Look at it. Really look at it. If you squint at the original picture from Voyager of Earth, you might actually miss the point entirely. It isn’t a high-definition marvel of modern engineering. It’s grainy. It’s noisy. There’s a weird streak of light cutting across the frame caused by sunlight scattering off the camera’s lens housing. And right there, suspended in one of those beams of light, is a tiny, microscopic-looking speck. That’s us. Everything you’ve ever known—every war, every breakfast, every heartbreak—happened on that one pixel.

Honestly, the "Pale Blue Dot" shouldn't even exist. NASA’s Voyager 1 had finished its primary mission. It had already flown past Jupiter and Saturn. It was screaming toward the edge of the solar system at 40,000 miles per hour. Turning the camera back toward the Sun was risky. There was a real fear that the intense solar radiation would fry the Vidicon tubes—the "eyes" of the spacecraft. But Carl Sagan pushed for it. He knew we needed to see ourselves from the outside.

The day the picture from Voyager of Earth almost didn't happen

It was February 14, 1990. Valentine’s Day. Most people were thinking about chocolate or flowers, but a small team at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) was sending a series of commands to a machine nearly 4 billion miles away. Voyager 1 was roughly 40 times further from the Sun than Earth is. The distance was so vast that it took light—and the radio signals carrying the commands—over five and a half hours to reach the probe.

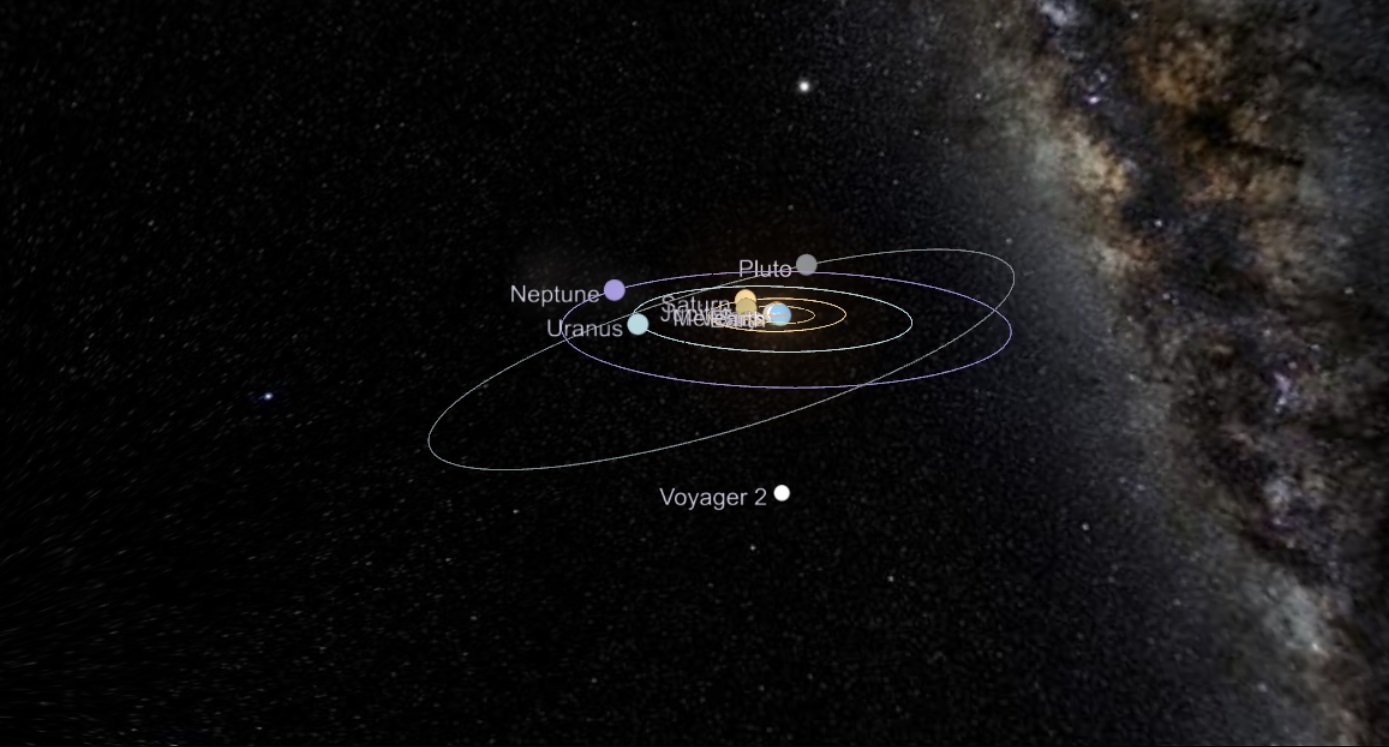

The logistics were a nightmare. Because the spacecraft was moving so fast and was so far away, the Earth appeared incredibly close to the Sun from its perspective. Imagine trying to take a photo of a single grain of sand sitting right next to a massive searchlight. That’s what the imaging team was up against. They took 60 frames in total to create a "Family Portrait" of the solar system, capturing Neptune, Uranus, Saturn, Jupiter, and Venus. Mars was lost in the glare. Mercury was too close to the Sun to see. But the Earth? It was just barely there.

The image wasn't processed immediately. In fact, it stayed on the spacecraft's tape recorder for weeks. We didn't actually see the picture from Voyager of Earth until the data was beamed back and reconstructed on Earth months later. When it finally arrived, it wasn't a glorious blue marble like the "Blue Marble" shot from Apollo 17. It was a lonely, fragile dot.

