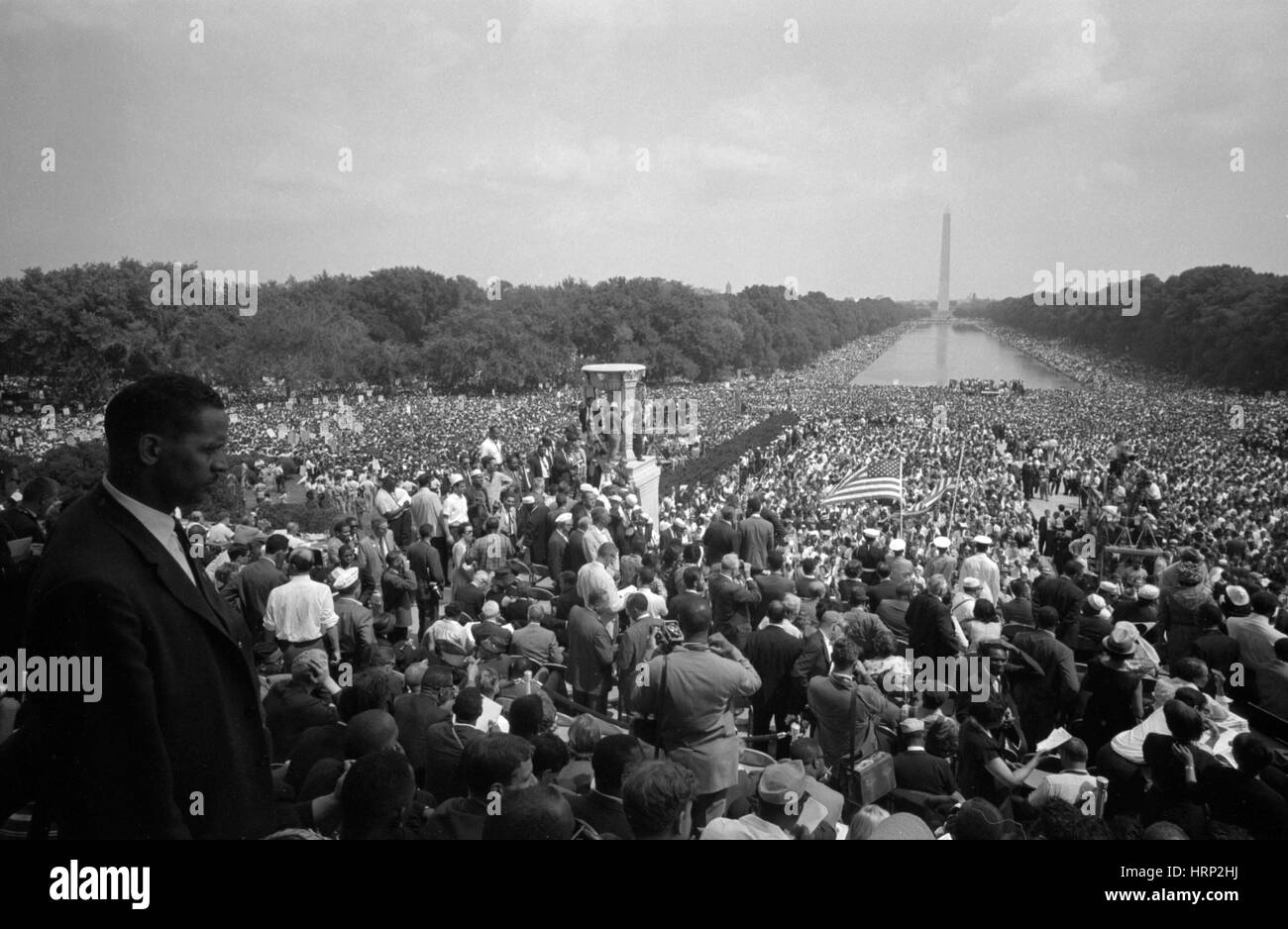

It’s easy to look back at the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom as a grainy, black-and-white moment in a history textbook. We all know the "I Have a Dream" speech. Most of us can picture the massive crowds stretching from the Lincoln Memorial to the Washington Monument. But honestly, most people get the "why" and the "how" of that day completely wrong. It wasn't just a polite gathering for civil rights. It was a massive, logistical nightmare that nearly didn't happen, organized by a man the government was terrified of, and it wasn't just about "sitting at the lunch counter."

It was about money. It was about labor. It was about the fact that you can’t have freedom if you can’t afford to eat.

The Architect Nobody Mentions

Everyone remembers Dr. King. He was the voice. But the actual brain behind the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom was Bayard Rustin. Rustin was a brilliant, openly gay (at a time when that was a legal and social death sentence), former communist organizer who basically had to stay in the shadows because he was "too controversial" for the mainstream movement.

He had seven weeks.

