John Wayne was already a star by 1944. Stagecoach had happened five years prior, and he was firmly entrenched as the face of the American West. But there is something about Tall in the Saddle that feels different from his usual cavalry or lone-drifter roles. It’s grittier. It’s got a weird, almost noir-like mystery at its center. And honestly? It features one of the most unapologetic, "don't-mess-with-me" versions of the Duke ever put on celluloid.

The film follows Rocklin, a ranch hand who arrives in a dusty town only to find out his new employer has been murdered. Standard setup, right? Well, not exactly.

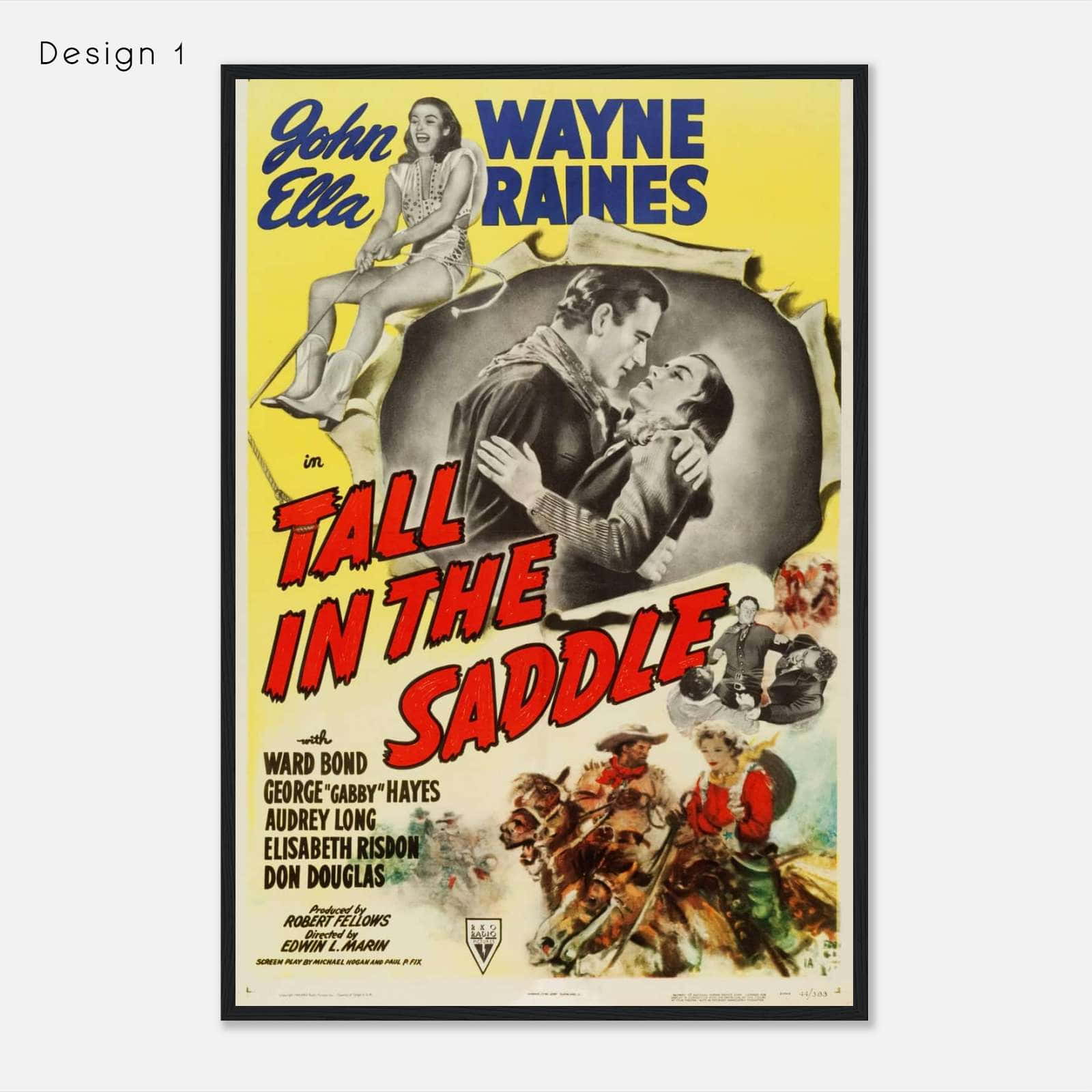

The Gritty Mystery of Tall in the Saddle

Most Westerns of the mid-40s were pretty black and white when it came to morality. You had the guy in the white hat and the guy in the black hat. Tall in the Saddle messes with that a bit. Rocklin isn't particularly nice. He’s a bit of a misogynist—specifically saying he doesn't want to work for women—and he’s got a chip on his shoulder the size of the Sierra Nevada.

Directed by Edwin L. Marin, the movie leans into the whodunit aspect. You’ve got a town full of people who might have killed the ranch owner, and Rocklin is stuck in the middle of a legal battle over an inheritance. It’s basically a detective story where everyone wears spurs.