💡 You might also like: Why It’s So Hard to Ban Female Hate Subs Once and for All

Why the "Pale Blue Dot" is technically a mess

If you're a photography nerd, this image is basically a disaster. The "beams" of light across the photo aren't real celestial phenomena. They are artifacts. Because Voyager was so close to the Sun's position in the sky, light bounced around inside the camera optics. It's a lens flare. By total fluke, the Earth happened to be positioned inside one of those scattered light rays.

- Distance: 3.7 billion miles (6 billion kilometers).

- Exposure time: 0.72 seconds for the Earth frame.

- Resolution: The Earth is less than 0.12 pixels in size.

- Filter: A combination of green, blue, and violet filters was used to create the final color composite.

It’s tiny. It’s less than a pixel. NASA actually had to process the image to make the Earth visible to the human eye, otherwise, it would have been swallowed by the background noise of space.

What most people get wrong about the Voyager mission

People talk about Voyager 1 as if it’s just a floating camera. It’s not. It’s a nuclear-powered time capsule. It’s currently in interstellar space—the space between stars—where the Sun’s solar wind no longer reaches. It left the heliosphere in 2012. Think about that for a second. We have a machine, built in the 1970s with less computing power than a modern car key, that is currently traveling through the void beyond our sun.

A common misconception is that the picture from Voyager of Earth was taken from the edge of the galaxy. Not even close. It was taken from within our own solar system, just past the orbit of Neptune. Even at that relatively "short" distance, our planet looks like a dust mote. If Voyager took a photo from its current location today, Earth wouldn't even be a pixel. It would be invisible.

📖 Related: Finding the 24/7 apple support number: What You Need to Know Before Calling

Sagan’s obsession with this photo wasn't just about science. It was about perspective. He famously noted that "there is perhaps no better demonstration of the folly of human conceits than this distant image of our tiny world." He spent years lobbying NASA leadership to take the shot. Many engineers thought it was a waste of precious power and time. They were wrong. It became the most influential space photograph ever taken, rivaling only "Earthrise" from the moon.

The technical wizardry of 1970s hardware

We’re spoiled now. We have the James Webb Space Telescope sending back infrared masterpieces of deep space. But the Voyager cameras were 1970s television technology. They used Vidicon tubes, which are basically the ancestors of the sensors in your phone. They didn't "click" a shutter and get a digital file. They scanned lines of light intensity, turned them into numbers, and sent those numbers back to Earth via a dish that has to be pointed perfectly at our planet.

The data rate was incredibly slow. To get the picture from Voyager of Earth back to us, Voyager had to transmit at a measly bit rate. It’s like trying to download a movie over a 1990s dial-up connection while standing in the middle of a desert. Actually, it’s much worse than that. The Deep Space Network—a collection of massive radio antennas in California, Spain, and Australia—had to listen incredibly hard to catch the faint whisper of Voyager’s signal across the billions of miles.

Longevity and the slow fade

Voyager 1 and its twin, Voyager 2, are dying. Slowly. Their heaters are being turned off one by one to save power from their decaying plutonium generators. We are losing them. In fact, in late 2023 and early 2024, Voyager 1 started sending back gibberish. The Flight Data System (FDS) had a corrupted memory chip.

👉 See also: The MOAB Explained: What Most People Get Wrong About the Mother of All Bombs

Engineers at JPL had to figure out how to move the code to a different part of the 46-year-old memory without breaking the whole thing. They did it. It was like performing heart surgery on a patient who is four billion miles away using a manual written in 1975. But even with these heroic efforts, the cameras are long gone. They were turned off shortly after the Family Portrait was finished to save power. We will never get another picture from Voyager of Earth. This is it.

The legacy of a single pixel

Why does this matter in 2026? Because we are living in an era of unprecedented planetary transition. When we look at that dot, we see the only home we've ever known. It reminds us that there is no help coming from elsewhere to save us from ourselves.

The image was remastered by NASA in 2020 for its 30th anniversary. Using modern image-processing software, they cleaned up the grain and the "static" while preserving the integrity of the original data. The result is even more haunting. The Earth looks even more solitary. It’s a reminder that for all our technological progress—our AI, our rockets, our satellites—we are still just inhabitants of a very small, very wet rock.

How to use the "Voyager Perspective" in real life

Knowing the history of the picture from Voyager of Earth is one thing, but applying its lesson is another. It’s easy to get bogged down in the "small" stuff—social media arguments, daily stressors, local politics.

- Practice the 10-10-10 rule with a cosmic twist. Will this problem matter in 10 minutes? 10 months? Or when viewed from 4 billion miles away? Usually, the answer is no.

- Support the Deep Space Network. These antennas are the only reason we can still talk to our furthest explorers. Advocacy for NASA funding ensures we don't go "deaf" to the signals coming from the edge of the dark.

- Download the high-res remaster. Put it on your desktop or print it out. Seeing that tiny blue speck daily is a grounded way to maintain a sense of humility and environmental stewardship.

- Read "Pale Blue Dot" by Carl Sagan. Don't just look at the photo. Read the prose that accompanied it. It is arguably some of the most important philosophy written in the 20th century.

The Voyager mission wasn't just about taking pictures. It was about finding our place in the hierarchy of the universe. It turns out, we aren't at the center. We aren't even a major player on the cosmic stage. We're just a tiny, fragile, beautiful accident. And that's okay. In fact, it makes our existence even more precious.

If you want to track where Voyager is right now, NASA’s "Eyes on the Solar System" app gives you a real-time view of its distance and velocity. It’s currently over 15 billion miles away from us, still moving, still traveling into the great unknown, carrying the memory of that one tiny blue pixel with it.