You’ve probably seen it. A vibrant, oval-shaped smear of speckles that looks like a tie-dye egg or a heat map of a very dusty room. People call it a photo of entire universe, but honestly, that’s a bit of a stretch. It isn't a photograph in the way your iPhone takes a picture of your cat. It’s more of a forensic reconstruction of what the cosmos looked like when it was a "toddler"—barely 380,000 years old.

We call it the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB).

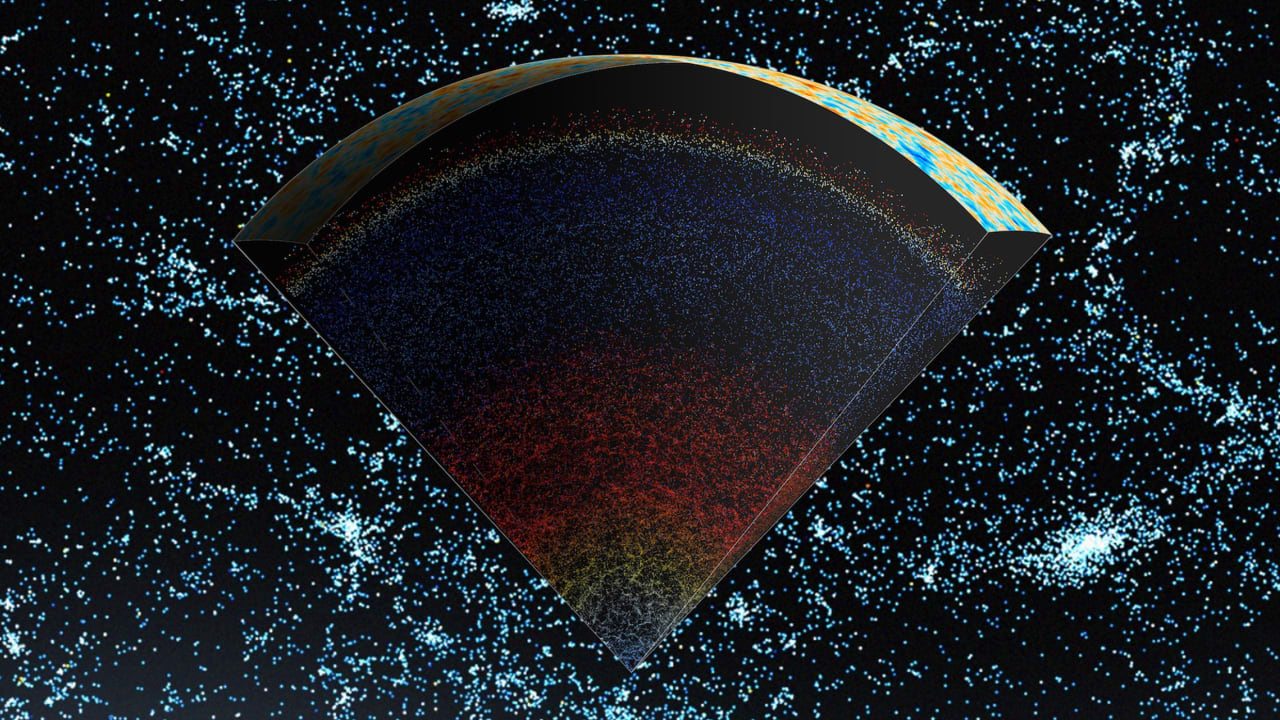

The universe is huge. Like, mind-bendingly, "I-can't-sleep-at-night" huge. Capturing a single image of it is technically impossible because light has a speed limit. When we look out, we are looking back. If you want a photo of the "entire" universe as it exists right now, you're out of luck. Physics says no. But scientists have managed to capture the "afterglow" of the Big Bang, and that is what most people are actually looking at when they search for that iconic image.

The image that shouldn't exist

In 1964, two guys named Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson were messing around with a giant horn antenna in New Jersey. They weren't looking for the beginning of time. They were just trying to clear out some annoying background noise that sounded like static. They even scrubbed "white dielectric material"—basically pigeon poop—off the antenna, thinking that was the culprit.

It wasn't.

That hiss was the first "view" of the CMB. They had accidentally stumbled upon the oldest light in existence. Fast forward a few decades, and missions like COBE, WMAP, and finally the European Space Agency’s Planck satellite gave us the high-definition version we see today. It’s a snapshot of the universe when it was a hot, dense soup of plasma. Before stars. Before galaxies. Before anything had a chance to get organized.

Why the colors aren't "real"

If you could fly back 13.8 billion years, you wouldn't see those blue and red splotches. Those colors represent temperature fluctuations. The blue parts are slightly cooler, and the red parts are slightly warmer. We are talking about differences of about one-hundred-thousandth of a degree. Tiny.

But these tiny ripples are everything.

👉 See also: How to Log Off Gmail: The Simple Fixes for Your Privacy Panic

Without these slight irregularities, gravity wouldn't have had "clumpy" spots to pull matter together. No clumps means no stars. No stars means no planets. No planets means no you. Basically, that grainy photo of entire universe is a blueprint of the skeleton of our reality. It shows the seeds of the massive galaxy clusters we see today through the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST).

