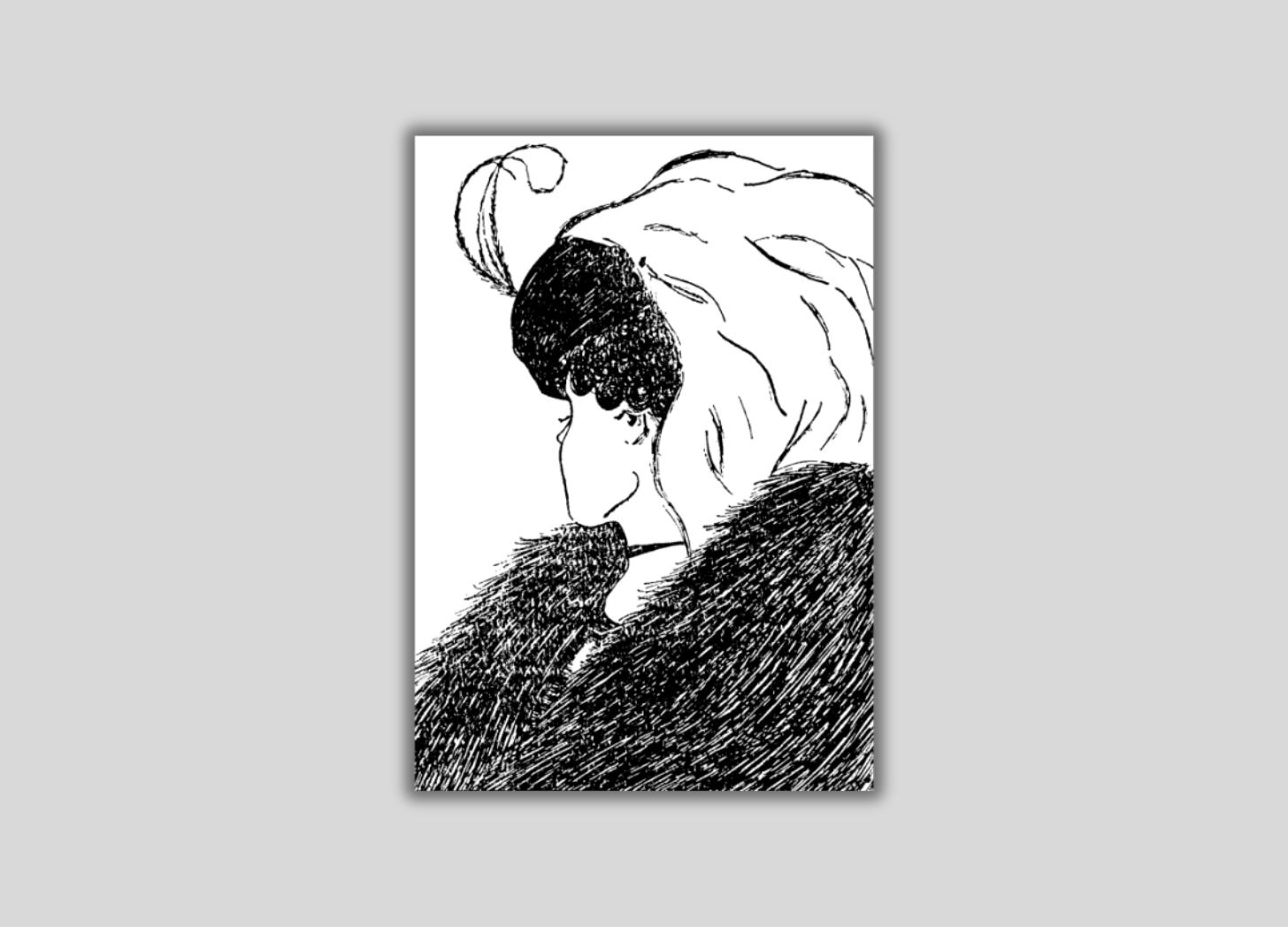

You've seen it. Everyone has. It’s that scratchy, black-and-white sketch where one second you’re looking at a glamorous young lady with her head turned away, and the next, you’re staring at the profile of an elderly woman with a prominent nose and a tucked-in chin. It’s the picture old woman young woman drawing, formally known as "My Wife and My Mother-in-Law."

It is weirdly frustrating.

Once your brain locks onto one image, switching to the other feels like trying to sneeze with your eyes open—it takes a bizarre amount of mental effort. But this isn't just some viral meme from the Victorian era. It is actually a fundamental tool used by psychologists to understand how our brains construct reality out of messy sensory data.

The Real Story Behind the Sketch

Most people think this drawing started on a 1915 postcard. That’s the version by British cartoonist William Ely Hill, which is definitely the most famous one. He published it in Puck, a humor magazine, with a caption that basically dared people to find both women.