Just seven weeks to coordinate 250,000 people. He had to figure out how to get thousands of buses into D.C., where they would park, how to feed everyone (they made 80,000 cheese sandwiches because they wouldn't spoil in the heat), and how to keep the peace without a visible police presence that might spark a riot. He even organized "The Guardians," a volunteer security force made up of black off-duty police officers and firemen. It was a masterpiece of logistics.

💡 You might also like: Daniel Blank New Castle PA: The Tragic Story and the Name Confusion

What the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom Was Really Demanding

We call it "The March on Washington" for short, but the full title—the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom—is the part that matters. The "Jobs" part often gets scrubbed from the narrative. The organizers weren't just asking for an end to segregation; they were asking for a $2.00 minimum wage. That sounds like nothing now, but in 1963, that was roughly $19.00 an hour in today's money. They were demanding a massive federal works program and an end to workplace discrimination.

The Kennedy administration was actually terrified of the march. JFK tried to talk the "Big Six" leaders out of it. He thought it would turn violent and kill the civil rights bill he was trying to push through Congress. When they refused to cancel it, the government went into overdrive. They banned liquor sales in D.C. for the first time since Prohibition. They called in 19,000 troops to stand by in the suburbs. They even pre-drafted a declaration of martial law.

The Speech That Wasn't Supposed to Happen

John Lewis, who was just 23 at the time and representing the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), had a speech that was so radical the other leaders made him change it at the last minute. He was going to ask, "Which side is the federal government on?" and mention "scorched earth" policies. They literally made him rewrite parts of it in the back of the Lincoln Memorial while the program was already running.

And then there’s King’s speech. The "I Have a Dream" part? He wasn't even going to say it. He had used that metaphor before in Detroit, and his advisers told him it was cliché. He was sticking to his prepared text until Mahalia Jackson, the legendary gospel singer, yelled out from behind him, "Tell 'em about the dream, Martin!"

📖 Related: Clayton County News: What Most People Get Wrong About the Gateway to the World

He put his notes aside. He shifted gears. The rest is history.

The Logistics of 250,000 People in 1963

Imagine trying to organize a quarter of a million people without a cell phone, without the internet, and without a centralized mailing list. You're using rotary phones and mimeograph machines.

The sheer scale was insane.

- The "Freedom Trains": Special trains were chartered from all over the country.

- The Buses: Over 2,000 buses rolled into the capital.

- The Sound System: Rustin knew that if people in the back couldn't hear, they would get restless. He spent a massive chunk of the budget on the most advanced sound system available at the time. Legend has it the FBI actually tampered with it, and Rustin had to get it fixed right before the first speaker took the stage.

It’s also worth noting who wasn't allowed to speak. Despite the fact that women like Dorothy Height and Ella Baker were the backbone of the movement, not a single woman was invited to give a full-length speech that day. They were relegated to a "Tribute to Women" section that lasted just a few minutes. It’s a reminder that even within a movement for equality, there were deep, systemic blind spots.

👉 See also: Charlie Kirk Shooting Investigation: What Really Happened at UVU

The Immediate Aftermath and the FBI

If you think the march was universally loved, you're wrong. A Gallup poll taken shortly after the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom showed that a majority of Americans felt the march was "un-American" or would hurt the cause of civil rights.

The FBI’s response was even more chilling. Two days after the march, William Sullivan, the head of the FBI’s Intelligence Division, wrote a memo stating: "In the light of King’s powerful demagogic speech yesterday... he stands head and shoulders above all other Negro leaders... We must mark him now, if we have not done so before, as the most dangerous Negro of the future in this Nation."

That march is what triggered the intense, illegal surveillance of Dr. King. It wasn't a "feel-good" moment for the people in power; it was a threat.

Actionable Insights: Learning from the March

To understand the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom is to understand that progress isn't an accident. It’s a grind. If you’re looking to apply the lessons of 1963 to modern advocacy or even professional leadership, here’s the reality:

- Logistics are as important as vision. You can have the greatest "dream" in the world, but if the "buses" don't show up and the "sound system" fails, no one hears you. Rustin’s meticulous planning is why the march succeeded.

- Economic justice is inseparable from social justice. The marchers weren't just looking for dignity; they were looking for a paycheck. Any movement that ignores the material needs of people usually fails to gain long-term traction.

- Radicalism is often edited by history. We remember the "dream," but we forget the "demand." Don't let the polished, comfortable version of history prevent you from seeing the disruptive, uncomfortable work that actually creates change.

- Coalitions are messy. The leaders of the "Big Six" didn't always like each other. They had different philosophies and different egos. They moved forward anyway because the goal was bigger than their friction.

To truly honor the legacy of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, one must look past the statues and the quotes on Instagram. Look at the list of demands they carried on their placards. Many of them—like full employment and a living wage—remain unfulfilled. The march wasn't a finish line; it was a massive, high-stakes opening move in a game that is still being played.

Start by reading the full text of the "10 Demands" from the original 1963 program. Compare them to the current economic landscape. You’ll find that the "Jobs" part of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom is still the most radical and unfinished part of the story.