Bob Dylan was barely twenty-one when he walked into Columbia’s Studio A in late 1962. He was skinny, nervous, and carrying a guitar that looked too big for him. He started playing this rambling, nervous blues riff. It wasn't a polished pop song. It was a fever dream. That song, Talkin' World War 3 Blues, eventually landed as the penultimate track on The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan in 1963. It remains one of the weirdest, funniest, and most terrifying looks at the end of the world ever recorded.

Honestly, we don't talk enough about how funny it is. People treat Dylan like this marble statue of a "serious folk singer," but this track is basically a stand-up comedy routine about nuclear annihilation. It captures a specific brand of American paranoia that feels eerily familiar today.

The Cold War Anxiety Nobody Wanted to Admit

The early sixties were a mess. You had the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962, which happened right around the time Dylan was writing and refining this material. Everyone was half-convinced they’d wake up as a pile of ash.

Dylan didn't write a "we shall overcome" anthem here. He wrote about a guy going to a psychiatrist because he’s having dreams about the fallout. The narrator describes a dream where he’s the only person left in the city. He tries to start a car, he tries to find a payphone, and he even tries to talk to a girl who thinks he’s a Communist just because he’s alive. It’s absurd. It’s dark.

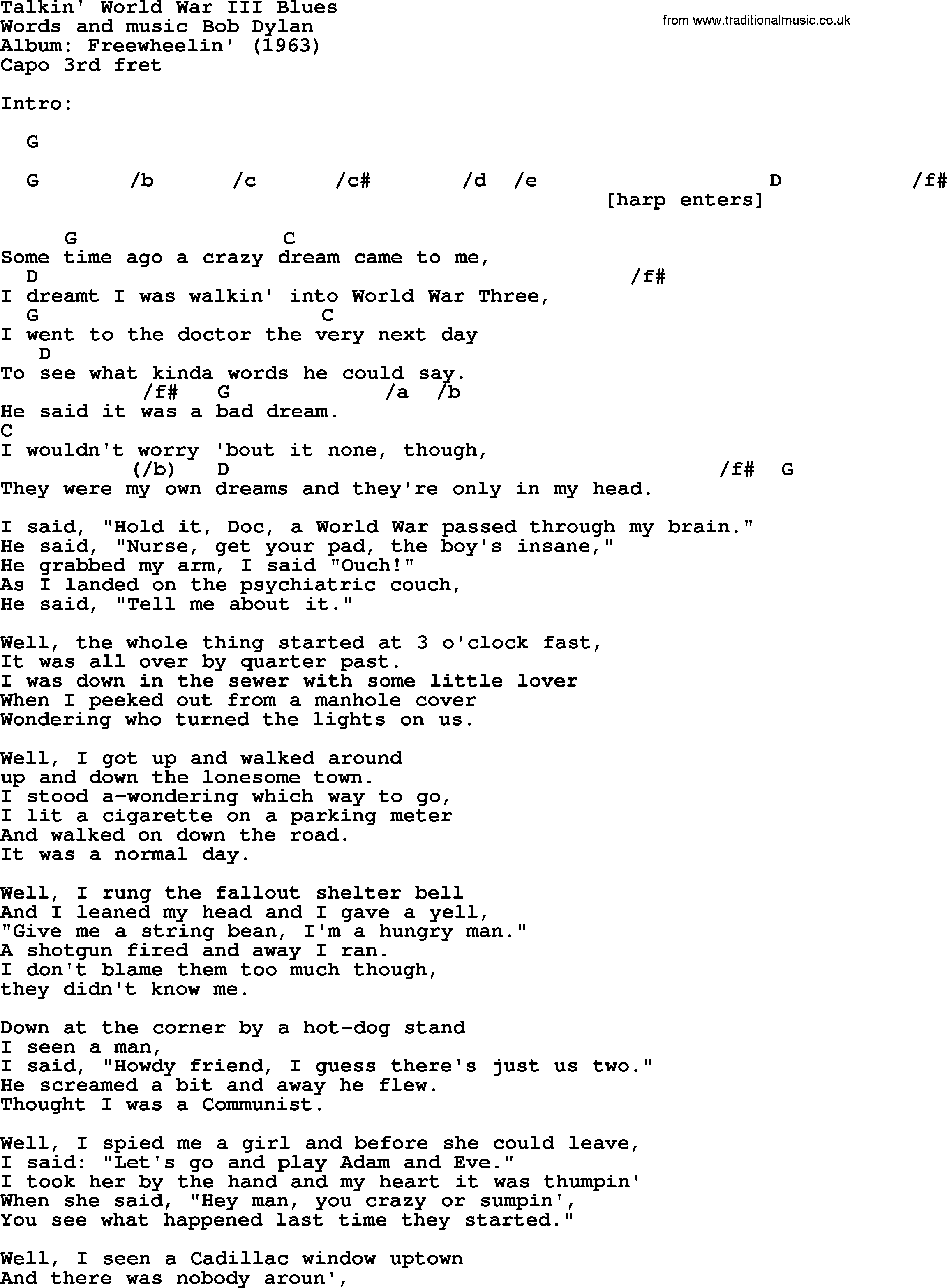

Most protest music from that era felt heavy and moralistic. Dylan went the other way. He used the "talkin' blues" format—a rhythmic, speech-like style popularized by Woody Guthrie—to make the apocalypse feel like a bad joke. By making us laugh at the "button-pushers," he stripped them of their power. It was a genius move.

