You’ve probably seen it. A glowing, circular disc of light, swirling with oranges and purples, looking like a cosmic marble floating in a dark room. People post it on social media with captions about how "insignificant" we are. It’s usually labeled as a picture of the entire universe.

But here’s the thing. It’s not a photograph.

If you tried to take an actual photo of the universe, you’d fail. Miserably. You’re inside it, for one. It’s like trying to take a photo of the exterior of your house while you’re locked in the basement with no windows. When we talk about a picture of the entire universe, we are actually talking about data visualization, mathematical projections, and the physical limit of how far light can travel before it just... stops being light.

The Map That Everyone Mistakes for a Photo

Most people are actually looking at the Logarithmic Map of the Universe created by Pablo Carlos Budassi.

Budassi isn't a NASA satellite. He’s an artist and musician. Back in 2012, while he was making hexaflexagons for his son's birthday, he had a "eureka" moment about visualizing the scale of the cosmos. He used maps produced by researchers at Princeton University—specifically the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS)—and combined them with NASA imagery.

The SDSS is basically the most ambitious census of the sky ever attempted. It used a 2.5-meter wide-angle optical telescope at Apache Point Observatory in New Mexico. Over years, it mapped more than 35% of the sky, capturing hundreds of millions of objects.

Budassi took those data points and squashed them.

He used a logarithmic scale. In a normal map, an inch represents a fixed distance—say, a mile. In a logarithmic map, each inch represents a distance that increases by a factor of ten. The center of the image is our Sun. As you move outward, the scale explodes. You pass the Oort Cloud, then the Alpha Centauri system, then the Milky Way, until the very edge of the circle shows the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB).

It’s a masterpiece of data compression. But it's not what the universe "looks like" from a distance. There is no "distance" outside the universe to look from.

📖 Related: Dyson V8 Absolute Explained: Why People Still Buy This "Old" Vacuum in 2026

The Real "Oldest" Picture of the Entire Universe

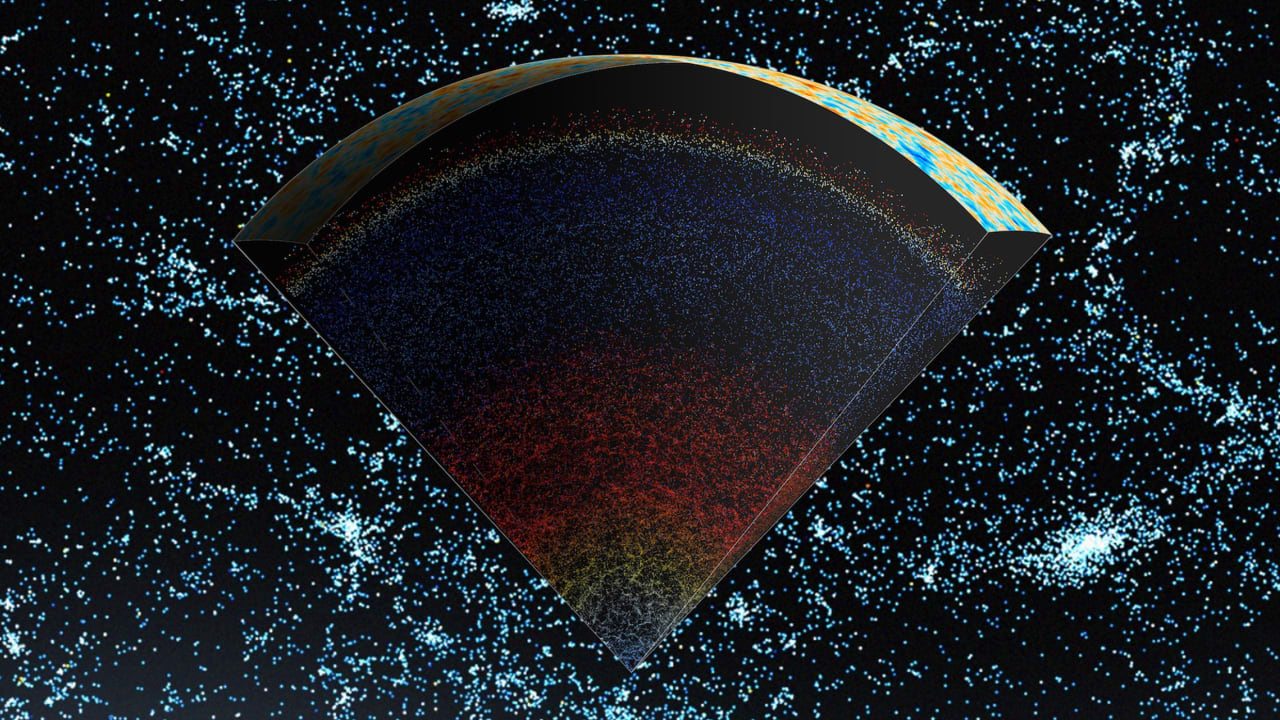

If you want the real deal—the closest thing scientists have to a physical "snapshot" of the cosmos—you have to look at the Planck Mission's 2013 data release.

