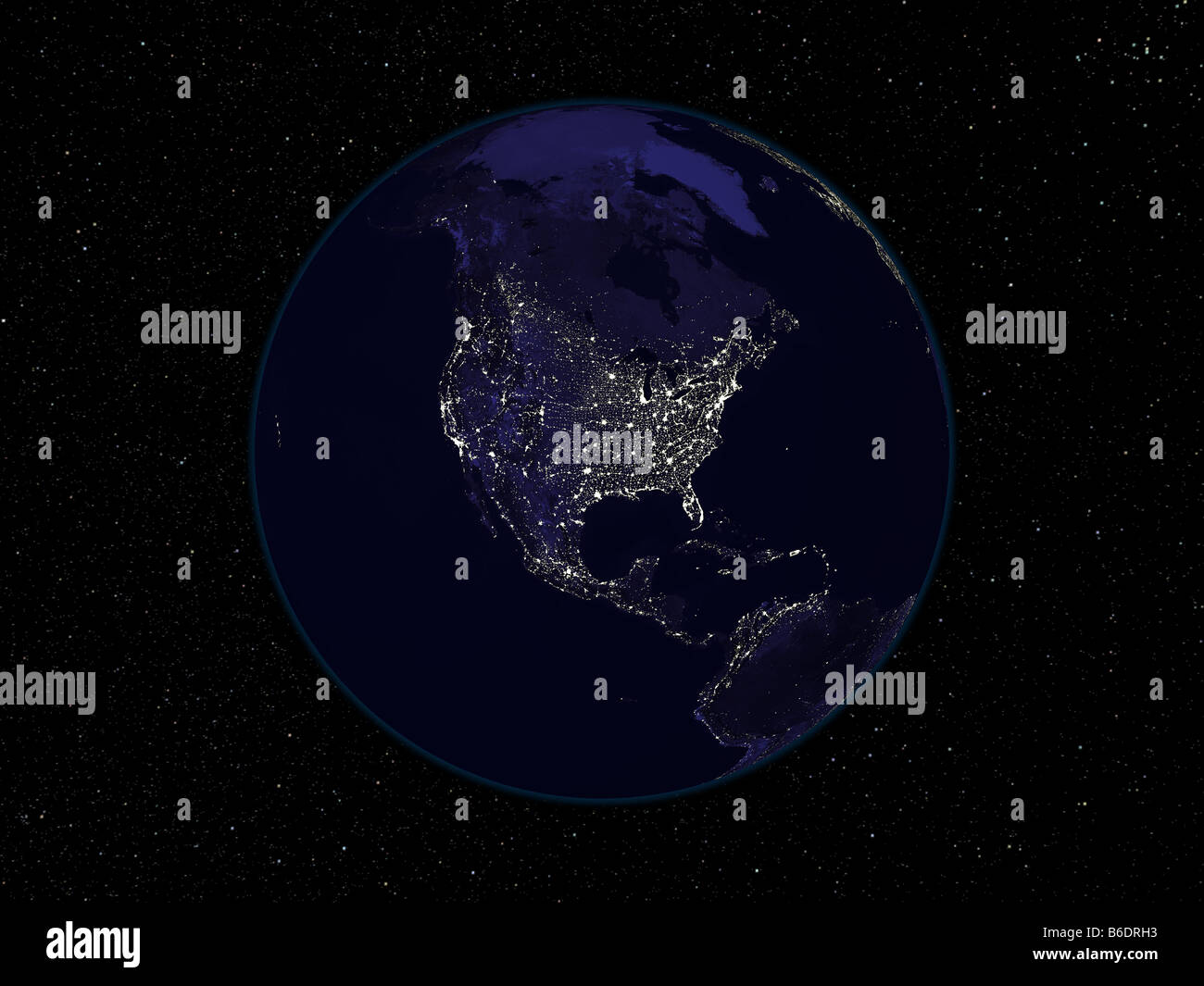

You’ve seen it. It’s everywhere. That glowing, electric spiderweb stretching from the Atlantic to the Pacific.

When you look at a satellite photo of United States at night, you aren't just looking at light bulbs. Honestly, you're looking at a heartbeat. It’s a literal visualization of where people live, where they work, and—most importantly—where they spend their money.

But here is the thing: a lot of those viral images you see on social media are actually fakes. Or at least, they’re highly manipulated "composite" images that don't look anything like what an astronaut sees from the cupola of the International Space Station (ISS). Real nighttime imagery is grainier, more nuanced, and tells a much deeper story about how the U.S. functions than a high-contrast wallpaper ever could.

The gear behind the glow

We didn't always have these crisp views. Back in the day, the Defense Meteorological Satellite Program (DMSP) gave us our first real look at the "Black Marble." But the sensors were... well, they were okay. They lacked the "dynamic range" to tell the difference between a bright stadium in Dallas and the general glow of the suburbs. Everything just kind of bled together into a white blob.

That changed with the Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership (Suomi NPP) satellite. It carries a piece of tech called the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite, or VIIRS.

VIIRS is a beast.

It has a "Day/Night Band" that is sensitive enough to detect the light from a single highway lamp or even a small boat in the middle of the ocean. It doesn't just take one photo; it sweeps the Earth in strips, and scientists at NASA and NOAA (the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) stitch those together to create the satellite photo of United States at night that we use for actual research.

What’s wild is that these sensors can "see" through thin clouds. They can distinguish between the blue-white of a modern LED streetlamp and the orange-ish hum of an old high-pressure sodium bulb. This isn't just for pretty pictures; it’s how we track urban sprawl.

