If you look at a 1930 map of Middle East borders, you aren't just looking at geography. You’re looking at a crime scene. Or maybe a blueprint. It depends on who you ask, honestly. By 1930, the dust from World War I had mostly settled, but the "peace" it created was anything but peaceful. The Ottoman Empire was a memory, replaced by a patchwork of mandates, fledgling kingdoms, and lines drawn in the sand by men in London and Paris who had never even visited the deserts they were carving up.

It’s messy.

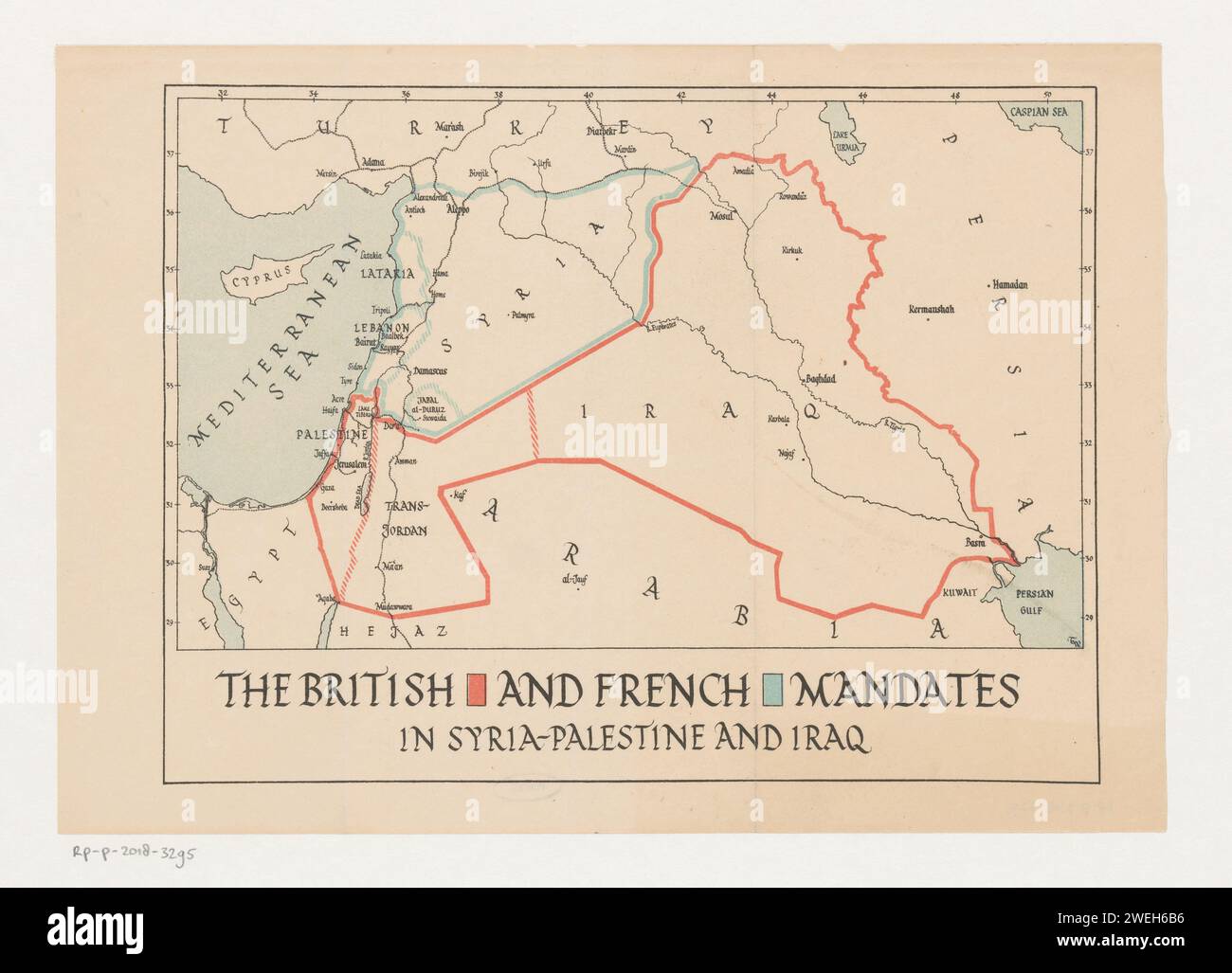

Back then, the world was transitionary. We often think of the Middle East as this ancient, static place, but the 1930s version of it was brand new. It was experimental. You had the British Empire holding the strings in places like Iraq and Palestine, while the French were trying to manage a very rebellious Syria and Lebanon. If you compare a map from 1910 to one from 1930, the difference is jarring. The 1930 map shows the birth of the modern nation-state in a region that, for centuries, had lived under imperial or tribal logic.

