October 11, 1975. Studio 8H. It was a mess. George Carlin was high, the writers were terrified, and NBC executives were basically hovering over the "off" switch like it was a detonator. When we talk about 1975 Saturday Night Live, people usually default to the "Best Of" clips—the Bee Girl, the Land Shark, or Chevy Chase falling over a podium. But that’s the sanitized version. The reality was a group of twenty-somethings who genuinely didn't think they’d have a job by Monday morning.

It wasn't even called Saturday Night Live back then because Howard Cosell had a show with that name on ABC. It was NBC’s Saturday Night. And it was weird.

The Night Everything Changed for TV

Lorne Michaels was only 30. He’d convinced NBC to give him the 11:30 p.m. slot because they were tired of running reruns of The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson. Carson wanted those reruns moved to weeknights so he could take more time off. That’s the only reason SNL exists. It was a corporate scheduling solution that accidentally birthed a counter-culture revolution.

The first episode was a chaotic variety hour. It had two musical guests (Janis Ian and Billy Preston), a stand-up monologue by Carlin, and even a segment with Jim Henson’s Muppets. Yeah, the Muppets. But these weren't the "Elmo" Muppets. They were "The Land of Gorch," a collection of swamp-dwelling creatures that even the writers hated. Head writer Michael O'Donoghue famously refused to write for them, saying he didn't write for "felt."

You could feel the friction. The show was trying to be five things at once. It was a sketch show, a concert, a political statement, and a middle finger to the establishment.

Why the Cast Was "Not Ready For Prime Time"

They weren't stars. They were the "Not Ready For Prime Time Players."

