be sensitive to long-term inflation fears. But it’s also short enough that it gets jerked around by the Federal Reserve’s overnight rate hikes. It’s caught in a tug-of-war.

Lately, we’ve seen the yield curve "invert." That’s the finance world’s version of a fire alarm. Usually, you’d want more interest for locking your money up for ten years than for two. Makes sense, right? Risk equals reward. But when the 7 year treasury yield starts dropping below shorter-term rates, it means the market is betting on a recession. It means investors are so scared of the immediate future that they’re willing to take a lower rate just to park their money safely for the medium term.

Think about the auction process. Every month, the Treasury Department sells these notes. They call it a "7-year auction." If big institutional banks—the Primary Dealers—don't show up with enough appetite, the "tail" of the auction gets long. That’s bad. It means the government had to offer a higher yield than expected just to get people to buy the debt. When the 7-year auction "tails," it ripples through the market instantly. Traders see it as a sign of weak demand for US debt.

Why this number dictates your mortgage (even if you think it's the 10-year)

Most people think the 10-year Treasury is the king of mortgage rates. They’re sort of right, but they’re also missing the nuance. Most homeowners don't actually keep their 30-year mortgage for 30 years. They move. They refinance. They get divorced or they downsize. On average, a "30-year" mortgage actually lasts about seven to ten years.

Because of that, banks often hedge their mortgage portfolios using the 7 year treasury yield.

If you see the 7-year yield spike on a Tuesday morning because of a hot Consumer Price Index (CPI) report, don't be surprised if your mortgage broker calls you on Wednesday with bad news about your "locked" rate. The 7-year is the "sweet spot" for duration for most consumer debt. It’s the engine under the hood of the American housing market.

We saw this play out in the 2023 regional banking crisis. Banks like Silicon Valley Bank had stuffed their balance sheets with mid-duration Treasuries. When the yields rose rapidly, the value of those existing bonds—which were paying much lower interest—plummeted. It wasn't a "bad" investment in terms of credit risk (the US government usually pays its bills), but the interest rate risk was a killer. The 7-year note was right at the center of that valuation collapse.

The psychology of the "belly" of the curve

Traders call the 5-year and 7-year maturities the "belly" of the curve. It’s where the most complex bets happen. If you’re a pension fund manager, you’re looking at the 30-year. If you’re a day trader, you’re looking at the 2-year. But if you’re a macro strategist trying to figure out if the Fed is going to achieve a "soft landing," you’re staring at the 7 year treasury yield.

It represents the market's expectation of the "neutral rate." This is the theoretical interest rate that neither stimulates nor brakes the economy. It’s the Goldilocks zone.

But Goldilocks hasn't lived here in a while.

