If you were looking at the weather maps back in the summer of 1997, you probably thought something was broken. Usually, by August, the Atlantic is a conveyor belt of tropical waves marching off the African coast. But that year? It was a ghost town. Honestly, the 1997 Atlantic hurricane season was a complete anomaly that caught a lot of people off guard, even though the experts knew exactly why it was happening.

It was the year of the "Monster El Niño."

Usually, a quiet season is a relief. But 1997 was unsettling because of the sheer silence. We’re talking about a season that produced only seven named storms. To put that in perspective, the average at the time was around ten, and nowadays we regularly see seasons blast past twenty. It wasn’t just the low number of storms that made it weird; it was where they went—or rather, where they didn't go.

The El Niño Factor: Why 1997 Stayed So Quiet

You can’t talk about the 1997 Atlantic hurricane season without talking about the Pacific Ocean. It sounds counterintuitive, I know. Why does the water temperature off the coast of Peru matter for a hurricane trying to form near Florida?

Physics.

That year saw one of the most powerful El Niño events in recorded history. When the Pacific warms up like that, it triggers a domino effect in the upper atmosphere. It creates massive amounts of vertical wind shear across the Atlantic basin. Think of wind shear like a giant pair of scissors. For a hurricane to grow, it needs to stand up straight. It needs to stack its thunderstorms vertically. But in 1997, the winds in the upper atmosphere were screaming across the ocean, basically lopping the tops off any storm that tried to organize.

It was a hostile environment.

✨ Don't miss: Will Palestine Ever Be Free: What Most People Get Wrong

Dr. William Gray, the pioneer of seasonal hurricane forecasting at Colorado State University, had seen these patterns before, but 1997 was extreme. Even though the sea surface temperatures in the Atlantic were warm enough to fuel monsters, the atmosphere simply wouldn't allow it. It's kind of like having a Ferrari with no tires. All that power, but nowhere to go.

Breaking Down the Numbers

Let's look at the actual roster from that year. It’s a short list.

We had Ana, Bill, Claudette, Danny, Erika, Fabian, and Grace. That’s it. No "H" storm. No "I" storm. Compare that to 2005 or 2020, where we ran out of names and had to use the Greek alphabet.

Seven named storms. Three of those became hurricanes. Only one—Erika—reached major hurricane status (Category 3 or higher). If you were a hurricane tracker back then, you were probably bored out of your mind for most of September.

Danny and Erika: The Only Real Headliners

Even in a "dead" year, things can get ugly.

Hurricane Danny was the oddball of the 1997 Atlantic hurricane season. It didn't start in the deep tropics; it formed in the northern Gulf of Mexico in mid-July. It was a slow, lumbering Category 1 storm that pulled a bizarre move by crossing over the Mississippi River delta and then just... sat there.

🔗 Read more: JD Vance River Raised Controversy: What Really Happened in Ohio

It stalled over Alabama.

Because it wasn't moving, it just dumped. We are talking about biblical amounts of rain. Dauphin Island, Alabama, recorded over 36 inches of rainfall. Imagine three feet of water falling from the sky in one event. It caused massive flooding, ruined crops, and was a stark reminder that you don't need a Category 5 "superstorm" to cause a billion dollars in damage.

Then there was Erika.

