You're staring at a greasy engine stand, wondering if your bank account can handle another project. It's a common sight. For anyone who has spent time in a garage or scrolled through endless forums, the 5.3 l short block is basically the holy grail of "get it done" engineering. It isn’t the flashy, high-displacement 6.2 L that gets all the YouTube glory, and it isn't the classic 5.7 L small block your dad swears by. Honestly, it’s better because it’s everywhere.

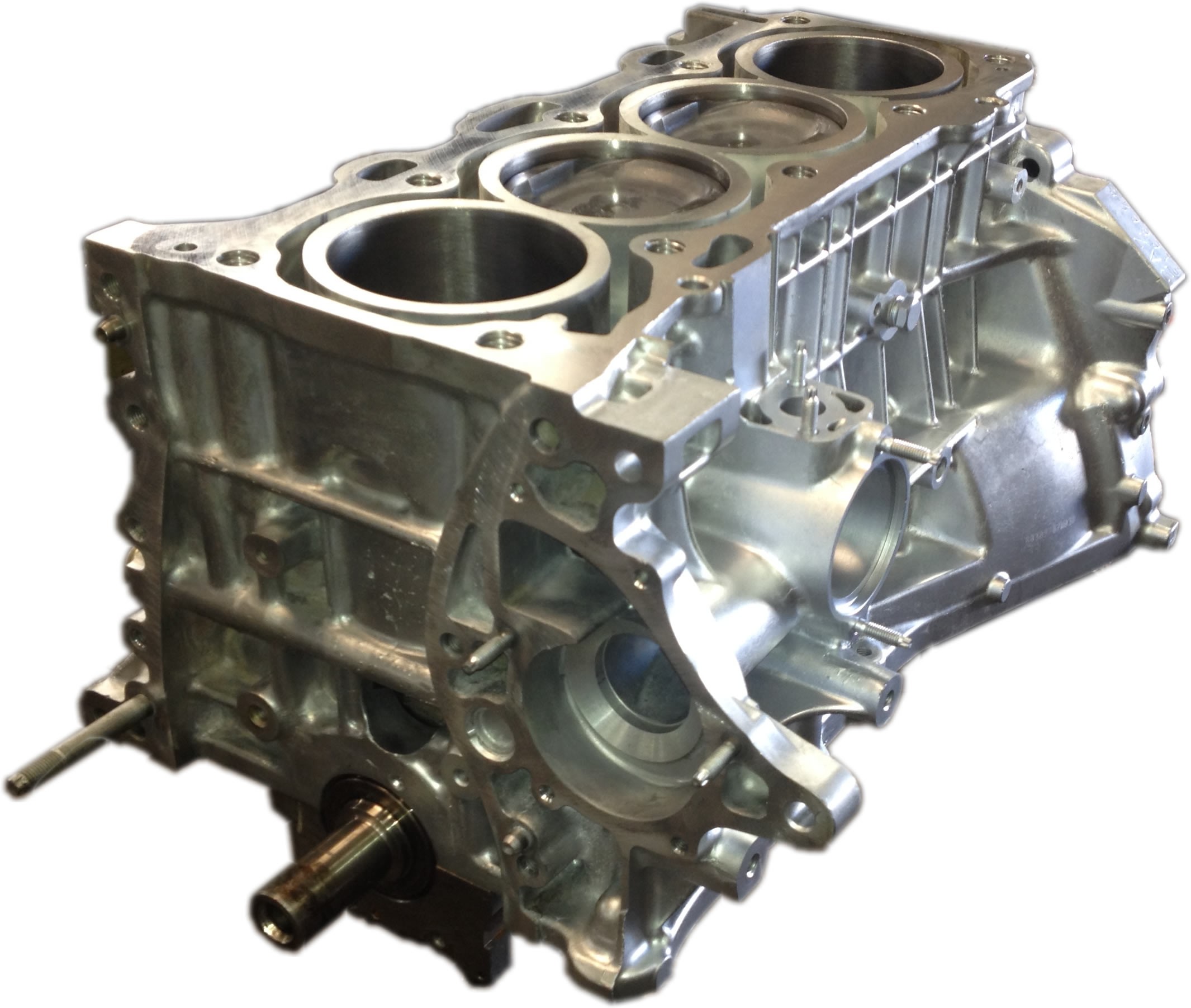

The 5.3-liter engine, part of the legendary General Motors LS family, has become the backbone of the American performance scene. But when we talk about a "short block," we aren't talking about a complete, drop-in-and-fire-it-up engine. We are talking about the foundation. The cast iron or aluminum block, the crankshaft, the connecting rods, and the pistons. No heads. No intake manifold. No oil pan. Just the rotating assembly tucked inside the cylinder walls.

Why does this specific configuration matter so much? Because it's the point of no return for a build.

The Iron vs. Aluminum Identity Crisis

Most people hunting for a 5.3 l short block are looking for the "Iron Giant"—usually the LM7 or the later LY5/LMG variants. Iron blocks are heavy. They’re anchors. But man, can they take a beating. If you are planning on slapping a massive Chinese-made turbocharger onto your build and shoving 20 pounds of boost down its throat, you want the iron. It doesn't flex. It doesn't complain.

Then there’s the aluminum crowd. Engines like the LC9 or the LH6. These are popular in the Pro Touring world where weight distribution actually matters. You save about 80 to 100 pounds off the nose of the car by going aluminum. That is a massive difference in how a vehicle handles a corner. However, you'll pay a premium for it at the junkyard. People know what they have.

There's this weird misconception that the 5.3 is just a "budget" 6.0. That’s technically true, but it misses the point. The 5.3 has thicker cylinder walls in the iron versions. This means you can bore it out. A lot of builders take a standard 5.3 l short block and bore it to 3.898 inches, essentially turning it into a 5.7 L LS1 but with the rigidity of an iron block. It's the "poor man's iron LS1," and it's brilliant.

