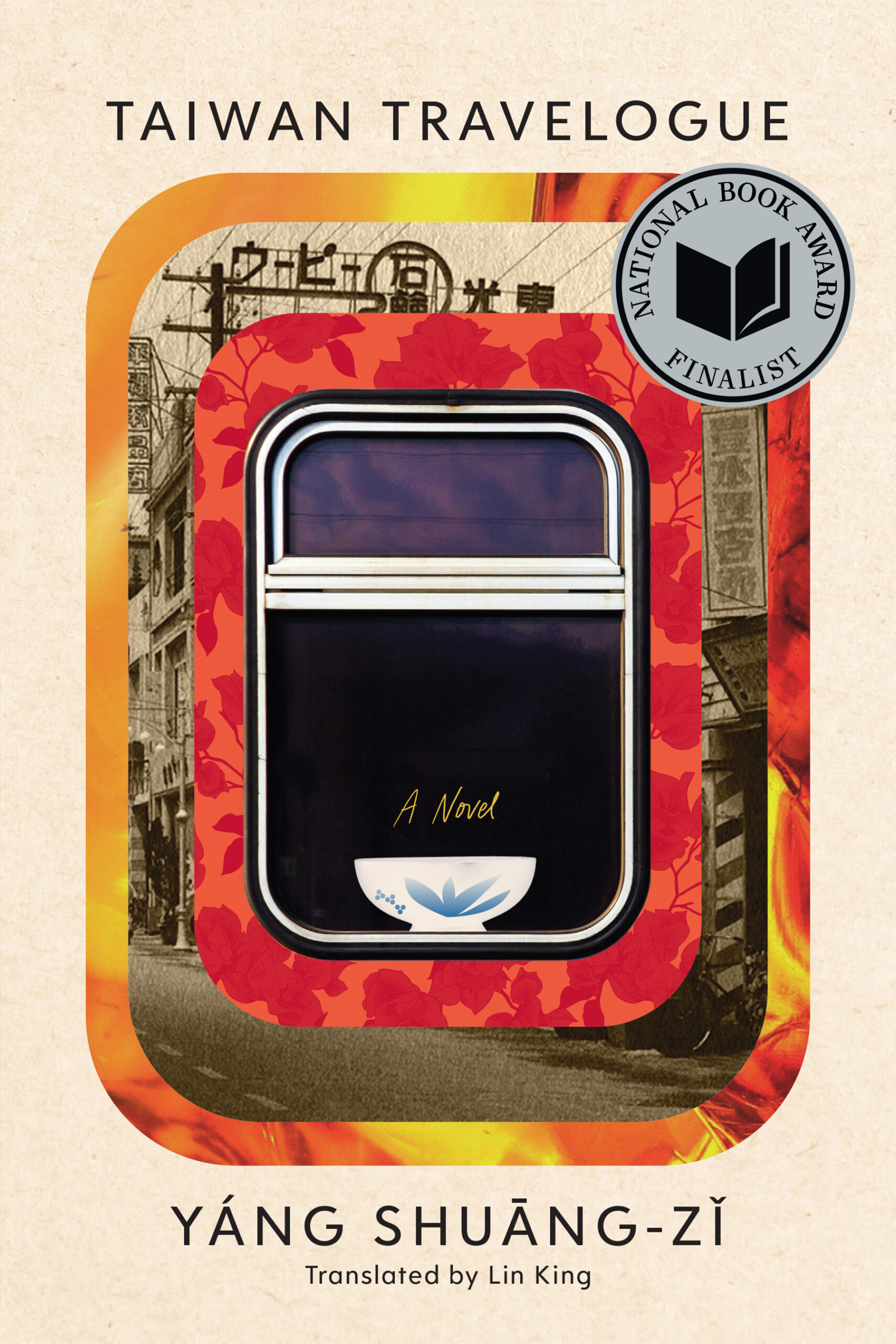

Maybe you’ve seen the cover—a vibrant, slightly vintage illustration of a woman in a high-collared dress—and thought it was just another cozy historical fiction. It isn't. Taiwan Travelogue: A Novel by Yang Shuang-zi (translated by Lin King) is a bit of a trickster. It presents itself as a long-lost memoir from the 1930s, written by a Japanese author named Chizuru Aoyama. But here’s the thing: Chizuru isn't real. The "translation" from Japanese to Chinese isn't a translation of an old text, but a contemporary masterpiece of metafiction. It’s a book about food, yes. It’s a book about friendship, sure. But mostly, it’s a book about the subtle, suffocating power of colonialism and how even the "kindest" people can be absolutely oblivious to the harm they cause.

I’ve spent a lot of time looking at how we talk about Taiwan’s history, and honestly, most Western readers only know the modern geopolitical headlines. This book changes that. It takes us back to the era of Japanese rule—a time of "modernization" that felt very different depending on whether you were the guest or the host.

What Actually Happens in Taiwan Travelogue: A Novel

The premise is straightforward. Chizuru Aoyama is a novelist from Japan who travels to Taiwan to find inspiration for her next book. She wants to see the "real" Taiwan, or at least the version of it she’s imagined in her head. She meets a local woman, Wang Qian-he, who becomes her interpreter and guide. They eat. They travel by train. They talk about literature. On the surface, it’s a travelogue. But if you look closer, the tension is thick.

Wang Qian-he is brilliant. She’s educated, speaks multiple languages, and knows the land intimately. Yet, because of the colonial hierarchy, she is effectively Chizuru’s servant. Chizuru thinks they are best friends. She thinks they are equals sharing a beautiful spiritual connection through gourmet food and high art. But the power dynamic is always there, lurking under the table like a ghost.