💡 You might also like: Why Come On Up to the House Tom Waits Still Hits Harder Than Anything Else on the Radio

Ella Raines and the Breakout Performance

While Wayne is the draw, Ella Raines as Arly Harolday is the real firecracker here. She isn't your typical 1940s damsel. In one of the most famous scenes, she literally tries to run Wayne down with a buckboard and later whips a gun out faster than most of the men in the film. She’s volatile. She’s rich. She’s angry.

The chemistry between Wayne and Raines is palpable because it's built on mutual annoyance. It’s not a soft romance. It’s a "we might kill each other or get married" kind of vibe. Raines was a favorite of producer John Houseman and director Robert Siodmak, usually appearing in noir films like Phantom Lady. Bringing that "femme fatale who might actually be a good person" energy into a Western was a stroke of genius.

Why 1944 Was a Weird Year for Westerns

Context matters. In 1944, the world was at war. Hollywood was churning out combat films and patriotic musicals. The Western had become a bit of a comfort food genre, but it was also starting to evolve.

You see, Tall in the Saddle wasn't a massive prestige picture like a John Ford epic. It was an RKO Radio Pictures production. It had a budget, but it wasn't infinite. Despite that, it looks fantastic. The cinematography by Harry J. Wild uses shadows in a way that feels more like a crime thriller than a sprawling landscape film. It’s tight. It’s claustrophobic in the town scenes.

The supporting cast is a "who's who" of character actors.

- George "Gabby" Hayes: The quintessential sidekick. He provides the comic relief, but he's actually useful to the plot for once.

- Ward Bond: A Wayne staple. He plays Judge Arny, and his presence always adds a layer of "big man" tension to the screen.

- Elisabeth Risdon: Playing the "spinster aunt" archetype but with enough venom to keep you guessing about her motives.

Fact-Checking the Production

There’s a lot of nonsense floating around about this movie. Let’s clear some of it up.

👉 See also: Why Abhi Na Jao Chodkar Lyrics Still Define Romance After 60 Years

People often think John Wayne directed parts of this because his influence was so heavy. He didn't. Edwin L. Marin was a journeyman director who knew how to keep a pace. However, Wayne was heavily involved in the script adjustments. He knew the Rocklin character needed to be tougher and less talkative than the original Saturday Evening Post serial by Gordon Ray Young.

The film was a massive hit for RKO. It pulled in a profit of over $700,000 at the time—which was huge back then. It solidified the idea that Wayne didn't need a massive ensemble to carry a movie; he just needed a horse and a mystery.

Key Takeaways for Film Buffs

If you're watching this for the first time, or the fiftieth, keep an eye on the dialogue. It’s surprisingly sharp.

- The "No Women" Rule: Rocklin's initial refusal to work for women isn't just a 40s trope; it sets up the entire power dynamic with Arly. Watching her break down that wall is the movie's real heart.

- The Fight Scenes: There is a brawl in a saloon between Wayne and a character played by Cy Kendall. It’s choreographed with a brutality that feels ahead of its time. No "stage punches" here—they look like they’re actually trying to break furniture.

- The Ending: No spoilers, but the resolution of the murder mystery is actually clever. It’s not just a random guy in a mask. The clues are there if you look for them.

Watching Tall in the Saddle Today

Is it dated? Sure. Some of the social attitudes are firmly rooted in the 1940s. But as a piece of genre filmmaking, it’s top-tier. It represents a bridge between the simple Westerns of the 30s and the psychological "Adult Westerns" that would come in the 1950s like The Searchers or The Naked Spur.

If you want to understand the evolution of the "Cowboy Hero," you have to watch this. Rocklin isn't a hero because he’s nice. He’s a hero because he’s the only one in town who isn't a liar. That’s a theme that never really goes out of style.

How to Appreciate the Craft

To truly get the most out of Tall in the Saddle, pay attention to the pacing. It’s only about 87 minutes long. In that time, it establishes a murder, a romantic triangle, a land dispute, and a secret identity. Modern movies could learn a thing or two about that kind of efficiency.

- Check the lighting: Look at how the night scenes are filmed. The use of high-contrast lighting is pure noir.

- Listen to the score: Roy Webb’s music doesn't just do the "yee-haw" thing; it builds genuine suspense during the trail scenes.

- Observe the costuming: Wayne’s look here—the vest, the specific hat tilt—became the "John Wayne Look" for the next decade.

Go find a high-definition restoration. The black and white photography is crisp, and seeing the dust kick up during the stagecoach sequences in 4K or even a good Blu-ray transfer makes you realize why people went to the cinema twice a week back then. It was an escape. And 1944 was a year when everyone needed an escape.

📖 Related: Why the Paley Center for Media Is the Only Place That Actually Remembers TV History

Next Steps for the Classic Film Fan

Start by comparing this to Stagecoach. You’ll see how much Wayne’s screen presence matured in just five years. Then, look up Ella Raines' other work from the same era; she was a powerhouse who often gets overshadowed by bigger names like Bacall or Stanwyck. Finally, track down the original Gordon Ray Young story to see how the screenwriters tightened the narrative for the film.