✨ Don't miss: Stream TV with Auto Play: Why Your Remote Feels Like a Mind Reader (and How to Fix It)

What Actually Lives Inside a Stock 5.3 L Short Block?

If you crack one open, you’re going to find a mixed bag depending on the year. The early stuff (1999-2003) had what we call "weak" rods. They aren't actually weak—they'll still handle 500 horsepower all day—but they have a distinct taper. Around 2004, GM switched to the "Gen 4" style rods. These are beefy. They are full-floating wrist pin units that can reliably handle 700 to 800 wheel horsepower if the tune is right.

The crankshaft is almost always a cast nodular iron piece. It’s tough. You rarely hear about a 5.3 crank snapping unless something went horribly wrong with the oiling system or someone tried to make 1,500 horsepower on a stock part.

- Pistons: Usually eutectic aluminum alloy. They’re fine for naturally aspirated builds but they hate heat. If you're going boosted, the top ring gap is your biggest enemy.

- Bearings: Standard GM stuff. Often look worn even when they aren't.

- Main Caps: Two-bolt? Nope. These are six-bolt mains. Four vertical, two horizontal. It’s why the bottom end stays together at high RPM.

The Problem With "Junkyard Fresh"

We’ve all seen the videos. Someone pulls a 5.3 l short block out of a wrecked 2005 Silverado, sprays it with some degreaser, and runs 10s in the quarter mile. It happens. But it’s a gamble.

When you buy a used short block, you’re trusting the previous owner actually changed their oil. Often, they didn’t. You'll pull the windage tray and find a thick layer of "forbidden chocolate milkshake" or, worse, glitter.

The lifter trays are another failure point. In a short block, the lifters sit in plastic buckets. Over time, these buckets get brittle. If a lifter turns sideways because the tray failed, it eats the camshaft. Since the cam is part of the short block assembly (usually), your "cheap" foundation just became a paperweight.

Why Gen IV is the Sweet Spot

If you have the choice, you want a Gen IV 5.3 l short block. These are roughly 2007 to 2014. Why? The rods, mostly. But also the block casting itself is generally refined. You get better oiling passages and more robust sensors.

The downside? Displacement on Demand (DOD) or Active Fuel Management (AFM).

