Numbers lie. Or, at the very least, they're really good at hiding the truth when you're staring at two different groups and trying to figure out if the gap between them actually matters. You see it everywhere. One marketing campaign has a 4% conversion rate, and the other has 5%. Is that a win? Or is it just noise? That’s exactly why people go hunting for a 2 prop z test calculator. It’s the tool that stops the guessing games.

Honestly, statistics can feel like a gatekeeper. It’s full of Greek letters and intimidating terms like "null hypothesis" or "standard error." But at its core, this specific test is just a way to ask: "Is this difference real, or did I just get lucky with my sample?"

The "So What" factor of the 2 prop z test calculator

Let’s say you’re running a clinical trial. Group A takes a new vitamin, and 20% report feeling more energetic. Group B takes a sugar pill, and 18% say the same. On paper, the vitamin looks better. In reality, that 2% difference might be totally meaningless. If you only tested ten people, that 2% is a fluke. If you tested ten thousand, it’s a breakthrough.

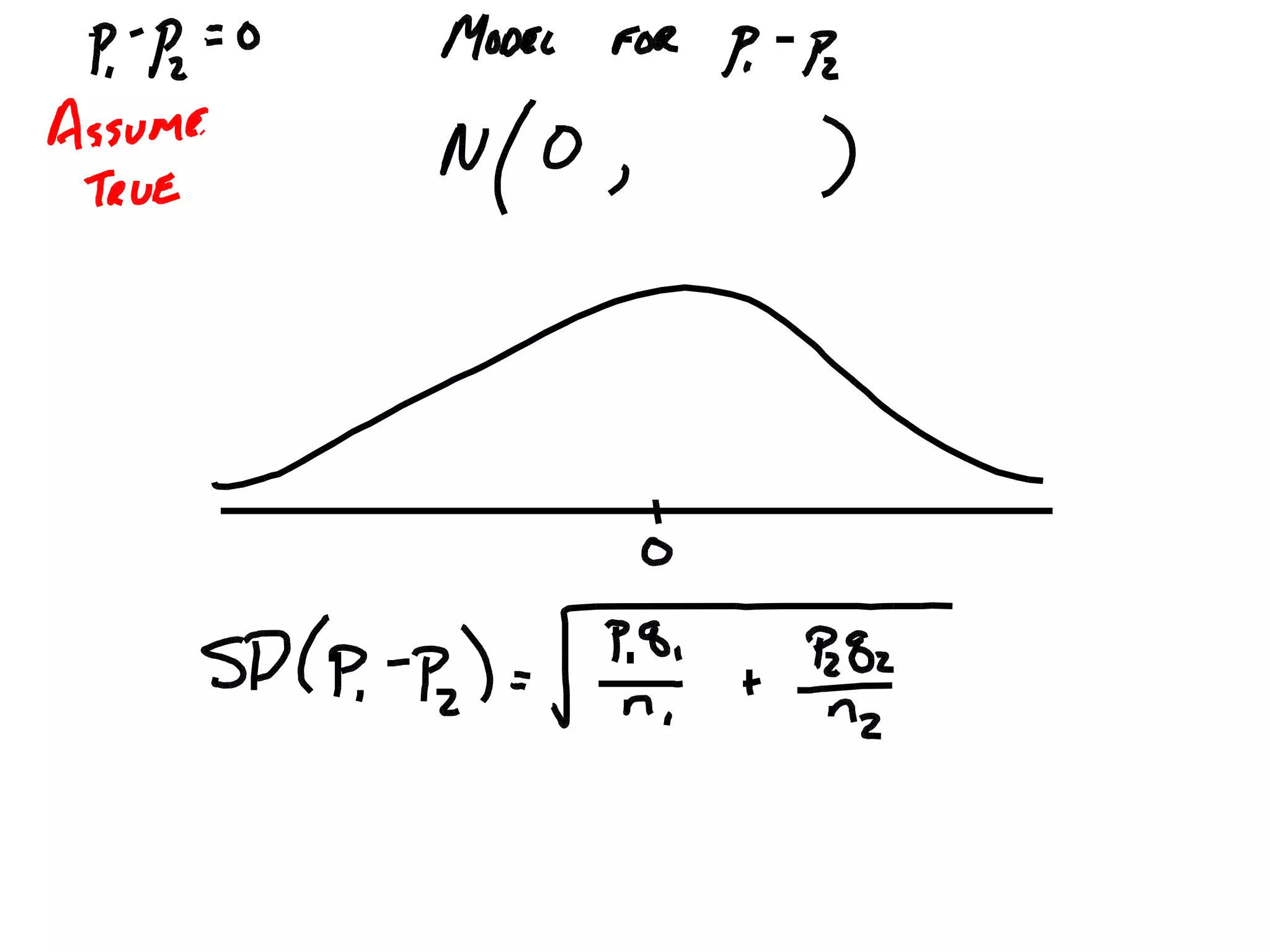

The 2 prop z test calculator does the heavy lifting of figuring out that scale. It uses a normal distribution—that classic bell curve—to see where your data sits. If your "z-score" is high enough, you’ve found something significant. If it’s low, you’re basically looking at a coin flip.

Most people stumble because they don't realize this test has rules. You can't just throw any two numbers in there. You need "independent" groups. If you're testing the same people before and after a treatment, stop. You’re using the wrong tool. That’s a paired test. The 2-proportion test is for when Group A has nothing to do with Group B. Think Mac users vs. PC users, or voters in Texas vs. voters in Florida.

When the math actually clicks

To get a result, the calculator needs four things: the number of successes in group one, the total sample size of group one, and the same two figures for group two. Success doesn't have to be "good," by the way. In stats, a "success" is just the event you're counting. It could be deaths, clicks, or broken widgets.