The Food Isn't Just Food

One thing you’ll notice immediately is the obsession with meals. We’re talking about detailed descriptions of dang-gui duck, pineapple, and elaborate banquets. Yang Shuang-zi uses food as a primary language. For Chizuru, the food is exotic and delightful—a novelty to be consumed. For the locals, it’s a matter of heritage and, sometimes, a performance for their Japanese overlords.

There is a specific scene involving a "tiffin" box that perfectly illustrates the disconnect. Chizuru views the shared meal as a romantic, platonic bonding experience. For the Taiwanese characters, it’s a navigation of etiquette and survival. You can almost feel the frustration of the characters who have to smile and nod while their culture is being treated like a theme park.

📖 Related: False eyelashes before and after: Why your DIY sets never look like the professional photos

Why This Book Is Messing With Your Head (In a Good Way)

What makes Taiwan Travelogue: A Novel so effective is the "translation" layer. The book includes a fictional translator’s note and a foreword that treat the story as a recovered historical artifact. This is a bold move. It forces the reader to question the reliability of the narrator.

Can we trust Chizuru? No. She’s a product of her time. She’s "enlightened" for a 1930s Japanese woman, but she still views Taiwan through a lens of superiority. She sees "progress" where there is actually displacement. By framing the book as a lost manuscript, Yang Shuang-zi forces us to confront how history is written. Usually, the colonizer gets to write the travelogue. The colonized just get to be the scenery.

The Real History Behind the Fiction

While the characters are fictional, the setting is meticulously researched. 1930s Taiwan was a place of massive transition. The Japanese had built a sophisticated railway system—which Chizuru uses extensively—and were pushing a policy of Kominka, which aimed to turn Taiwanese people into loyal subjects of the Emperor.

- The Railway Culture: The trains in the book aren't just for transport; they represent the "civilizing" mission of the Japanese Empire.

- Language Barriers: The interplay between Japanese, Hokkien, and other local dialects is a constant struggle for identity.

- Gender Roles: Both Chizuru and Qian-he are trying to carve out space in a patriarchal society, but their experiences are vastly different because of their ethnicity.

It’s easy to forget that Taiwan was Japan’s first colony. The relationship was complex. It wasn't just raw violence; it was "soft power" before that was even a term. Schools, hospitals, and infrastructure were used to justify the occupation. Taiwan Travelogue: A Novel digs into that "soft" side, showing how even a shared love for poetry can be an act of colonization.

Let’s Talk About That Ending (No Spoilers, I Promise)

The ending is what elevates this from a good book to a great one. It’s a gut punch. It recontextualizes everything you just read. You realize that Chizuru’s "beautiful friendship" with Qian-he wasn't what she thought it was. It’s a lesson in perspective.

👉 See also: Exactly What Month is Ramadan 2025 and Why the Dates Shift

If you’ve ever traveled to a place and thought you "got it" after a week, this book will make you cringe at your own past self. It challenges the idea of the "empathetic traveler." Sometimes, empathy is just another form of ego.

Why People Are Getting This Book Wrong

I’ve seen some reviews calling this a "lighthearted culinary journey." That’s a mistake. If you read it only for the recipes, you’re missing the point. It’s a tragedy disguised as a cookbook. The prose is often lush and inviting, which lulls you into the same sense of security that Chizuru feels. Then, the author pulls the rug out from under you.

The translation by Lin King deserves a massive amount of credit here. Translating a book that is about the act of translation and linguistic layers is a nightmare task. King manages to preserve the formality of the Japanese narrator while letting the underlying Taiwanese resentment simmer just beneath the surface.

Why You Need To Read It Right Now

Honestly, our world is still obsessed with travel narratives. We follow influencers who go to "undiscovered" places and claim to have found the "soul" of a culture. Taiwan Travelogue: A Novel is the antidote to that. It’s a sharp, witty, and heartbreaking reminder that we are always bringing our own baggage into someone else’s home.

If you’re interested in Asian history, queer subtext (there’s a lot of "the gaze" happening between the two women), or just damn good writing, this is it. It’s one of the few books that actually feels like it’s doing something new with the historical fiction genre.

✨ Don't miss: Dutch Bros Menu Food: What Most People Get Wrong About the Snacks

Actionable Next Steps for Readers

If you want to get the most out of Taiwan Travelogue: A Novel, don't just rush through it. Here is how to actually engage with the text and the history it represents:

Read the fictional paratext first.

Pay close attention to the "Translator's Introduction." It sets the stage for the deception. If you skip it, the middle of the book won't hit as hard because you won't realize the layers of artifice at play.

Look up the 1930s "Railway Hotels."

The book spends a lot of time in these grand, colonial institutions. Looking at archival photos of the Taipei Railway Hotel will give you a visual sense of the luxury Chizuru lived in compared to the reality of the streets outside. It helps bridge the gap between fiction and historical reality.

Track the mentions of "Native" vs "Civilized."

Every time Chizuru uses these words, take a second to ask what she’s actually describing. Usually, "native" means something she finds charmingly primitive, while "civilized" means something that looks like Japan. It’s a masterclass in how language is used to categorize people.

Listen to the audiobook or read aloud.

Because the book deals so much with the rhythm of language and translation, hearing the words can help emphasize the different "voices" that Yang Shuang-zi is mimicking.

Explore the "New Literature Movement."

The book references the intellectual climate of 1930s Taiwan. Researching real figures like Lai He or Loa Ho will give you a much deeper understanding of the resistance that was happening while fictional characters like Chizuru were busy writing poems about flowers.

The true value of this novel isn't just in its story, but in how it forces you to look at the "traveler" in yourself. It demands that you acknowledge the power dynamics in every room you enter. Once you finish that last page, you won't look at a travel blog the same way again.