This is the Cosmic Microwave Background radiation.

When the universe was very young, it was a hot, dense soup of plasma. It was opaque. Light couldn't travel anywhere because it kept bumping into electrons. About 380,000 years after the Big Bang, the universe cooled down enough for atoms to form. Suddenly, the "fog" cleared. The light that was trapped was finally free to move.

That light is still traveling.

Because the universe has been expanding for 13.8 billion years, that light has been stretched. It’s no longer visible to the human eye. It’s been "redshifted" all the way into the microwave part of the spectrum. When the Planck satellite (and WMAP before it) scanned the sky, it captured this "afterglow."

Basically, the CMB is a picture of the entire universe when it was a toddler. Those little splotches of blue and orange aren't stars. They are tiny fluctuations in temperature. These fluctuations are the seeds of everything. The slightly denser spots eventually collapsed under gravity to form galaxies, stars, and eventually, us.

It's the ultimate baby photo.

The Problem With the "Edge"

We often see these pictures as a sphere. A bubble. This leads to a massive misconception: that the universe has an edge you could fly to and hit like a wall.

👉 See also: Uncle Bob Clean Architecture: Why Your Project Is Probably a Mess (And How to Fix It)

That’s probably wrong.

Cosmologists like Sean Carroll or Katie Mack often point out that we only see the Observable Universe. Because the universe has a finite age, and light has a speed limit ($c \approx 3 \times 10^8$ m/s), we can only see light that has had enough time to reach us.

Imagine you’re in a forest at night with a flashlight. You can see 50 feet in every direction. That 50-foot circle is your "observable" forest. It doesn’t mean the forest ends at 51 feet. It just means the light hasn't reached you from further out.

Every single picture of the entire universe we have is centered on us. If an alien were sitting in a galaxy 10 billion light-years away, their "picture" of the universe would look different. They would be the center of their own observable bubble.

Digital Art vs. Scientific Reality

We can't ignore the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST).

When the first "Deep Field" images came out, people lost their minds. And for good reason. But even those aren't pictures of the "entire" universe. They are tiny, tiny slivers. NASA likes to say that the first JWST deep field covered a patch of sky approximately the size of a grain of sand held at arm's length.

Within that "grain of sand," there are thousands of galaxies. Each galaxy has billions of stars. It's mind-boggling. But it’s still just a keyhole view.

The struggle for content creators and educators is balancing the "cool factor" with the "truth factor." Budassi’s logarithmic map is cool. It’s beautiful. It helps us understand where we fit in the hierarchy of scale. But it's a map, not a photograph.

✨ Don't miss: Lake House Computer Password: Why Your Vacation Rental Security is Probably Broken

Why We Keep Making These Pictures

Humans are visual creatures. We struggle with the concept of "infinite" or "expanding flat topology." We want to see the "whole."

The Laniakea Supercluster map is another famous example. It looks like a glowing feather or a nervous system. It represents 100,000 galaxies, including our own. Scientists like Brent Tully mapped the movement of galaxies to define this "watershed" of gravity.

Is it a picture of the entire universe? No. It’s a neighborhood map. Our local supercluster is just one of millions in the cosmic web.

The "Cosmic Web" itself is a theoretical model of how dark matter pulls gas and galaxies into long filaments. We see this in massive computer simulations like IllustrisTNG. These simulations are often used in documentaries as if they are real footage. They aren't. They are the result of supercomputers crunching the laws of physics to see how things should look.

How to Actually "See" the Universe Yourself

If you’re tired of looking at flattened circles and artist renders, there are ways to interact with the real data.

- The Celestia Project: This is free, open-source software that lets you fly through the universe in 3D. It uses real coordinates for stars and galaxies. You can zoom out from Earth until the Milky Way is just a dot.

- ESASky: This is a professional-grade web tool from the European Space Agency. It lets you browse the sky across different wavelengths (X-ray, Infrared, Gamma-ray). It’s the closest you’ll get to sitting at a researcher's desk.

- NASA’s Eyes on the Universe: An app that tracks every exoplanet and spacecraft in real-time.

The Actionable Truth

Next time you see a "picture of the entire universe" on your feed, look for the details.

If it’s a perfect circle with the Sun in the middle, it’s the Budassi Map. Use it to understand scale, but remember it's a projection.

If it’s an oval with speckled static, it’s the CMB. That’s the oldest "real" light we can detect.

If it looks like a web of glowing silk, it’s a Simulation. It shows us the skeleton of the universe—dark matter—which we can’t even see with our eyes.

Understanding the difference doesn't make the images less beautiful. Honestly, it makes them more impressive. We are a species of apes stuck on a wet rock, and we’ve figured out how to map things billions of light-years away using nothing but math and some very expensive mirrors.

To dig deeper, stop looking at static images and check out the Sloan Digital Sky Survey’s public database. You can browse through the actual "plates" of sky that they've been scanning for decades. It’s messy, it’s full of noise, and it’s much more honest than a polished Instagram graphic.

The universe isn't a marble. It's a history book written in light. We're just learning how to read the pages.