The colonial "pencil" and the 1930 map of Middle East mandates

Most people talk about the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916 as the start of the trouble, and they aren't wrong. But by 1930, those secret deals had become physical reality. The 1930 map of Middle East territories shows the League of Nations Mandates in full swing. This wasn't "colonization" in the old-school sense—at least not on paper. The Mandate system was supposed to be a "tutelage" period. The idea was that the "advanced" European powers would help these "developing" nations learn how to run a modern state.

Total nonsense, right?

In reality, it was a way for Britain and France to keep the oil flowing and the strategic routes to India open without calling it an empire. In 1930, Iraq was right on the edge of "independence." The Anglo-Iraqi Treaty was signed that year. It looked like freedom, but it basically gave the British military the right to stay there indefinitely. If you look at the Iraqi border on a 1930 map, you see that weird, straight line in the south and west. Those lines ignored the migration patterns of the Shammar and Anizah tribes. When you force a nomadic people to respect a hard border drawn by a guy named Sir Percy Cox, you’re asking for a century of friction.

The French were having an even harder time. By 1930, the State of Syria was a pressure cooker. The French had tried to divide the region into smaller states—an Alawite state, a Druze state, the State of Aleppo—basically a "divide and rule" strategy. It failed. By 1930, they had to start lumping them back together because the locals were making it impossible to govern. You see this on the maps of the era; the labels keep shifting as the French tried to figure out how to keep the lid on Syrian nationalism.

🔗 Read more: When is the Next Hurricane Coming 2024: What Most People Get Wrong

Strange borders and the birth of Saudi Arabia

Something else stands out on a 1930 map of Middle East geography: the massive, shifting space in the center of the Arabian Peninsula. While the British and French were playing Risk in the north, Ibn Saud was busy smashing rivals in the south.

1930 was a pivotal year for what would become Saudi Arabia.

Just a year or two before, the Ikhwan Revolt—a massive internal rebellion by Ibn Saud’s own religious militia—had been crushed. By 1930, the map was starting to solidify into the shape we recognize today. However, the borders with Yemen and what is now the UAE were basically "vague suggestions." There was no "Empty Quarter" border because no one thought the sand was worth fighting over yet. They hadn't found the massive oil deposits in the Eastern Province yet—that wouldn't happen for another few years.

Imagine that. A map where the most valuable resource on earth is a total secret.

The 1930 map also shows the Kingdom of Hejaz and Nejd. It wasn't even called "Saudi Arabia" yet; that name didn't stick until 1932. If you find an original map from 1930, you'll see the British influence creeping in from the edges. The Trucial States (now the UAE), Qatar, and Kuwait were all "Protectorates." They were small, coastal hubs that Britain used as coaling stations for ships. They looked insignificant on a 1930 map. Today, they are global financial titans.

The Palestine Mandate and the 1930 turning point

You cannot talk about a 1930 map of Middle East history without looking at the British Mandate for Palestine. This is where the map gets incredibly heavy with historical weight. By 1930, the tensions between the Jewish Zionist settlers and the Arab population had reached a boiling point. The 1929 riots had just happened.

💡 You might also like: What Really Happened With Trump Revoking Mayorkas Secret Service Protection

In response, the British issued the Hope-Simpson Enquiry and the Passfield White Paper in 1930.

These documents recommended limiting Jewish immigration and land purchase. If you look at a map of land ownership in Palestine from 1930, it’s a mosaic. It doesn't look like the modern "green line" or the West Bank/Gaza split. It was a singular unit governed from Jerusalem by a British High Commissioner. To the east, Transjordan (modern-day Jordan) was also under British control, but it was being run as a separate Emirate under Abdullah I. The 1930 map shows Transjordan as a massive, mostly empty buffer zone between the chaos of Palestine and the growing power of the Saudi state.

