It’s May 1967. The world is about to shift. In a small studio in New York, three men—Eric Clapton, Ginger Baker, and Jack Bruce—are messing around with a sound that feels like it’s vibrating from another dimension. They’re recording Tales of Brave Ulysses by Cream, and honestly, rock music was never the same after they hit the record button. It wasn't just a song. It was a collision of Greek mythology, a brand-new guitar pedal, and a level of musicianship that most bands today still can't touch.

If you’ve ever sat in a dark room with headphones on and felt that weird, underwater "wah-wah" sound wash over you, you’ve experienced the ghost of this track. It’s heavy. It’s trippy. And it’s surprisingly short, clocking in at just under three minutes. But in those 166 seconds, Cream managed to pack in more innovation than most bands do in a whole career.

The Secret Weapon: That First Wah-Wah Pedal

You can't talk about Tales of Brave Ulysses by Cream without talking about the wah-wah pedal. It’s the heartbeat of the track. Legend has it that Eric Clapton had just discovered the Vox Clyde McCoy wah-wah pedal. He was obsessed. Before this song, nobody really knew what to do with that piece of gear. It was basically a novelty item.

Clapton changed that.

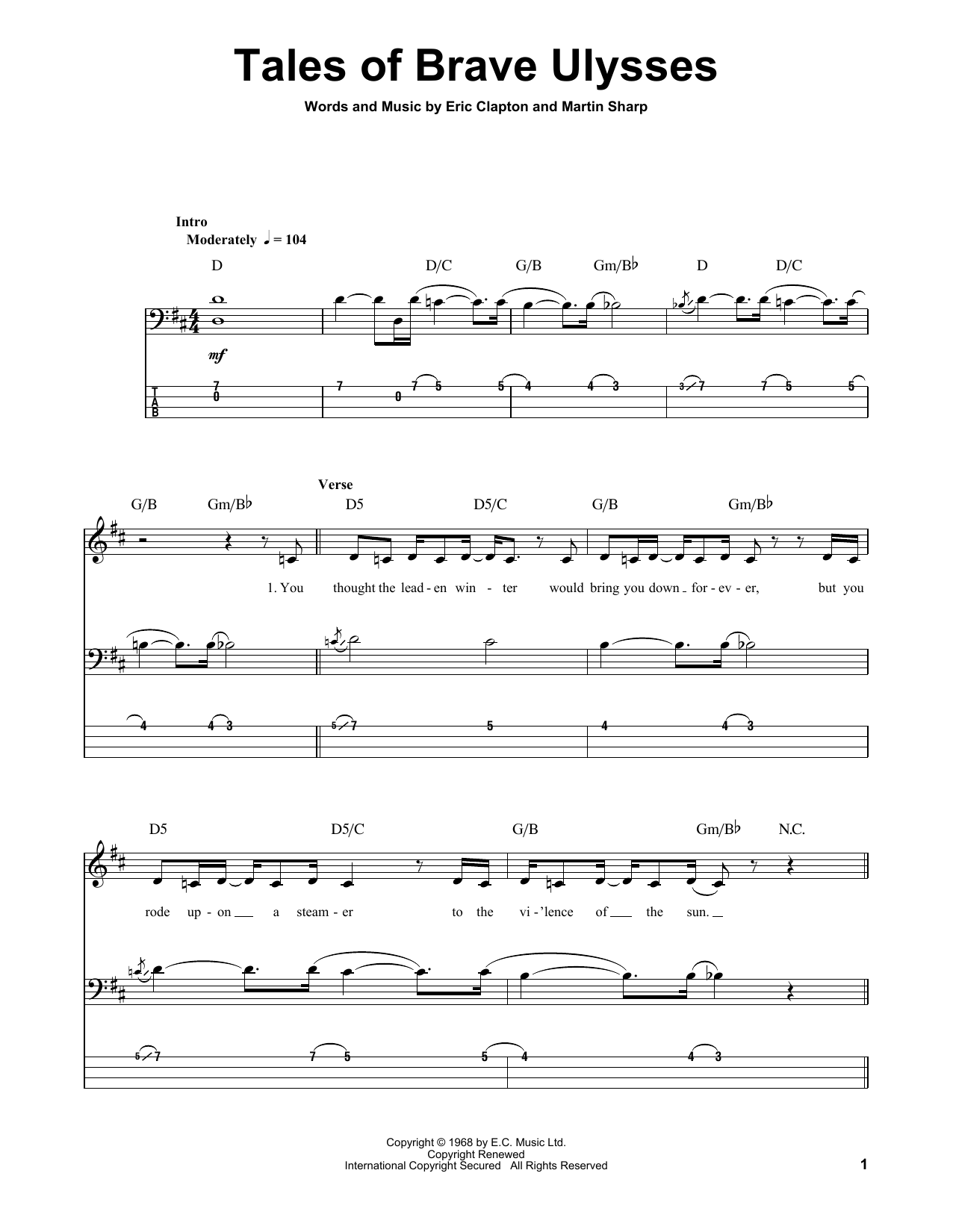

The song opens with that iconic, descending D-minor chord progression. But instead of just strumming it, Clapton uses the pedal to make the guitar "talk." It mimics the sound of the sirens from the Odyssey, crying out across a metaphorical ocean. It’s haunting. While Jimi Hendrix usually gets the credit for mastering the wah-wah (think "Voodoo Child"), it was actually Clapton on this specific track who put the effect on the map for the masses. It was the first time most listeners had ever heard that "crying" guitar sound.