But Hill didn't actually invent the concept.

The image actually dates back to an anonymous German postcard from 1888. Even before that, versions of this "ambiguous figure" were floating around folk art circles. It’s a classic example of a "bi-stable" image. That’s just a fancy way of saying your brain can’t see both versions at the exact same time. It’s an either-or situation. Your neurons are basically competing for dominance.

Why You See the Young Girl First (Or Don’t)

Ever wonder why some people spot the elegant jawline of the young woman immediately while others get stuck on the old woman’s large nose?

🔗 Read more: Chuck E. Cheese in Boca Raton: Why This Location Still Wins Over Parents

It’s not random.

A fascinating 2018 study published in the journal Scientific Reports by researchers at Flinders University in Australia suggested that your age might dictate your perception. They showed the picture old woman young woman to 393 participants ranging from ages 18 to 68. The results were pretty wild. Younger people were significantly more likely to see the young woman first. Older participants tended to identify the elderly woman.

This is what psychologists call "own-age bias."

We are biologically wired to recognize faces that look like ours. Our brains are essentially scanners optimized for our own social groups. If you're 22, your brain is looking for 22-year-olds. If you're 70, your neural pathways are primed for the features of your peers. It's a subtle, subconscious filter that changes how you interact with the world.

The Mechanics of the "Flip"

Let’s get technical for a second, but not too much.

When you look at the picture old woman young woman, your primary visual cortex is receiving the same raw data regardless of what you "see." The light hits your retina, goes to the back of your head, and stays the same. The "flip" happens in the higher-order processing areas—the parietal and temporal lobes.

💡 You might also like: The Betta Fish in Vase with Plant Setup: Why Your Fish Is Probably Miserable

The young woman’s ear is the old woman’s eye.

The young woman’s necklace is the old woman’s mouth.

The young woman’s chin is the old woman’s nose.

When your brain decides the line represents a nose, it suppresses the "chin" interpretation. It’s a winner-take-all system. This is why you can’t see both simultaneously. Your brain hates ambiguity. It wants to give you a solid, reliable report of what’s in front of you so you can react to it. If the brain stayed "undecided," you’d be functionally blind to the meaning of the image.

Beyond the Postcard: Why This Matters Today

This isn't just a party trick.

Understanding how we interpret a picture old woman young woman helps AI researchers develop computer vision. Teaching a machine to understand that one set of pixels can have two valid meanings is incredibly difficult. Humans do it naturally, but computers struggle with the nuance of context.

Also, it's a huge lesson in empathy.

If two people can look at the exact same black-and-white drawing and see two completely different human beings, imagine how that applies to politics, relationships, or news. We aren't seeing the world as it is; we're seeing it as we are. Your "truth" is often just a result of which neural pathway fired first.

📖 Related: Why the Siege of Vienna 1683 Still Echoes in European History Today

How to Force the Switch

If you are stuck seeing the old lady and want to find the girl, look at the "nose." Try to re-contextualize it as a jawline. Look at the "eye" and try to see it as an ear.

If you're stuck on the young girl, look at her necklace. That’s the mouth. The "ear" is the eye. Once you see the eye, the rest of the face usually falls into place. It’s about breaking the "top-down" processing your brain is forcing on you.

Moving Toward Better Visual Literacy

If you want to sharpen your brain’s ability to handle ambiguity, don't stop at this one image. There are plenty of others to practice on.

- The Rubin Vase: Do you see two faces or a candlestick? This one focuses on figure-ground perception—what is the object and what is the background?

- The Necker Cube: A simple wireframe cube that seems to flip its orientation the longer you stare at it.

- The Duck-Rabbit: Famously used by philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein to describe "aspect seeing."

Spending time with these images actually builds cognitive flexibility. It teaches you to question your first impression. In a world where we’re constantly bombarded with "obvious" truths, being able to step back and say, "Wait, how else could I look at this?" is a genuine superpower.

The next time you scroll past that picture old woman young woman, don't just blink and move on. Try to hold both images in your mind's eye. Try to feel that weird, itchy sensation in your brain when the image flips. That’s the sound of your neurons working. It’s a reminder that your perspective is just one of many possible realities.

To really master this, try showing the image to someone from a different generation. Don't tell them what it is. Just ask, "What do you see?" Their answer might tell you more about how they view the world than any conversation ever could. It’s a simple test, but it’s one that reveals the hidden architecture of the human mind.

Keep your brain sharp by seeking out these paradoxes. The more you practice seeing what isn't immediately obvious, the better you'll get at navigating the complexities of real life, where the "old woman" and the "young woman" are often standing in the same spot at the same time.