Why 1930 matters more than 1920 or 1945

- Iraq's "Independence" Illusion: 1930 was the year Iraq signed the treaty that supposedly ended the Mandate, setting the template for "client states" in the region.

- The French Failure: By 1930, it was clear the French "divide and rule" tactic in Lebanon and Syria was creating a sectarian ghost that would haunt those countries for the next 90 years.

- The Calm Before the Oil: This was the last year the Middle East was mapped primarily for its routes rather than its resources. Once oil was struck in Bahrain (1932) and Saudi Arabia (1938), the maps became much more aggressive.

- The End of the Caliphate Era: By 1930, the Republic of Turkey (under Atatürk) had fully pivoted toward Europe. The 1930 map shows Turkey with its modern borders, having finally given up its claims to the Arab lands of the old empire.

The cartography of "unintended consequences"

Looking at these maps today feels like reading a tragedy. You see the "Wadi Sirhan" panhandle in Jordan—that weird "V" shape that jabs into Saudi Arabia. Legend says it’s there because Winston Churchill had a "hiccup" while drawing the line after a long lunch, but the reality is more boring: it was a strategic corridor to keep a land route open between Cairo and Baghdad.

These maps are full of those little "logical" decisions that turned into permanent geopolitical scars.

The 1930 map of Middle East regions also shows the prominence of the railway. The Hejaz Railway, though partially destroyed during the war, was still a major feature. In 1930, people still thought of the region in terms of train tracks and ports. They didn't see the world through the lens of flight paths or fiber optic cables. The port of Haifa was being transformed by the British into a major Mediterranean hub, intended to be the outlet for Iraqi oil.

It's also worth noting what isn't on the map. There is no "Israel." There is no "United Arab Emirates." There is no "Islamic State." There are just "Administrations" and "Territories."

📖 Related: Franklin D Roosevelt Civil Rights Record: Why It Is Way More Complicated Than You Think

How to use a 1930 map for actual research

If you're a student or a history buff trying to use a 1930 map of Middle East borders for a project, you have to be careful with your sources. Maps from this era were often propaganda. A British map will show the Mandates as stable and orderly. A French map might exaggerate the "autonomy" of the Alawite State.

The best way to analyze these is to look at the "Limit of Cultivation" lines. In 1930, where the rain stopped was where the government stopped. Beyond the "sown" land was the "desert," and the desert was governed by tribal law, no matter what the map-makers in London said.

Actionable Insights for Historians and Travelers

- Cross-Reference with the Red Line Agreement: If you want to understand why borders look the way they do on a 1930 map, look up the "Red Line Agreement" of 1928. It shows how oil companies literally drew a red line around the old Ottoman Empire to divide the oil rights. The map followed the money.

- Look for "Old Names": You'll see "Constantinople" often still used interchangeably with "Istanbul" in Western maps of 1930, even though the name officially changed that year.

- Identify the "Neutral Zones": On a 1930 map of Middle East borders, look for the Saudi-Iraqi Neutral Zone and the Saudi-Kuwaiti Neutral Zone. These were "diamond-shaped" areas where sovereignty was shared. They existed until the 1970s and 80s!

- Study the Railroads: To understand 1930s power, follow the tracks. The completion of the Baghdad Railway was the "internet" of its day.

The 1930 map of Middle East history is a snapshot of a world caught between an imperial past and a nationalistic future. It was a time when the British thought they would stay forever, and the local populations were just starting to realize they had the power to push back. Every time you see a modern border dispute in the Levant or the Persian Gulf, you're usually seeing an argument about a line that was first scratched onto a map around 1930.

To truly understand the region, stop looking at the 2026 map for a second. Go back to 1930. Look at the "Mandates." Look at the "Protectorates." Look at the straight lines drawn through the middle of tribal grazing lands. Once you see the "logic" of 1930, the chaos of the present starts to make a lot more sense.

If you're looking to purchase or view high-quality reprints of these maps, focus on archives like the David Rumsey Map Collection or the Library of Congress. They hold the original British War Office maps that show the minute details of these 1930 surveys, including water wells and camel tracks that were more important to the locals than the "official" borders. Using these primary sources prevents the common mistake of relying on modern "recreations" that often scrub out the messy, overlapping claims of the 1930s.