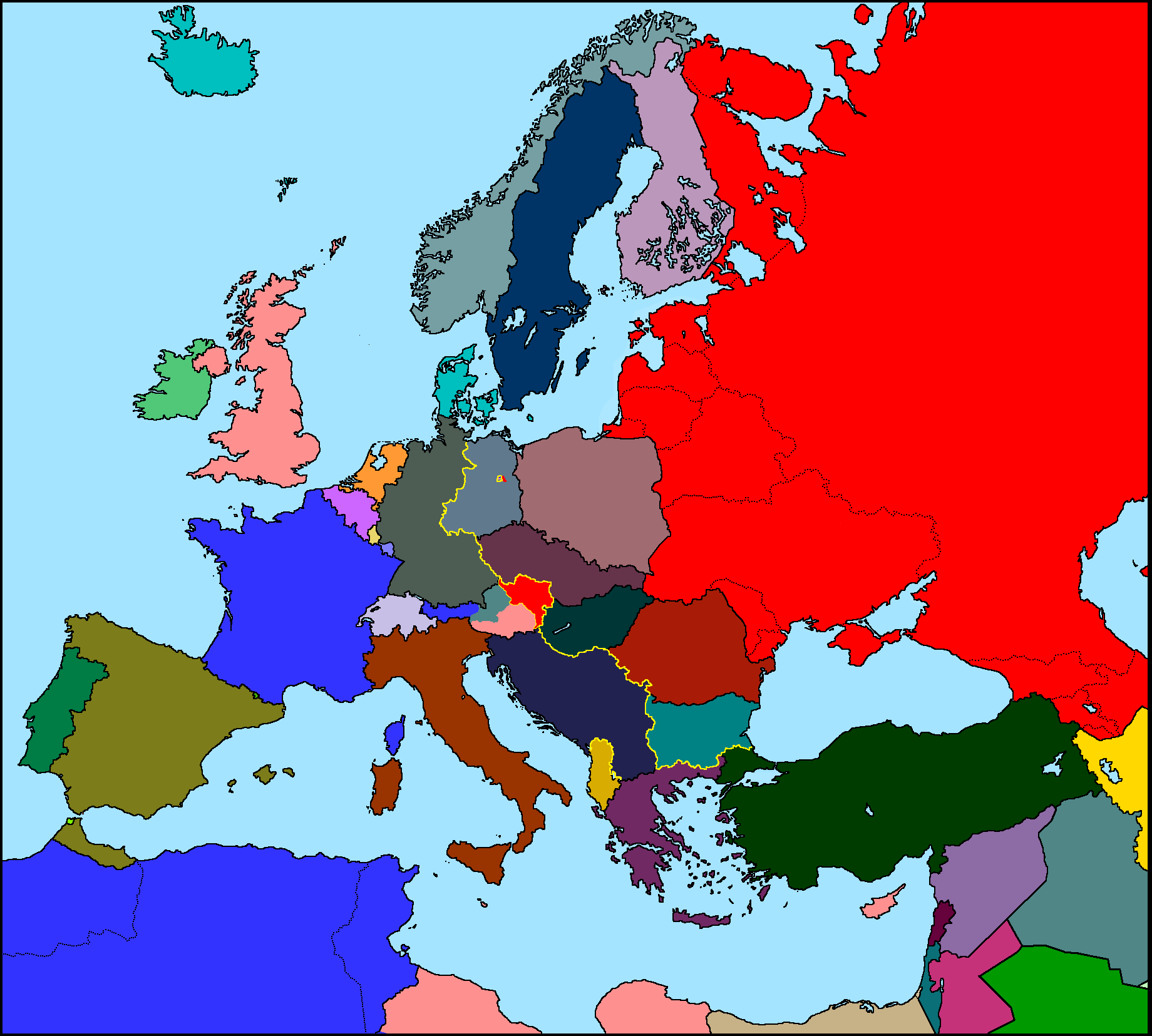

Five years after the guns fell silent. That’s where we are. If you look at a 1950 map of Europe, you aren't just looking at geography; you’re looking at a continent-sized crime scene where the chalk outlines were still being drawn. It’s messy. Honestly, it’s a miracle the borders even stayed still long enough for cartographers to print them.

Most people think the end of WWII in 1945 fixed everything. It didn’t. Between 1945 and 1950, Europe was a shifting jigsaw puzzle of "spheres of influence" and military occupations. By 1950, the glue was finally drying, but the shape was unrecognizable to anyone who had lived through the 1930s. Germany was effectively gone, replaced by a pair of bitter siblings. Poland had literally physically moved. The Baltics had vanished into a red mist.

The Year the Iron Curtain Hardened

1950 is a specific, weirdly quiet moment. The Berlin Airlift had ended the year before. NATO was barely a year old. The Warsaw Pact hadn't even been signed yet—that wouldn't happen until '55—but everyone knew which side of the fence they were on.

Look at the center of the map. Germany is the gaping wound. By 1950, the 1950 map of Europe shows a clear, jagged line splitting the country. You had the Federal Republic of Germany (West) and the German Democratic Republic (East). But it wasn't just a line. It was a complete socio-economic amputation.

What’s wild is that many maps from this specific year still showed "pre-war" borders as dotted lines. Cartographers in the West were often hesitant to admit that the Soviet Union had permanently swallowed parts of East Prussia. They held onto the hope of a return to 1937 borders. It was a lie, of course. Stalin had already moved the Soviet border West, and in turn, pushed Poland’s border West to the Oder-Neisse line.