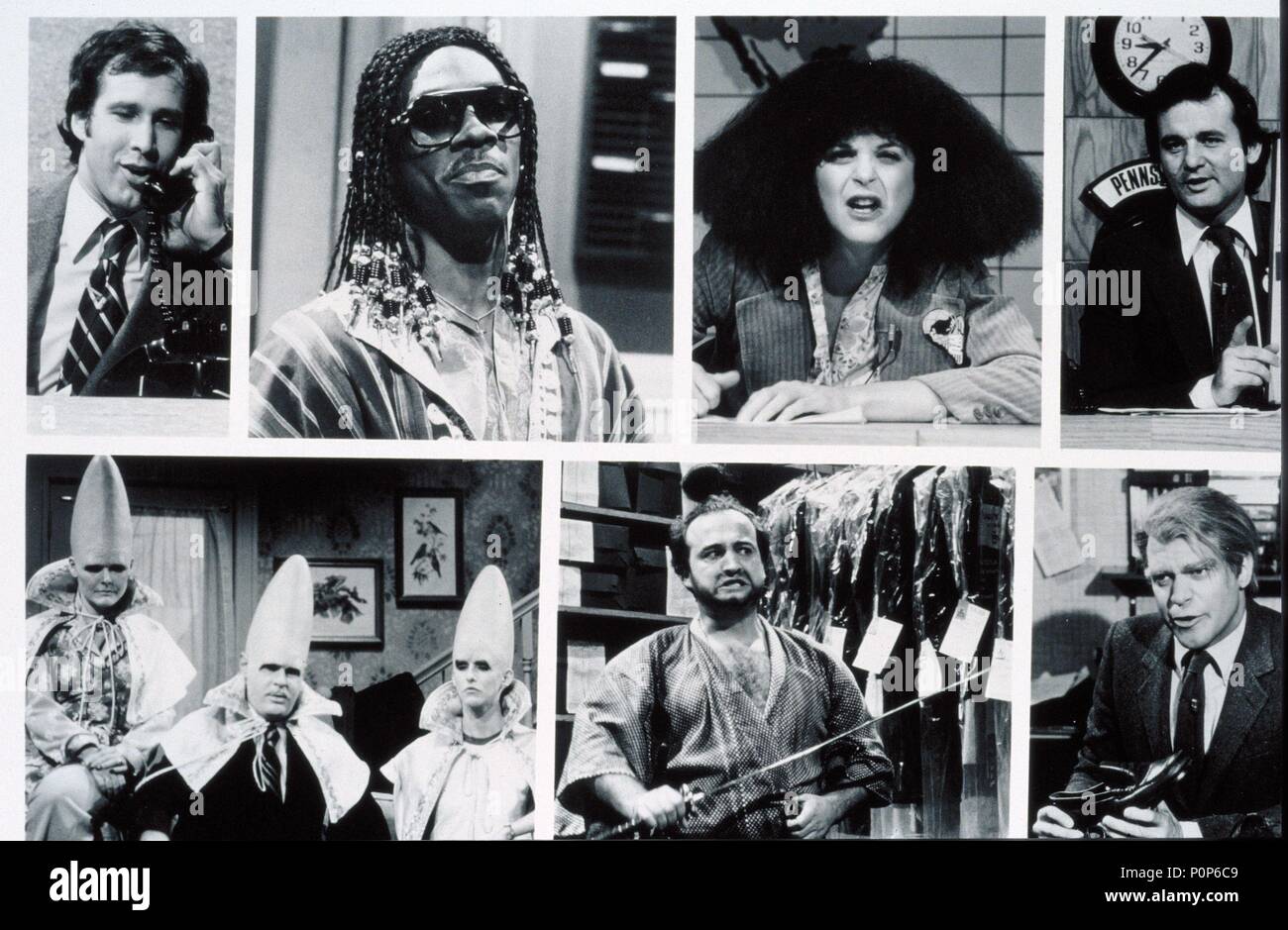

John Belushi was a force of nature from Second City. Dan Aykroyd was a Canadian obsessed with blues and police radios. Gilda Radner was the heart of the room. Jane Curtin was the "straight" one who could anchor any absurdity. Laraine Newman came from The Groundlings. Garrett Morris was a classically trained singer and playwright who often felt out of place in the white-dominated comedy room. And Chevy Chase? He was the break-out star, the one who looked like a traditional leading man but acted like a slapstick anarchist.

👉 See also: New Movies in Theatre: What Most People Get Wrong About This Month's Picks

The chemistry was volatile. Honestly, it’s a miracle they didn't kill each other. They lived in the office. They worked until 4 a.m. They did things that would get a modern HR department dissolved in minutes. But that pressure cooker created something authentic.

The Sketches That Defined 1975 Saturday Night Live

The "Wolverines" sketch was the first thing people saw. Michael O'Donoghue playing a linguistic tutor and John Belushi as his student. It was quiet. It was strange. It ended with the tutor dropping dead and Belushi mimicking his death. It told the audience: Don't expect a punchline. Expect the unexpected.

Then there was Weekend Update.

Chevy Chase would sit at the desk, pretending to be a serious journalist, and say, "I'm Chevy Chase, and you're not." It sounds arrogant now, but in 1975, it was a revolution. It mocked the very idea of the "trusted newsman" during an era where trust in the government was at an all-time low post-Watergate.

- The Killer Bees: The cast hated the costumes. Lorne Michaels kept pushing them because he liked the absurdity. Eventually, it became a recurring bit because the audience loved seeing serious actors like Rob Reiner (the first guest to wear the suit) look ridiculous.

- The Muppets: As mentioned, these were a disaster. They represented the last gasp of the "old" variety show format trying to merge with the "new" SNL. By the end of the first season, they were gone.

- Albert Brooks: He contributed short films. This was the precursor to the SNL Digital Shorts or the Please Don't Destroy videos we see now. In 1975, putting a pre-recorded film in a "live" show was seen as cheating by some, but it added a cinematic layer the show desperately needed.

The Cultural Context You've Probably Forgotten

You have to remember what 1975 looked like. The Vietnam War had just ended. Nixon was gone. The "Summer of Love" was a distant, hungover memory. People were cynical. TV was mostly The Lawrence Welk Show or Hee Haw. There was no internet. No cable. No YouTube.