Why the East and West look so different

If you draw a line straight down the middle of a satellite photo of United States at night, roughly along the 98th meridian, the country basically breaks in half.

The East is a chaotic, interconnected mess of light. The "Northeast Corridor"—that massive megalopolis stretching from Boston through New York, Philly, and down to D.C.—looks like one continuous glowing organism. It's dense. It's bright. It never stops.

Then you look West.

Suddenly, it’s dark.

👉 See also: DeWalt 18V Battery and Charger: Why the Old NiCad System Still Refuses to Die

Aside from the massive hubs like Chicago, Dallas, or Denver, the landscape is punctuated by tiny, lonely pinpricks of light. Most people assume this is just about population, but it's really about water and geography. The 98th meridian is roughly where the climate shifts from humid to arid. You can't have massive, sprawling cities without a massive water supply, so the "light map" of the U.S. is effectively a map of rainfall and irrigation.

Then you hit the West Coast, and it’s like a string of Christmas lights. Seattle, Portland, the Bay Area, and the massive, blinding sprawl of Los Angeles. Between those and the East? A whole lot of beautiful, necessary nothingness.

The "False" images vs. the real ones

Let’s talk about the "Blue Marble" versus the "Black Marble."

NASA released the Black Marble in 2012, and it broke the internet. But if you look at a satellite photo of United States at night on a stock photo site, it’s usually "color-enhanced." They turn the lights bright gold or neon blue. They add clouds that shouldn't be visible.

Real satellite data is actually monochromatic in its rawest form. Scientists often colorize it to make it easier for our human eyes to process, but the "true" view from space is much more subtle.

Astronauts often describe the lights of the U.S. as looking like "shattered diamonds on black velvet." If you look at photos taken by hand from the ISS, you see the atmosphere as a thin, green line—the "airglow"—sitting above the cities. You see the grid patterns of the Midwest, where every road was laid out by surveyors in perfect squares. It’s remarkably orderly compared to the tangled webs of older cities in Europe or even New England.

What we learn when the lights go out

This technology isn't just for staring at. It’s a tool for crisis.

When a hurricane hits the Gulf Coast, the first thing FEMA and researchers look at is the satellite photo of United States at night from the night before versus the night after. This "light shed" analysis shows exactly where the power grid has failed.

💡 You might also like: Denial of Service Attack: Why Your Site Just Stopped Working

Sometimes, the lights tell us about things we can't see during the day.

- Fracking and Oil: If you look at North Dakota in a night satellite image, there is a massive cluster of lights that looks like a major city. But there is no city there. That’s the Bakken shale formation. Those lights are actually gas flares—excess natural gas being burned off at oil well sites.

- Economic Downturns: During the 2008 recession, and more recently during the 2020 lockdowns, the "brightness" of the U.S. actually dimmed in certain sectors. Not because the streetlights were off, but because commercial activity—malls, office parks, factories—went dark.

- Light Pollution: Biologists use these photos to track how "skyglow" affects migratory birds. Many birds navigate by the stars, and the blinding glow of our cities acts like a giant confusing lighthouse that throws them off course.

The LED revolution is changing the view

If you compare a satellite photo of United States at night from 2010 to one from 2024, you’ll notice something weird. The color is shifting.

Cities are moving away from those old, amber-colored sodium lamps and installing LEDs. LEDs are cheaper and last longer, but they emit a lot of blue light. This is a bit of a nightmare for the VIIRS sensor on the Suomi NPP satellite, which isn't as sensitive to the blue end of the spectrum.

This means that, in some satellite images, a city might actually look dimmer than it used to, even though it’s technically brighter to the human eye. We are currently in a weird period where our eyes and our satellites don't agree on how bright the U.S. really is.

Newer satellites are being designed to fix this, but for now, it's a gap in the data that experts like Miguel Román at the Universities Space Research Association (USRA) are constantly trying to account for.

Using this data yourself

You don't need a PhD or a security clearance to look at this stuff. NASA makes a lot of it public through a tool called Worldview. You can literally go in, select the "Earth at Night" layer, and zoom into your own neighborhood.

It’s a humbling experience.

You see how your town fits into the larger puzzle. You see the dark gaps of the National Forests and the blinding intensity of the airports. You realize that "home" is just a tiny spark in a massive, interconnected electrical web.

👉 See also: Why Weather Radar Milton Florida Often Feels Like It's Lying to You

Actionable insights for the curious

If you want to dive deeper into nighttime imagery or use it for your own projects, here is how you actually do it:

- Check the NASA Black Marble site: This is the gold standard. They provide processed, high-definition global maps that remove the "noise" of moonlight and fire.

- Use the VIIRS Today portal: If you want to see what the U.S. looked like last night, this is the place. It’s updated daily. It’s great for tracking things like active wildfires or major power outages.

- Contribute to "Globe at Night": This is a citizen science project. You can help scientists ground-truth the satellite data by reporting how many stars you can see from your own backyard. It helps them calibrate the "light pollution" levels seen from space.

- Invest in a light pollution filter: If you’re an amateur astrophotographer inspired by these images, these filters can help you cut through the "city glow" shown in the satellite photos so you can actually see the stars from the ground.

Looking at a satellite photo of United States at night reminds us of two things at once: how much we’ve conquered the darkness, and how much of the natural world we lose in the process. It’s a map of our success, but also a map of our footprint. Next time you see one, look for the dark spots—that’s where the real wild America still lives.