💡 You might also like: Not the Nine O'Clock News: Why the Satirical Giant Still Matters

Martin Sharp and the Poetry of the Sea

The lyrics aren't your typical "I love you, baby" rock fare. They’re dense. They’re strange. Martin Sharp, an Australian artist who lived in the same building as Clapton (the famous Pheasantry in Chelsea), actually wrote them. He wasn't even a songwriter, really. He was a painter and a cartoonist.

Sharp had been traveling and wrote a poem on a piece of paper. He showed it to Clapton, who loved the imagery of "tales of brave Ulysses" and the "tiny purple fishes." It’s basically a psychedelic retelling of Homer’s Odyssey. You have references to the sirens, the "shores of everywhere," and the "silver horses." It sounds like a fever dream because it kind of was. Sharp’s lyrics gave the song a high-art feel that separated Cream from the more straightforward blues acts of the time.

Jack Bruce’s vocal delivery is perfect here. He doesn't scream. He narrates. He sounds like a man lost at sea, watching these mythical events unfold from the deck of a crashing ship.

Ginger Baker’s Chaos Theory

While Clapton and Bruce were handling the melody, Ginger Baker was in the back doing what he did best: being absolutely terrifying on the drums. Most rock drummers in 1967 were playing a steady 4/4 beat. Not Ginger.

📖 Related: New Movies in Theatre: What Most People Get Wrong About This Month's Picks

In Tales of Brave Ulysses by Cream, the drumming is restless. It doesn't just keep time; it builds tension. Baker uses his tom-toms to create a rolling, thunderous sound that mimics the crashing of waves. He wasn't playing along to the song; he was playing against it, creating this weirdly beautiful friction. If you listen closely to the mono mix versus the stereo mix, you can hear how the drums panned across the speakers create a sense of disorientation. It’s intentional. It’s supposed to make you feel a little bit sea-sick.

Why the Disraeli Gears Sessions Mattered

This song was a highlight of the Disraeli Gears album. If you’re a gearhead or a music history nerd, you know that album title was a joke. A roadie named Mick Turner meant to say "derailleur gears" (bicycle parts) while talking to Clapton, but he messed up the words. The band thought it was hilarious.

The recording sessions at Atlantic Studios in New York were lightning fast. They only had a few days because of visa issues. This pressure cooked the tracks into something raw. There wasn’t time for over-polishing. That’s why Tales of Brave Ulysses by Cream feels so immediate. It’s a snapshot of three geniuses who barely liked each other but played together with a psychic connection.

The Legacy of the "Tiny Purple Fishes"

Some critics at the time thought the lyrics were a bit much. "Pretentious" was a word tossed around. But looking back, this song bridged the gap between the blues-rock of the early 60s and the progressive rock of the 70s. Without this track, you don't get Led Zeppelin’s "Achilles Last Stand." You don't get the sprawling, mythological epics of Rush or Iron Maiden.

👉 See also: A Simple Favor Blake Lively: Why Emily Nelson Is Still the Ultimate Screen Mystery

It also solidified the "Power Trio" format. Cream proved you didn't need five guys and a keyboard player to create a massive, symphonic sound. You just needed three people who were willing to push their instruments to the absolute breaking point.

How to Listen to It Properly Today

If you’re listening to a compressed MP3 on cheap earbuds, you’re missing half the song. To really get why this track is a masterpiece, you need to hear it on a decent setup.

- Find the Mono Mix: The stereo mix is fine, but the mono version has a punchiness in the bass and drums that feels like a physical hit to the chest.

- Focus on the Bass: Jack Bruce isn't just playing roots. He’s playing a counter-melody. His bass lines on this track are basically lead guitar parts in their own right.

- Ignore the Clock: Don't worry that it's short. Just let the atmosphere take over.

Tales of Brave Ulysses by Cream remains a masterclass in how to use technology (the wah-wah) and literature (Homer) to elevate a simple rock song into something eternal. It’s not just a relic of the Summer of Love; it’s a blueprint for every musician who wants to sound like they’re playing from the edge of the world.

Next time you're spinning some classic rock, skip the overplayed radio hits for a second. Put this on. Listen to that first cry of the guitar. You'll realize that even after sixty years, nobody has quite captured that specific brand of magic again.

To truly appreciate the evolution of this sound, track down a live bootleg from their 1968 tour. The studio version is tight, but the live improvisations on this track often stretched into ten-minute explorations that show just how much space those three musicians could fill.