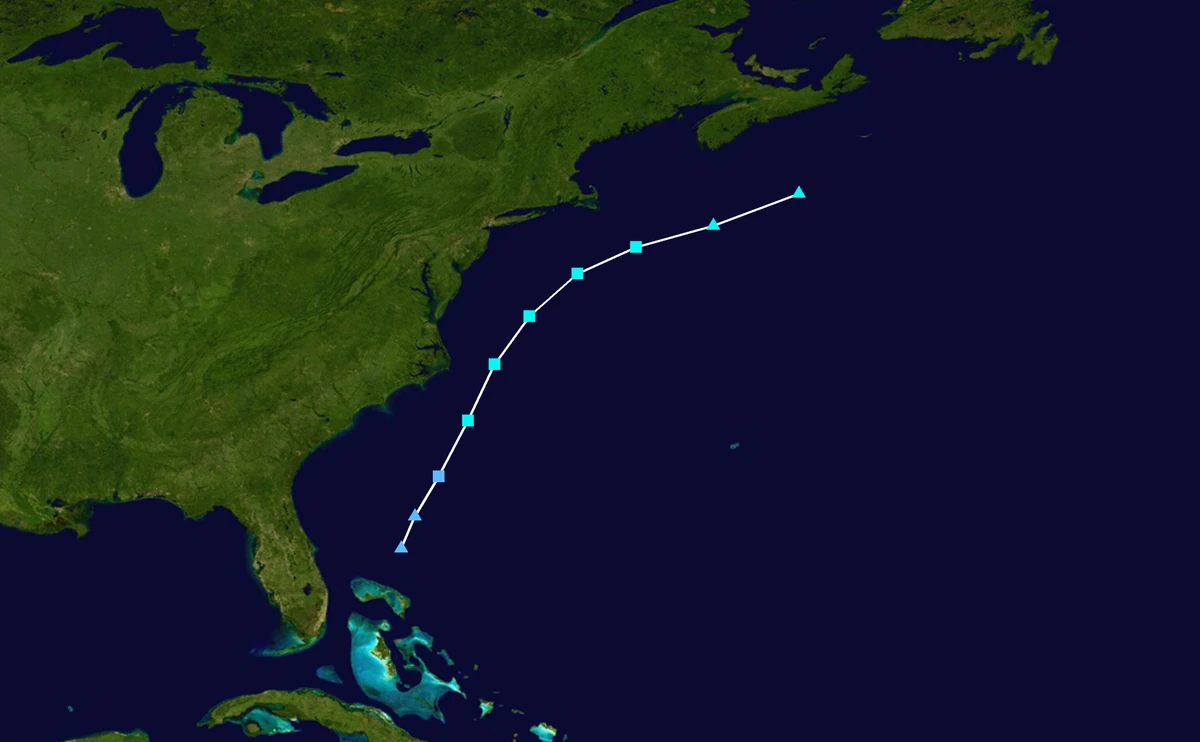

Erika was the powerhouse of the 1997 Atlantic hurricane season. It reached Category 3 strength with winds of 125 mph. For a while, it looked like it might actually threaten the Northern Leeward Islands, but the wind shear—that same El Niño-driven shear—eventually pushed it away and weakened it. It stayed out at sea, mostly bothering shipping lanes and giving meteorologists something to look at on satellite imagery.

The Long-Term Impact on Forecasting

People often ask if 1997 was a "failed" season. From a human safety standpoint? It was a win. Fewer storms usually mean fewer deaths and less property damage. But from a scientific standpoint, it was a masterclass in climatology.

It proved that the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is the single most important variable for seasonal prediction. Before the 90s, we didn't have the same level of satellite data or ocean buoy networks we have now. 1997 was a "live-fire" test of our ability to predict how the Pacific influences the Atlantic.

💡 You might also like: Who's the Next Pope: Why Most Predictions Are Basically Guesswork

- Wind Shear is King: You can have 90-degree water, but if the upper-level winds are 50 knots, nothing is forming.

- Localized Flooding Matters: Danny showed that weak-looking storms can be more dangerous than fast-moving majors because of the rain.

- The "Cape Verde" Silence: Usually, the most dangerous storms come from Africa. In 1997, that "conveyor belt" was effectively shut down.

Interestingly, the very next year—1998—the Atlantic swung back with a vengeance. Once the El Niño faded, the 1998 season delivered 14 named storms, including the devastating Hurricane Mitch. It was like the ocean was making up for lost time.

What This Means for Today’s Seasons

You might think 1997 is just ancient history, but we’re seeing similar patterns emerge in the mid-2020s. Every time an El Niño is announced, people look back at the 1997 Atlantic hurricane season as the gold standard for what a suppressed year looks like.

But there’s a catch now.

The oceans are significantly warmer than they were in 1997. In the modern era, we've seen "hybrid" years where we have an El Niño and a busy hurricane season because the water is so incredibly hot that it sometimes overcomes the wind shear. 1997 was a simpler time in that regard; the shear won the battle easily.

If you’re living on the coast, the lesson of 1997 isn't "El Niño means I'm safe." The lesson is that it only takes one. One Hurricane Danny sitting over your house for two days is just as life-altering as a major hurricane.

Actionable Steps for Future Seasons

If you're tracking the tropics or living in a hurricane-prone area, don't let a "quiet" forecast lure you into a false sense of security.

- Look at the "Shear" Maps, Not Just the "Heat" Maps: High water temperatures are only half the story. Check the 200mb wind patterns to see if storms can actually survive.

- Focus on Rainfall Potential: If a storm is predicted to be a "slow mover," ignore the Category rating. Water kills more people than wind.

- Prepare for the "Post-El Niño" Snapback: History shows that quiet years often precede incredibly active ones. If this year is quiet, use the time to harden your home for the next one.

- Monitor the MDR: The Main Development Region between Africa and the Caribbean is the heart of the season. If it's quiet there, the "Cape Verde" season is likely a bust.

The 1997 Atlantic hurricane season remains a fascinating case study. It was a year when the atmosphere essentially told the ocean to "pipe down." It gave us a break, but it also gave us a wealth of data that helps us predict the monsters we face today.