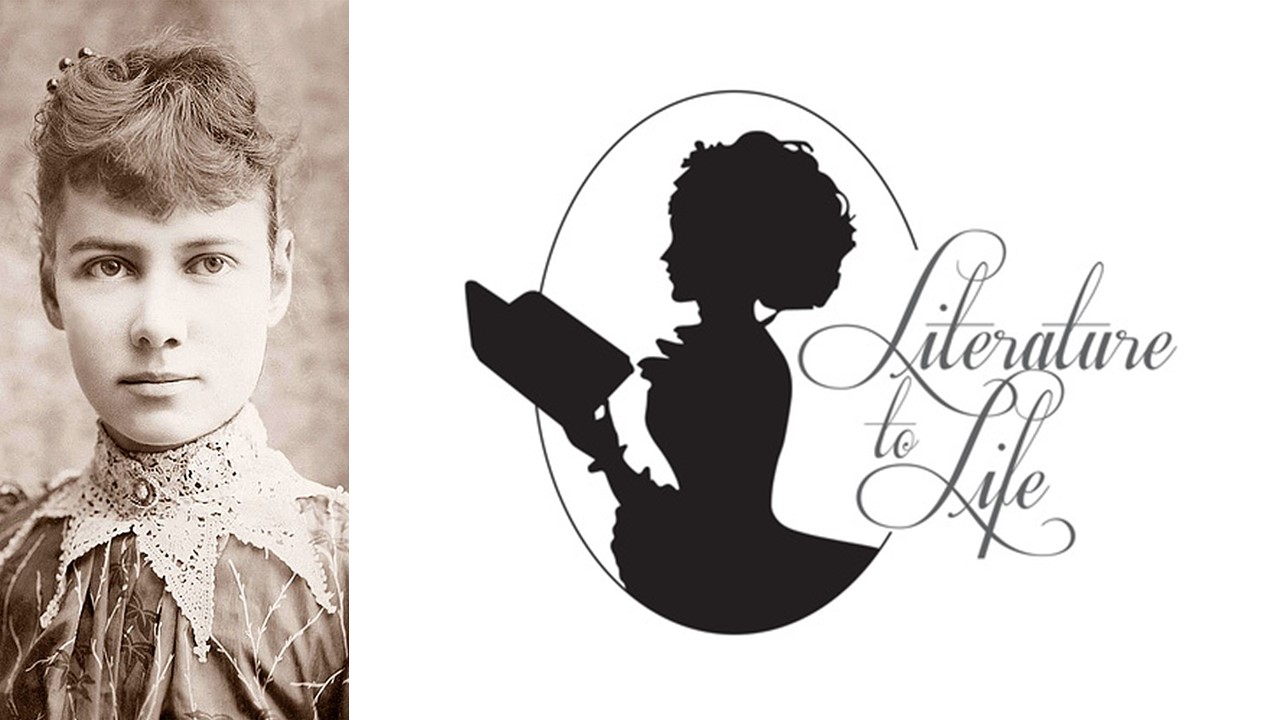

Honestly, it’s hard to imagine a journalist today doing what Elizabeth Cochrane Seaman did in 1887. You probably know her as Nellie Bly. She didn't just write a "think piece" or aggregate some tweets; she checked herself into a literal nightmare. To understand the impact of Ten Days in a Mad-House Nellie Bly, you have to realize that investigative journalism was basically in its infancy. There were no hidden cameras or digital recorders. There was just a 23-year-old woman feigning insanity to get committed to the Blackwell’s Island Insane Asylum.

She did it for a job. Specifically, she did it for Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World.

The premise was simple but terrifying. Could a sane person be committed to an asylum? And if they were, what happened once the heavy doors locked behind them? What Bly found wasn't just "poor care." It was a systematic stripping away of human dignity that feels like something out of a horror movie, except it was real life for hundreds of women in New York City.

The Performance of "Insanity"

Bly practiced her "crazy face" in front of a mirror. It sounds almost silly until you realize the stakes. She checked into a temporary boarding house for women under the name Nellie Brown, acting out a state of amnesia and paranoia. She stayed up all night. She stared blankly at walls. She told people she was looking for her lost trunks.

It worked.

Actually, it worked too well. Within a few days, she was hauled before judges and medical "experts" who spent about five minutes looking at her before declaring her "positively demented." One of the most chilling parts of Ten Days in a Mad-House Nellie Bly is how easily the professionals were fooled. They saw what they expected to see: a "hysterical" woman. Once that label was applied, everything she did—even acting perfectly normal later—was viewed through the lens of madness.

The Reality of Blackwell’s Island

Blackwell’s Island, now known as Roosevelt Island, was a dumping ground. It housed a prison, a charity hospital, and the asylum. When Bly arrived, the "treatment" began. It wasn't medicine. It was cold. It was hunger. It was physical abuse.