Why the Humor in Talkin' World War 3 Blues Matters

When you listen to the lyrics, the punchlines come fast. He talks about seeing a man on the street and shouting "Hey, hey, help me get this thing lonesome!" only for the man to run away in fear. Then there’s the bit about the hot dog stand. He’s hungry in the middle of the wasteland, and even in the dream, he’s thinking about a snack.

📖 Related: Isaiah Washington Movies and Shows: Why the Star Still Matters

It’s human.

That’s what’s missing from a lot of modern political music. Today, everything is a lecture. In Talkin' World War 3 Blues, Dylan isn't lecturing you on the dangers of nuclear proliferation. He’s showing you how lonely and stupid the end of the world would actually be.

The production on the track is bare-bones. You can hear Dylan’s feet tapping on the wooden floor of the studio. You can hear him chuckle at his own jokes. This wasn't a calculated "hit." It was a snapshot of a kid trying to process the fact that his leaders might blow up the planet before he could grow up. It’s raw.

Breaking Down the "Dream" Structure

The song is framed as a session with a doctor. The narrator explains his dream, and then the doctor tells him he had the same dream. Then the nurse says she had it too. This is the core of the song’s brilliance. It suggests a collective psychosis. We are all dreaming of the end because we are all living under the shadow of it.

- The Loner Element: The narrator is wandering through a deserted city.

- The Paranoia: Characters in the dream accuse each other of being "Reds" even when there's no government left to care.

- The Irony: He finds a fallout shelter but can't get in, or finds people who are more afraid of him than the radiation.

It’s a cycle of isolation. Dylan nails the feeling that even in a shared catastrophe, humans will find a way to stay divided. He ends the song with that famous line about "I’ll let you be in my dreams if I can be in yours." It’s sort of a peace offering, but a cynical one. He’s saying that since we’re all losing our minds together, we might as well get comfortable.

👉 See also: Temuera Morrison as Boba Fett: Why Fans Are Still Divided Over the Daimyo of Tatooine

The Connection to Woody Guthrie and Folk Tradition

You can't talk about this song without mentioning Woody Guthrie. Dylan was obsessed with him. Guthrie’s "Talkin' Dust Bowl Blues" used the same deadpan delivery to talk about the ecological and economic disaster of the 1930s.

Dylan took that old-school Americana framework and plugged it into the Atomic Age. It was a bridge between the struggles of the Great Depression and the existential dread of the 1960s. He proved that the "blues" weren't just about losing your lover or your job; they could be about losing your entire species.

Critics at the time, like those at Sing Out! magazine, were sometimes divided on Dylan’s shift toward more surrealist imagery. They wanted more songs like "Blowin' in the Wind"—clear, metaphorical, and easy to sing in a group. But Talkin' World War 3 Blues is a solo experience. It’s meant to be heard in a dark room where you’re wondering if that siren outside is a test or the real thing.

Why This Track Ranks Above Other "Apocalypse" Songs

Think about "99 Luftballons" or "It's the End of the World as We Know It (And I Feel Fine)." Those are great pop songs. But they are polished. They have hooks. Dylan’s track is messy. It’s basically a monologue with a soundtrack.

Because it’s so conversational, it feels more honest. It doesn't age because the fear of "some guy pushing a button" hasn't gone away; it just changed names. Whether it’s 1963 or 2026, the idea that our lives are at the mercy of a few people in a room we’ll never enter is a terrifying constant.

✨ Don't miss: Why Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy Actors Still Define the Modern Spy Thriller

People often get the ending wrong. They think it's a hopeful call for unity. It’s really not. It’s a plea for empathy in a world that has gone completely insane. Dylan isn't saying "let's all get along." He's saying "let's at least acknowledge we're all seeing the same nightmare."

What You Can Learn from Dylan’s Songwriting Today

If you’re a creator, or just someone interested in how culture shifts, there’s a massive lesson in this track. Humor is often a better weapon than anger. If Dylan had yelled about the military-industrial complex for five minutes, the song would be a period piece. Because he made it a comedy about a guy trying to buy a hot dog in a nuclear winter, it’s a masterpiece.

Complexity wins. Don't be afraid of being "weird" or "rambling." The imperfections in the recording—the way his voice cracks, the slightly out-of-tune guitar—are exactly why people still listen to it sixty years later. It feels like a human being talking to you.

Actionable Takeaways for Music History Buffs

To really understand the impact of Talkin' World War 3 Blues, you have to look past the lyrics and into the context of 1963. Here is how to dive deeper into this specific era of Dylan's work:

- Listen to the "Talkin' Blues" lineage: Track down Woody Guthrie’s original "Talkin' Dust Bowl Blues" and Pete Seeger’s "Talking Atom." You’ll see exactly where Dylan stole the "vibe" and how he improved it.

- Compare the studio version to the live ones: Dylan often changed the lyrics to his "talkin'" songs on the fly. Check out the 1963 Carnegie Hall performance. The timing is different, and the jokes land with more bite because he has a live audience laughing.

- Research the 1962/1963 News Cycle: Look at the headlines from the New York Times during the weeks Dylan was in the studio. The fear wasn't hypothetical; it was the front page.

- Analyze the "Dream" Trope: Notice how Dylan uses dreams in other songs like "Bob Dylan's 115th Dream." He uses the subconscious as a way to criticize society without being sued or censored.

The song is a reminder that art doesn't have to be pretty to be important. Sometimes, it just needs to be honest enough to admit that we’re all a little bit terrified of what’s coming next. Dylan didn't have the answers, and he didn't pretend to. He just gave us a way to laugh while we waited for the sirens.