If you were young and wanted to see someone talk the way you talked, you had to stay up late on a Saturday night. 1975 Saturday Night Live was the only place where the counter-culture wasn't being mocked; it was being made.

✨ Don't miss: A Simple Favor Blake Lively: Why Emily Nelson Is Still the Ultimate Screen Mystery

The show was dangerous because it was live. Anything could happen. When Richard Pryor hosted later in the first season, the tension was so high that NBC insisted on a five-second delay. It was the first time they ever used one. The legendary "Word Association" sketch between Pryor and Chase is still used in college sociology classes today to discuss racial tension. It was raw. It was uncomfortable. It was brilliant.

The Chevy Chase Problem

Chevy was the first one to realize he was bigger than the show. He was on the cover of New York magazine after just a few months. His "Weekend Update" persona made him a household name. But his quick rise caused massive friction within the cast. They were supposed to be a troupe. An ensemble.

He left after the first season (well, early in the second) to go to Hollywood. It was a betrayal to many of the others. But his departure proved the format was stronger than any one person. When Bill Murray joined to replace him, the show didn't die—it evolved.

The Writers’ Room: A Den of Iniquity

If you think the cast was wild, the writers were worse. Herb Sargent, Tom Schiller, Anne Beatts, Rosie Shuster, and the late, great Michael O'Donoghue. They weren't "TV writers." They were novelists, National Lampoon alums, and poets.

They didn't write "jokes." They wrote satirical attacks.

The atmosphere was fueled by coffee, cigarettes, and various substances that were common in the mid-70s. It wasn't about "finding the funny." It was about surviving the week. Lorne Michaels acted as the buffer between the suits at 30 Rock and the "children" in the writers' room. He protected them. He let them be weird. Without that protection, SNL would have been canceled after episode three.

🔗 Read more: The A Wrinkle in Time Cast: Why This Massive Star Power Didn't Save the Movie

Fact-Checking the "Golden Age"

People often say the 1975 Saturday Night Live era was the only "good" era. That’s a lie.

There were huge chunks of those early episodes that were boring. Long, rambling musical performances. Sketches that went on for twelve minutes and didn't have an ending. The Muppets were, objectively, a drag. But the peaks were so high that we forget the valleys. We remember the lightning, not the clouds.

How to Watch It Today Without Getting Bored

If you go back and watch the full episodes on Peacock or DVD, don't expect the pacing of a modern sitcom. It’s slow. It breathes.

- Watch the Richard Pryor episode (S1, E7). It is arguably the most important hour of television in the 1970s.

- Look for the commercial parodies. They were so well-made that many viewers at home thought they were real products. "New Improved Don’t Feel Like Cooking Tonight" or the "Three-Mile Island" jokes.

- Pay attention to Gilda Radner. Her physicality was decades ahead of its time. She didn't need a script to be the funniest person in the room.

The Actionable Legacy of 1975

The biggest takeaway from the 1975 season isn't the comedy—it's the audacity. They didn't wait for permission to be different. They just were.

If you’re a creator or a fan today, here’s how to apply the 1975 SNL ethos:

- Embrace the "Live" Aspect of Life: Perfection is the enemy of authenticity. The reason SNL worked was because it was messy. In an era of filtered Instagram feeds and AI-generated scripts, humans crave the "glitch."

- Build an Ensemble, Not a Solo Act: The best moments of the first season happened when the cast fed off each other's energy. Find your "troupe."

- Poke the Bear: The show was at its best when it was making the network nervous. If you aren't making someone a little uncomfortable, you probably aren't saying anything new.

The 1975 Saturday Night Live wasn't just a TV show. It was a cultural earthquake. It told a generation of people who felt ignored by the mainstream that they finally had a home, even if it was only for 90 minutes on a Saturday night. It proved that if you give smart, angry, funny people a microphone and a deadline, you can change the world—or at least make it a whole lot funnier.

Go watch the "Word Association" sketch again. Watch the "Bass-O-Matic." Realize that these were people making it up as they went along. That’s the magic. There was no blueprint. There was just a red "ON AIR" light and a lot of nerve.