👉 See also: Why the Man Black Hair Blue Eyes Combo is So Rare (and the Genetics Behind It)

The food was a joke. We’re talking about spoiled beef, "pinkish" water that was supposed to be tea, and bread that was essentially dried dough. Bly described the butter as "rancid" and the overall dining experience as an invitation to starvation. But the physical environment was worse. The buildings were freezing. The nurses—many of whom were essentially uneducated guards with zero medical training—forced the inmates to sit on straight-backed wooden benches from 6:00 a.m. until 8:00 p.m.

No talking. No moving. No reading.

Think about that for a second. If you weren't mentally ill when you went in, sitting in total silence on a hard bench for 14 hours a day in a drafty room would probably get you there pretty fast. Bly noted that this "treatment" was designed to break the spirit.

The "Bath" Terror

One specific detail from the book that always sticks with people is the bathing ritual. In the late 19th century, hygiene in public institutions was more about humiliation than health. Bly was stripped naked in a room full of other women and doused with buckets of ice-cold water.

It wasn't a wash. It was an assault.

She was then scrubbed with a rough brush until her skin was raw and dried with a towel that had already been used by dozens of other patients, some of whom had contagious skin diseases. This wasn't an accident or a lack of resources; it was a deliberate method of control. The nurses used the threat of the cold bath to keep the women in a state of constant, low-level terror.

✨ Don't miss: Chuck E. Cheese in Boca Raton: Why This Location Still Wins Over Parents

Why Nobody Listened to the "Crazy" Women

The most heartbreaking part of Bly’s account involves the other women. She met many who were clearly sane. Some were just immigrants who couldn't speak English and had been picked up off the street because they looked "confused." One woman was committed because she had a falling out with her husband and he wanted her out of the way.

Because they were in an asylum, their protests were ignored. "I am sane!" is exactly what a "crazy" person would say, right? That’s the catch-22 Bly exposed.

The nurses were notoriously cruel. Bly witnessed them choking patients, beating them, and pulling their hair. When the doctors made their rounds—usually very brief and superficial—the patients were too scared to complain. And if they did? The doctors just smiled and made a note about their "delusions of persecution."

The Aftermath and the Grand Jury

Pulitzer didn't leave her in there forever. After ten days, a lawyer from the New York World came to secure her release. Bly walked out, wrote her series of articles, and the city went into a frenzy. It was a sensation.

People were outraged. Not just because of the cruelty, but because it was so easy for a sane, "respectable" woman to be trapped. A Grand Jury was empaneled. Bly accompanied them on a tour of the facility.

The asylum tried to clean up. They fired the worst nurses. They improved the food. They even tried to hide the sanest patients before the jury arrived. But Bly knew where the bodies were buried, metaphorically speaking. Her testimony and the sheer public pressure led to an increase of $1,000,000 in the budget for the Department of Public Charities and Corrections.

🔗 Read more: The Betta Fish in Vase with Plant Setup: Why Your Fish Is Probably Miserable

That was a massive amount of money in the 1880s.

The Legacy of Ten Days in a Mad-House Nellie Bly

We like to think we’ve evolved past the horrors of Blackwell’s Island. In many ways, we have. We don't use ice-water baths as punishment (usually). We have laws like the Lanterman-Petris-Short Act in California that make it much harder to commit someone against their will.

But the core issues Bly raised—the "othering" of the mentally ill, the lack of funding, and the tendency to ignore the voices of the vulnerable—haven't gone away.

Bly pioneered "stunt" journalism, but it was stunt journalism with a soul. She proved that the press could be a hammer for social change. She didn't just report on the news; she forced the news to happen.

Actionable Takeaways for the Modern Reader

If you're looking to dive deeper into this history or support better mental health advocacy today, consider these steps:

- Read the Source Material: Don't just watch a documentary. The original text of Ten Days in a Mad-House Nellie Bly is in the public domain. It’s a fast, visceral read that feels surprisingly modern in its pacing.

- Support Investigative Non-Profits: Organizations like ProPublica or the Marshall Project continue Bly’s legacy by looking into institutional abuses in prisons and hospitals.

- Understand Patient Rights: Familiarize yourself with the "Informed Consent" laws in your state. Knowing the legal threshold for involuntary commitment is vital for anyone advocating for a loved one.

- Visit the Memorial: If you’re ever in New York, go to Roosevelt Island. There is a massive art installation called "The Girl Puzzle" by Amanda Matthews. It honors Bly and the women she tried to save, specifically focusing on the faces of those who were marginalized.

Nellie Bly didn't just change the law; she changed how we look at the people we’d rather forget. She showed that the difference between "sane" and "insane" is often just a matter of who has the power to tell the story.