The formula it runs in the background looks like a nightmare. It involves calculating a pooled proportion, which is basically a weighted average of both groups.

💡 You might also like: Heavy Aircraft Integrated Avionics: Why the Cockpit is Becoming a Giant Smartphone

$$z = \frac{(\hat{p}_1 - \hat{p}_2) - 0}{\sqrt{\hat{p}(1 - \hat{p})(\frac{1}{n_1} + \frac{1}{n_2})}}$$

See? It's gross. That’s why we use calculators. You shouldn't be doing that by hand in a coffee shop unless you're trying to impress a very specific type of nerd.

Real world wins and where it gets tricky

I remember talking to a product manager who was convinced a blue "Buy Now" button was outperforming a red one. The blue was at 12% and the red was at 11.5%. He was ready to rewrite the entire brand guideline based on that half-percent. We ran it through a 2 prop z test calculator. The p-value came back at 0.45.

For the non-math folks, a p-value of 0.45 means there's a 45% chance that the difference was just random luck. Usually, in science or business, we want that number to be under 0.05 (or 5%) to call it "statistically significant." He was about to waste thousands of dollars on a "hunch" that was essentially a toss-up.

The Success-Failure Condition

Here is the part where most online tutorials fail you. They don't mention the "Success-Failure Condition." For a z-test to be valid, you need at least 10 successes and 10 failures in each group. If you're looking at a rare disease where only 2 people recovered, the z-test is going to give you a garbage answer. In those cases, you need "Fisher’s Exact Test." It’s more robust for tiny samples.

Don't ignore the sample size. If your sample is too small, your "power"—the ability to actually detect a difference—is basically zero. It's like trying to look at bacteria with a magnifying glass instead of a microscope. You're just not going to see what's actually there.

📖 Related: Astronauts Stuck in Space: What Really Happens When the Return Flight Gets Cancelled

Why Google Sheets isn't always enough

Sure, you can build your own 2 prop z test calculator in Excel or Sheets. It's just a bunch of nested formulas. But humans are bad at nesting formulas. One misplaced parenthesis and your p-value is suddenly 1.2 (which is impossible, since probabilities only go up to 1).

Dedicated calculators, like those found on sites like Social Science Statistics or even the high-end graphing calculators from TI, usually handle the "tails" better. Are you doing a one-tailed test or a two-tailed test?

- One-tailed: You only care if Group A is better than Group B.

- Two-tailed: You just want to know if they are different in any way.

Most people should use a two-tailed test. It’s more conservative. It’s harder to pass. It keeps you honest.

Common traps to avoid

One big mistake is "data dredging." This is when you run twenty different tests on the same data set until one of them finally hits that "p < 0.05" mark. If you look long enough, you'll find a pattern that isn't there. It's like seeing a cloud that looks like a dog and concluding that the sky is made of poodles.

Another trap? Ignoring the "n." A tiny difference in a massive sample size can be statistically significant but practically useless. If a new drug lowers blood pressure by 0.1 points more than the old one, and you test a million people, the 2 prop z test calculator will scream "SUCCESS!" But a doctor will tell you that 0.1 points doesn't change a patient's life.

Always ask: is this statistically significant and practically significant?

👉 See also: EU DMA Enforcement News Today: Why the "Consent or Pay" Wars Are Just Getting Started

How to actually use the results

Once you've plugged your numbers in and the calculator spits out that z-score and p-value, what do you do?

If $p < 0.05$, you "reject the null hypothesis." In plain English: something is happening here. You can say with some confidence that the difference between your groups isn't just a fluke.

If $p > 0.05$, you "fail to reject." That doesn't mean the groups are identical. It just means you don't have enough evidence to prove they are different. Maybe you need a bigger sample. Maybe the effect is just really subtle. Or maybe, quite simply, there is no difference.

The Ethics of the Z-Test

We don't talk about this enough, but how you collect your data matters more than the calculator itself. If you're comparing two groups but you "cherry-picked" the people in Group A because you wanted them to succeed, the math is tainted. A 2 prop z test calculator is a "garbage in, garbage out" machine. It assumes your samples were random and representative. If they weren't, the result is a lie.

I've seen marketing teams only survey "happy" customers for a new feature and then compare them against a general pool of old users. Of course the new feature looks better. But the math is fraudulent because the groups weren't comparable from the jump.

Actionable Steps for your Data

Don't just take the calculator's word as gospel. Follow these steps to make sure your analysis actually holds water:

- Check your counts. Ensure you have at least 10 "successes" and 10 "failures" in both groups before even opening a calculator. If not, look for an "Exact Test" instead.

- Choose your tails. Decide if you are looking for any difference (two-tailed) or a specific direction (one-tailed) before you see the data. Changing this after the fact is cheating.

- Calculate the Confidence Interval. Most good 2 prop z test calculator tools will also give you a 95% confidence interval. This tells you the range where the "true" difference likely lives. If that range includes zero, be skeptical.

- Consider the "Why." Statistics tell you that a difference exists, but they never tell you why. If your B version of a website is outperforming A, the test won't tell you if it's because of the color, the font, or the fact that it loaded 0.2 seconds faster.

- Verify Independence. Make sure there's no overlap. If someone could be in both Group A and Group B, your z-test is technically invalid.

The best way to get comfortable is to run a few "A/A tests." Take the same group of data, split it randomly in half, and run the test. You should see a non-significant result most of the time. If you start seeing "significance" in identical data, you know you're either dealing with a rare 5% fluke or your methodology is broken.

Data doesn't have to be scary. It's just a tool for telling better stories. Use the calculator to filter out the noise, but keep your eyes on the actual human behavior behind the numbers. That’s where the real insights are hiding.