📖 Related: London to Canterbury Train: What Most People Get Wrong About the Trip

Poland literally slid across the map. It lost its eastern territories (Kresy) to the USSR and gained "Recovered Territories" from Germany in the west. If you compared a 1939 map to a 1950 map of Europe, Poland looks like it’s been nudged by a giant thumb.

The Vanishing Acts

You won’t see Estonia, Latvia, or Lithuania on a 1950 map. Well, you might see the names, but they’ll be labeled as "Soviet Socialist Republics." To the United States and much of the West, this was a "non-recognition" policy. They kept the embassies of the old Baltic states open in Washington D.C., but on the actual ground? They were gone. Inside the USSR.

Then there’s the Free Territory of Trieste. Ever heard of it?

Probably not.

But in 1950, it was a tiny, independent city-state between Italy and Yugoslavia. It existed because nobody could agree on who should own it. It was a UN-mandated "free territory" that didn't officially get resolved until 1954. It’s one of those weird little anomalies that makes 1950 such a fascinating year for map nerds.

Why the Borders Moved (And Why It Matters Now)

The 1950 map of Europe wasn't just about winning a war. It was about ethnic cleansing on a scale we rarely talk about. Millions of Germans were expelled from Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Hungary. Millions of Poles were moved from the East. The map looks "cleaner" in 1950 because the diverse, multi-ethnic patches of Central Europe had been violently homogenized.

👉 See also: Things to do in Hanover PA: Why This Snack Capital is More Than Just Pretzels

Basically, the borders were drawn to match the people, but only after the people had been forced to move to match the borders.

- The Saar Protectorate: Look at the border between France and West Germany. There’s a little blob called the Saar. In 1950, it wasn't part of Germany. It was a French protectorate with its own postage stamps and its own national football team. It didn't "re-join" Germany until 1957.

- The Kaliningrad Enclave: That little piece of Russia that sits between Poland and Lithuania today? In 1950, it was being rapidly "Sovietized." The old German city of Königsberg had been renamed Kaliningrad in 1946. By 1950, the German population was almost entirely gone, replaced by Soviet settlers.

The Mediterranean was a different world

Italy had lost its colonies. On a 1950 map of Europe, you can see Italy trying to redefine itself as a republic after the monarchy was kicked out in '46. To the east, Greece was just emerging from a brutal civil war that had threatened to turn it communist. The 1950 map shows Greece firmly in the Western camp, a key piece of the "containment" strategy against the USSR.

And then there's Yugoslavia.

Tito had broken with Stalin in 1948.

By 1950, Yugoslavia was this weird, "non-aligned" communist state. It sat on the map like a massive roadblock to Soviet ambitions in the Balkans. It was the only communist country on the 1950 map that was actually taking aid from the Americans. Think about how crazy that is.

The Ghost of the Austro-Hungarian Empire

Even in 1950, you could still see the "skeleton" of the old empires. The borders of Czechoslovakia and Hungary still followed lines that had been debated at the end of World War I. But the 1950 map added a new layer: the "Cordon Sanitaire" in reverse. Instead of a buffer against Russia, these states were now the "Satellite States."

✨ Don't miss: Hotels Near University of Texas Arlington: What Most People Get Wrong

Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, Albania, and Czechoslovakia. On paper, they were sovereign. On the 1950 map of Europe, they were colored differently. But in reality, their capitals were controlled via telephone from the Kremlin.

The complexity here is that 1950 was the last year of "true" post-war flux. By 1951, the Schuman Declaration would start the process that eventually became the European Union. But in 1950? It was all about coal, steel, and keeping the Russians out, the Americans in, and the Germans down. That's a famous quote by Lord Ismay, the first Secretary General of NATO, and it perfectly summarizes the geography of the era.

How to use this knowledge

If you’re a collector or a history buff looking at a 1950 map of Europe, don't just look at the country names. Look at the "Occupation Zones" in Austria. Yes, Austria was occupied just like Germany until 1955. Vienna was split into four sectors, just like Berlin. If your map shows Austria as a single, unified color, it’s a "political" map, not a "military" one.

Actionable Steps for Researchers and Collectors:

- Check the German Borders: If the map shows "Silesia" or "Pomerania" as part of Germany, it’s likely a West German-produced map from 1950 that refused to recognize the new reality. These are "revanchist" maps and are highly collectible.

- Look for the "Free Territory of Trieste": This is the ultimate "litmus test" for map accuracy in 1950. If it’s just marked as Italy or Yugoslavia, the map is simplified.

- Identify the Saar: If the Saarland is shaded the same as West Germany, the map is technically "incorrect" for the year 1950.

- Analyze the Baltic States: See if they are listed as "Independent" (rare in 1950), "Occupied," or "Soviet Republics." This tells you the political bias of the mapmaker.

- Examine the Polish Curzon Line: Compare the eastern border of Poland to the 1939 version. The "loss" of Lviv (Lwów) to the Ukrainian SSR is the definitive marker of the 1950 territorial shift.

The 1950 map is a snapshot of a world that had finished burning and was just starting to rebuild. It represents the moment the "West" and "East" became more than just cardinal directions—they became identities that would define the next four decades of human history.