These systems are garbage for performance. They use special lifters that collapse to deactivate cylinders. When buying a used short block, you almost always have to "delete" this. It involves swapping the lifters, the lifter trays, and the oil manifold cover. It's an extra $300 to $500 you have to factor into the price. If you don't do it, the AFM lifters will eventually fail. It’s not a matter of if; it’s when.

Understanding Displacement Limits

You can’t just keep boring these things out forever. While the iron blocks are thick, the aluminum ones use sleeves. If you go too far on an aluminum 5.3, you’ll hit water.

Most experts, like those over at Texas Speed or Thompson Motorsports, will tell you that a .030 overbore is safe for almost any iron 5.3. Some guys go .060 to reach that 5.7 L bore size. It works, but your cooling system better be top-notch because the thinner walls transfer heat differently.

The Real Cost of a 5.3 L Short Block Build

Let’s be real about the money.

A "core" block from a yard might cost you $300. But by the time you take it to a machine shop to get it hot-tanked, decked, and honed, you're in for another $600. Add in a set of decent rings, bearings, and maybe some ARP rod bolts, and your "cheap" 5.3 l short block is suddenly a $1,500 investment.

Is it worth it?

Compare that to a crate engine. A brand-new SP350/357 from Chevy Performance will run you five grand. A built 5.3 will outrun it and handle twice the abuse for half the price. It’s the math of the street.

Common Misconceptions That Kill Engines

One of the biggest lies in the car world is that "any LS is a good LS."

While the architecture is great, the 5.3 has specific quirks. For instance, the oil pump. The O-ring on the pickup tube is the number one killer of these short blocks. If that little rubber ring gets pinched during assembly or gets brittle with age, the pump sucks air. Air doesn't lubricate bearings. Your oil pressure drops, and three seconds later, your 5.3 is junk.

Another thing: Steam ports.

The LS engine is designed to sit at an angle. Air pockets get trapped in the top of the block and heads. If you block off the steam ports on your 5.3 l short block build because you want a "clean look," you’re inviting localized hotspots that will crack a piston land. Don't do it.

Practical Steps for Your Build

If you are ready to pull the trigger on a 5.3 project, don't just buy the first one you see on Marketplace.

First, decide on your power goal. If you want under 600 horsepower, a stock-bottom-end (SBE) Gen III iron block is fine. If you want to push 800 or more, find a Gen IV iron block and plan on upgrading to forged pistons.

Second, check the head bolt holes. The Gen III blocks use two different lengths of head bolts. Gen IV uses all one length. If you try to shove a Gen III bolt into a Gen IV block, you will crack the casting. It's an amateur mistake that ruins an otherwise perfect short block.

Third, look at the reluctor wheel on the crankshaft. It’s either 24x (usually black sensor) or 58x (usually grey sensor). Your ECU has to match this. You can't easily swap them without pulling the whole crank and taking it to a machine shop.

Finalizing the Foundation

The 5.3 l short block remains the king of the aftermarket for a reason. It is the perfect balance of cost, weight, and durability. Whether you’re building a drift car, a tow rig, or just a fun weekend cruiser, this platform offers more "bang for the buck" than almost anything else in automotive history.

Don't overthink the "big block" dreams if you don't have the "big block" budget. A well-assembled 5.3 will do everything you need it to do. Focus on the basics: clean oil, a good tune, and a solid rotating assembly.

Next Steps for Your Project:

- Verify the Generation: Check the valley cover and sensor locations to ensure you're buying the Gen IV internals if you plan on high boost.

- Inspect the Cylinder Walls: Look for the factory cross-hatch. If the walls are "mirrored" or have vertical scoring you can feel with a fingernail, factor in the cost of a bore and hone.

- Address the Oil System: Always replace the oil pump O-ring with a high-quality Viton version and use a new high-volume pump if you're running an aftermarket camshaft.

- Match Your Parts: Ensure your cylinder head choice matches the bore size; putting large-valve 6.0 L heads on a 5.3 L bore can lead to valve-shrouding and lost power.