Speaking of Webb, it's important to differentiate. People often confuse Webb’s Deep Field images—those sparkly, jewel-toned photos of distant galaxies—with the "entire universe." They aren't the same. Webb looks at the "teenager" years of the universe. The CMB (the oval map) is the "ultrasound."

The problem with "Entire"

When we talk about a photo of the "entire" universe, we have to talk about the Observable Universe.

Because the universe is expanding—and doing so at an accelerating rate—there are parts of space that are moving away from us faster than the speed of light. Their light will literally never reach us. We are trapped in a bubble of visibility about 93 billion light-years across. Anything outside that? We can't see it. We can't photograph it. It might as well not exist for us.

So, when you see a 2D map of the sky, you’re seeing the inside of that bubble projected onto a flat surface, much like a map of the Earth tries to flatten a globe.

Dark Matter and the stuff we can't see

Most of that "photo" is actually a lie of omission.

Everything you see in a standard photograph—stars, gas, dust, your neighbor's house—only makes up about 5% of the universe. The rest is Dark Matter and Dark Energy. We can't photograph them because they don't interact with light. We only know they’re there because they pull on the stuff we can see.

✨ Don't miss: Calculating Age From DOB: Why Your Math Is Probably Wrong

Think of it like looking at a photo of a forest at night. You can see the leaves because of your camera flash, but you can't see the wind moving them. You just see the effect. That’s what our current "whole universe" maps are like. They show the glowing "leaves" but miss the invisible "wind" that’s actually running the show.

What's actually happening in that graininess?

Let's get into the weeds for a second. The reason the CMB is so vital is because of something called Baryon Acoustic Oscillations.

Imagine the early universe was a giant bell. The Big Bang was the "clapper" hitting the bell. This sent sound waves—actual pressure waves—rippling through the hot plasma. When the universe finally cooled down enough for light to travel freely (the moment the "photo" was taken), those ripples were frozen in place.

By studying the size and spacing of the splotches in the photo of entire universe, physicists can calculate:

- How old the universe is (13.787 billion years, give or take).

- How fast it’s expanding (the Hubble Constant, though there's a big fight about this number right now).

- What it’s made of.

It’s like looking at a cake and being able to tell exactly how much flour, eggs, and sugar were used just by looking at the bubbles in the sponge.

The JWST factor

Lately, the James Webb Space Telescope has been throwing a wrench in things. It’s seeing galaxies that are way too big and way too old for what we thought was possible based on our CMB maps.

Some researchers, like those working on the CEERS Survey, have found galaxies that existed just 300 million years after the Big Bang. They are bright. They are massive. And according to some models, they shouldn't have had enough time to grow that big. This is why science is cool—it’s never "settled." We have the photo, but we’re still arguing about what’s in the background.

🔗 Read more: Installing a Push Button Start Kit: What You Need to Know Before Tearing Your Dash Apart

How to actually "see" it yourself

You don't need a billion-dollar satellite to "see" a photo of entire universe.

If you have an old-school analog TV—the kind with the tubes and the "snow" on channels that don't exist—about 1% of that static is actually the Cosmic Microwave Background. You are literally watching the radiation from the Big Bang hit your antenna. It's the most "lo-fi" version of the universe's first selfie.

Common misconceptions to ignore

People love to say the universe is "flat." When you see the oval photo, it looks like a pancake, right?

But "flat" in cosmology doesn't mean it looks like a piece of paper. It means that if you and a friend started flying in two parallel lines across the universe, you’d stay parallel forever. You wouldn't eventually cross paths like you would on a sphere. The photo of entire universe helps prove this "flatness" because of the way the light is distributed. If the splotches were distorted, we'd know the universe had a curve.

Also, the "center." There is no center in that photo. Every point in that image was, at one time, the same point. The Big Bang didn't happen in space; it was the creation of space. So when you look at that map, you’re looking at "here" and "there" simultaneously.

Practical steps for the space enthusiast

If you want to dive deeper than just looking at a pretty desktop wallpaper, there are a few things you can actually do to understand what you're looking at.

- Check out the NASA LAMBDA site. It’s where the raw data lives. It isn't pretty, but it’s the actual numbers that created the famous maps.

- Use the Chromoscope tool. It’s an interactive website that lets you toggle between different wavelengths. You can see the "photo" in X-ray, Infrared, and Microwave. It’s the best way to realize that what we see with our eyes is just a tiny sliver of reality.

- Look for "The Hubble Ultra-Deep Field." While not the "entire" universe, it’s the most "human" version of it. It’s a tiny patch of sky—about the size of a grain of sand held at arm's length—that contains thousands of galaxies.

- Download "SkyView." It’s a "Virtual Observatory" that lets you generate your own maps of the sky based on different surveys. You can literally generate your own version of a universal photo from your laptop.

Understanding the photo of entire universe is less about seeing a picture and more about reading a history book written in light. We are currently living in a golden age of cosmology. Between the Planck data we already have and the new data Webb is sending back every day, our "map" is getting clearer, even if it’s getting more confusing at the same time.

The next step is to look up. If you're interested in how these images are processed, research "false color imaging in astronomy" to see how scientists turn invisible microwave data into the colorful maps we see in news headlines. Or, explore the "Hubble Tension" to understand why our best photos of the early universe don't quite match our photos of the current one.