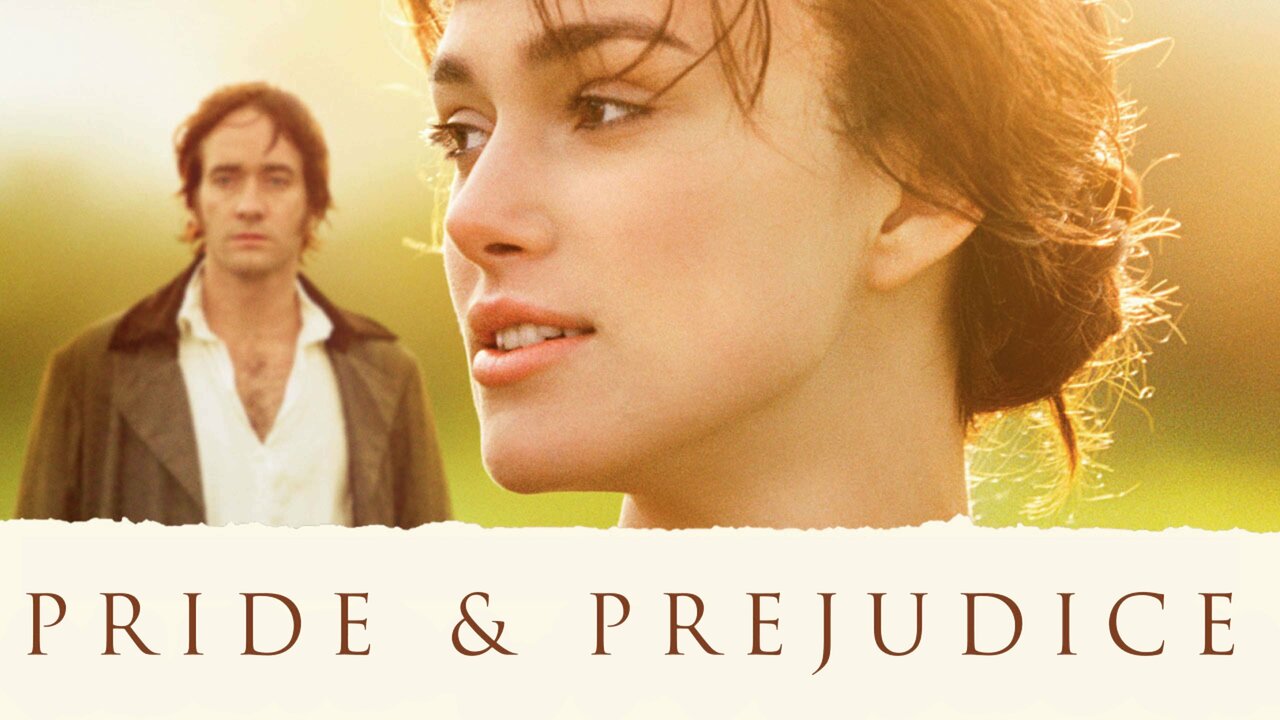

It was the hand flex. You know the one. Matthew Macfadyen walks away from Keira Knightley after helping her into a carriage, and his fingers twitch in this silent, agonizing burst of repressed longing. Honestly, that single second of film probably did more for the 2005 Pride & Prejudice legacy than any marketing campaign ever could. It wasn't in the book. It wasn't in the 1995 BBC miniseries that everyone compares it to. It was just pure, unadulterated Joe Wright filmmaking.

People are still fighting about this movie twenty years later. Some folks swear by Jennifer Ehle and Colin Firth, and I get it. I really do. That version is literal. It’s a transcription of Jane Austen’s 1813 novel. But the 2005 Pride & Prejudice isn’t interested in being a transcription. It wants to be a mood. It wants you to feel the mud on the hem of Elizabeth Bennet's dress and the actual, suffocating pressure of being poor in the English countryside when your only career path is "marrying well."

The Gritty Reality of Longbourn

Most period dramas look like they were filmed inside a porcelain shop. Everything is clean. Everyone’s hair is perfectly coiffed. But when Joe Wright took on the 2005 Pride & Prejudice, he decided he wanted things to look a bit... gross. Not "Lord of the Rings" gross, but real. Longbourn, the Bennet family home, feels like a working farm because it is one. There are geese running through the house. There’s laundry hanging everywhere. You can practically smell the dampness in the air.

This wasn't just a stylistic choice. It was a narrative one. In the 1995 version, the Bennets look pretty wealthy. They’ve got nice clothes and a big house. But in the 2005 Pride & Prejudice, you see the stakes. If Mr. Bennet dies, these girls are in serious trouble. They aren't living in a palace; they're living in a house where the wallpaper is peeling and the floors are scuffed.

Knightley and Macfadyen: A Different Kind of Chemistry

Keira Knightley was only 19 or 20 when she filmed this. Think about that. She was actually the age Elizabeth Bennet is supposed to be. Some critics at the time, like the late Roger Ebert, noted that she brought a certain "modernity" to the role, which some Janeites found jarring. She’s tomboyish. She’s messy. She laughs too loud. But isn't that the point? Elizabeth is supposed to be the one who doesn't fit the "accomplished woman" mold.

✨ Don't miss: Cuba Gooding Jr OJ: Why the Performance Everyone Hated Was Actually Genius

Then there’s Matthew Macfadyen’s Mr. Darcy.