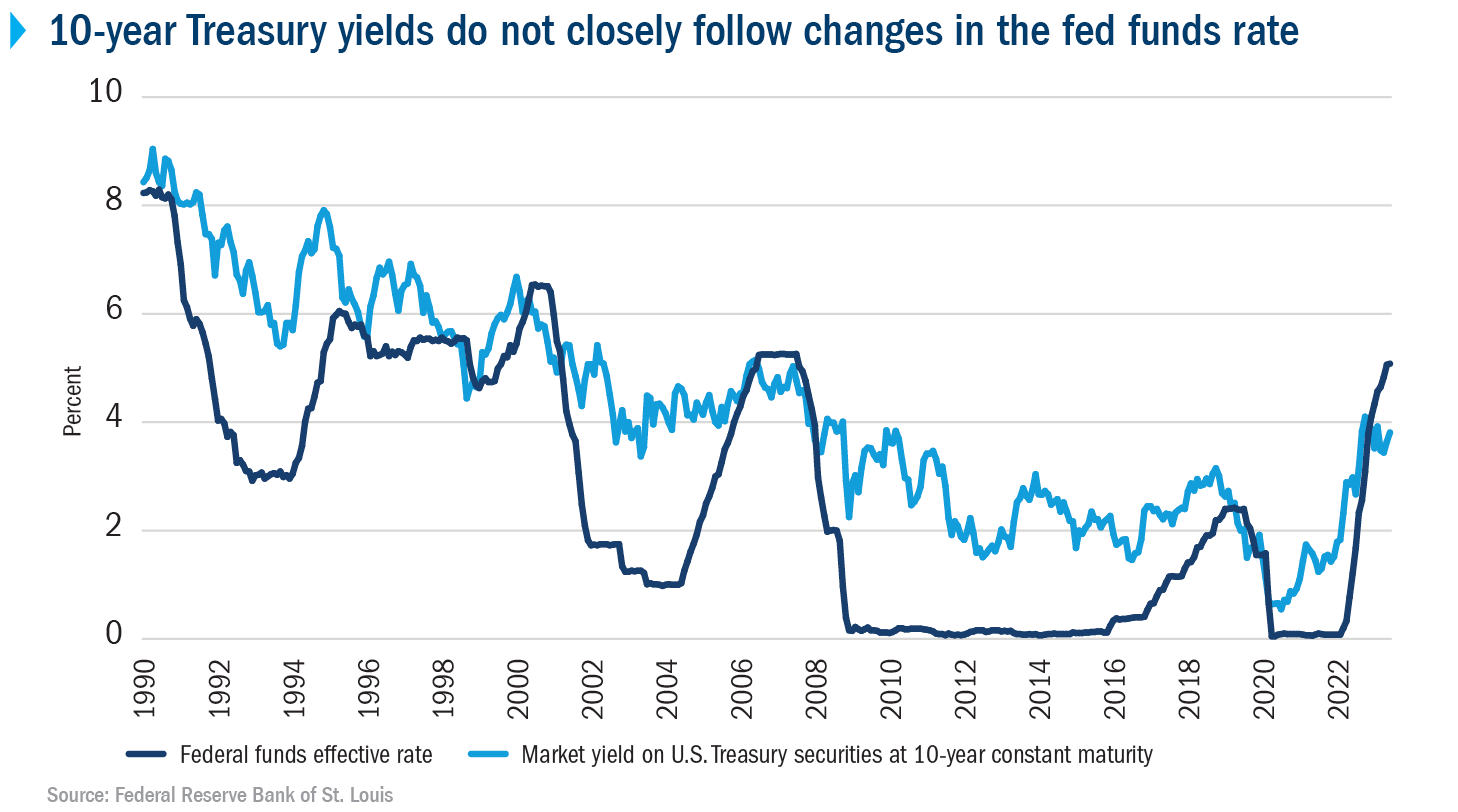

We’ve moved into an era of "higher for longer." For a decade after the 2008 crash, we were used to yields being basically zero. Now, seeing a 7 year treasury yield hovering around 4% or higher feels like a shock to the system. But historically? That’s actually normal. We just forgot what normal felt like because we were addicted to cheap money.

Real talk: Inflation vs. Yield

You have to account for "real yield." This is the 7 year treasury yield minus the expected inflation rate. If the 7-year is paying you 4.5% but inflation is running at 5%, you are effectively paying the government to hold your money. You're losing 0.5% of your purchasing power every year.

That’s why the Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS) market is so closely tied to the 7-year. Investors use these to hedge. When the nominal 7-year yield rises, it’s usually for one of two reasons:

- People expect the economy to grow like crazy.

- People expect inflation to eat their lunch.

Right now, it’s a bit of both, mixed with a healthy dose of anxiety about the US national debt. With the deficit where it is, the Treasury has to issue more and more supply. More supply means prices go down and yields go up. It’s a basic supply-and-demand curve, but with trillions of dollars on the line.

What you should actually do with this information

So, how does a regular person use the 7 year treasury yield without becoming a miserable basement-dwelling bond vigilante?

First, use it as a lead indicator for your own debt. If you are planning on taking out a business loan or a home equity line of credit (HELOC) in the next six months, watch the 7-year. If it starts trending up consistently, your window of opportunity is closing. Stop waiting for a "better" rate that isn't coming.

Second, consider the "ladder" strategy. Instead of dumping all your cash into a savings account that might lower its rate as soon as the Fed cuts, some people buy a "ladder" of Treasuries. You buy a 2-year, a 5-year, and a 7-year. This way, you’re capturing the higher yields of the 7 year treasury yield while keeping some cash becoming available sooner.

Third, keep an eye on the "spread." That’s the difference between the 2-year and the 7-year. If that gap starts widening significantly, it means the market is getting more optimistic about the long term. If it’s narrowing or "flat," buckle up. It means the market thinks the Fed is about to break something.

The unexpected role of international buyers

We can't talk about the 7-year without talking about Japan and China. For decades, they were the biggest buyers of our "belly" debt. But things changed. As the Bank of Japan finally started raising its own rates, Japanese investors—who used to find the 7 year treasury yield incredibly attractive compared to their own 0% rates—started bringing their money home.

When the "big buyers" leave the room, the 7-year gets volatile.

👉 See also: Why is the USD so strong right now? The forces driving the dollar's dominance

We saw a flash of this in late 2023 and throughout 2024. Small shifts in international policy caused massive swings in US yields. This volatility isn't just a number on a screen; it affects the "cost of capital" for every company in the S&P 500. When a company like Apple or Amazon wants to build a new data center, they don't use the cash in their pocket; they issue bonds. And those bonds are priced relative to—you guessed it—the 7 year treasury yield.

Final tactical takeaways

Don't ignore the middle of the curve. It's where the truth usually hides.

- Watch the Auction Results: Check the "Bid-to-Cover" ratio on the monthly 7-year auctions. A ratio below 2.3 is usually a sign of trouble.

- Correlate with Tech Stocks: Growth stocks are incredibly sensitive to the 7-year yield. When the yield goes up, the "present value" of future earnings goes down. Tech drops.

- Check the Real Yield: Don't just look at the headline number. Use the St. Louis Fed's (FRED) database to look at the 7-year breakeven inflation rate.

The 7 year treasury yield is the ultimate "vibe check" for the American economy. It’s not as flashy as the stock market, but it’s the foundation the entire house is built on. If the foundation shifts, the whole house shakes. Stay alert to the shifts in the 7-year, and you'll usually see the market's next move before it actually happens.

To stay ahead, you should monitor the daily Treasury yield curve rates directly from the US Department of the Treasury's official website. Look for trends over a 30-day moving average rather than reacting to single-day "noise." If the 7-year stays consistently above the 10-year, prepare for continued market volatility and consider shifting some of your portfolio into shorter-duration, higher-liquidity assets to wait out the storm.