If Colin Firth was the "stiff upper lip" Darcy, Macfadyen is the "socially anxious" Darcy. He’s not being a jerk because he thinks he’s better than everyone (well, maybe a little), but he’s mostly just miserable in crowds. Watch the scene at the Meryton ball again. He looks like he wants to melt into the floorboards. It makes his eventual declaration of love feel less like a condescending offer and more like a desperate outburst. It’s vulnerable. It’s awkward. It’s human.

The Cinematography That Changed Everything

We have to talk about Roman Osin. He was the cinematographer for the 2005 Pride & Prejudice, and he used these long, sweeping tracking shots that were pretty revolutionary for a costume drama. The scene at the Netherfield ball is the best example. The camera follows the characters through rooms, around dancers, and into private conversations without a single cut.

It makes the viewer feel like a guest at the party. You aren't just watching a play; you're moving through the space. This fluidity is part of why the movie feels so much faster than the book. It’s lean. It’s mean. It cuts out the fluff. Of course, that’s exactly what makes the purists scream. They miss the Wickham subplot details and the Aunt Gardiner scenes. And yeah, those are great in the book, but in a two-hour movie? You gotta kill your darlings.

🔗 Read more: Greatest Rock and Roll Singers of All Time: Why the Legends Still Own the Mic

That Second Proposal

The "Mist Scene." You know it. It’s dawn. The grass is dewy. Elizabeth is in her nightgown and a coat. Darcy appears out of the fog with his coat flapping in the wind.

Logically? It’s ridiculous. No Regency gentleman would ever walk across a field in his pajamas to propose to a woman he’s already been rejected by. It’s a total departure from the etiquette of the time. But cinematically? It’s incredible. The 2005 Pride & Prejudice leans into the Romanticism (capital R) of the era. It’s influenced by Wordsworth and Coleridge more than the dry wit of the 18th-century Enlightenment. It’s about the feeling of being in love, not just the social contract of marriage.

Why it Still Trends on Social Media

If you go on TikTok or Instagram today, the 2005 Pride & Prejudice is everywhere. Why? Because it’s "aesthetic." The "cottagecore" movement owes half its existence to this movie. The soft lighting, the focus on nature, the piano-heavy score by Dario Marianelli—it all taps into a specific kind of longing.

Marianelli’s score is actually a character itself. He used a "period-accurate" piano, which has a thinner, more percussive sound than a modern grand. It sounds like someone is playing it in the room with you. When Elizabeth plays at Rosings, she isn't a virtuoso. She’s okay. The music reflects that. It’s grounded.

💡 You might also like: Ted Nugent State of Shock: Why This 1979 Album Divides Fans Today

Addressing the Controversies

Let's be real: people have some valid gripes. The costumes are a bit all over the place. Some of the dresses look more 1790s than 1810s. The "US Ending" where Darcy and Elizabeth are kissing on the balcony at Pemberley? A lot of UK fans hated it so much it was originally cut from the British release. They thought it was too sentimental.

Also, the portrayal of Mr. Bennet is a bit softer than in the book. In Austen’s writing, Mr. Bennet is kind of a jerk. He’s checked out and lets his family fall apart. Donald Sutherland plays him with a lot more warmth. It changes the family dynamic. It makes the Bennets feel like a unit that actually loves each other, rather than just a group of people trapped in a house together.

How to Watch the 2005 Pride & Prejudice Like an Expert

If you want to actually appreciate what Wright was doing, you have to look past the romance. Look at the mirrors. The movie is obsessed with reflections. Elizabeth is constantly looking at herself or being framed by windows. It’s a movie about perspective—about how we see people and how we’re seen.

- Watch the background: In the scenes at Longbourn, look at what the other sisters are doing. They aren't just standing there. They're fighting, they're doing chores, they're living. It’s a busy, noisy house.

- Listen to the silence: The 2005 Pride & Prejudice uses silence better than almost any other adaptation. The long pauses between Darcy and Elizabeth during their first proposal at Hunsford are excruciating in the best way.

- Check the weather: Notice how the weather shifts with the mood. The rain at Hunsford, the golden hour at Pemberley, the grey fog at the end. It’s pathetic fallacy at its finest.

Actionable Takeaways for Your Next Rewatch

To get the most out of your next viewing of the 2005 Pride & Prejudice, try these specific things:

- Compare the "First Proposal" scenes: Watch the 1995 version and the 2005 version back-to-back. Notice how the 2005 version uses the architecture—the rain-soaked temple—to create physical tension that the BBC version lacks.

- Track the "Hand Motif": From the carriage scene to the moment Darcy helps Elizabeth into the carriage at Pemberley, watch how their physical contact (or lack thereof) tells the story.

- Read the script's deleted scenes: Deborah Moggach wrote the screenplay, and there are several scenes that didn't make the cut which explain more of the Wickham/Lydia fallout. Knowing these helps fill the narrative gaps.

- Listen to the soundtrack separately: Dario Marianelli’s "Dawn" and "Mrs. Darcy" are masterclasses in how to use solo piano to evoke a specific historical period without sounding like a museum piece.

The 2005 Pride & Prejudice isn't just a movie; it's a mood that hasn't faded. Whether you're a die-hard Austen fan or just someone who likes a good "enemies-to-lovers" trope, it remains the gold standard for how to make the 19th century feel like it's happening right now. It’s messy, it’s muddy, and it’s perfectly imperfect.