If you ask any Formula 1 driver to name their favorite circuit, nine times out of ten, they’ll say Suzuka. It’s just facts. While newer tracks in Qatar or Miami feel like parking lots with neon lights, the Japan Grand Prix track is a brutal, old-school masterpiece carved into the Mie Prefecture landscape. It’s narrow. It’s fast. Honestly, it’s a bit terrifying if you’re hitting the 130R corner at 300km/h.

Most people don't realize that Suzuka wasn't even designed for racing cars initially. It was a Honda test track. Soichiro Honda basically told the Dutchman John Hugenholtz to build something world-class for testing motorcycles and cars back in 1962. Hugenholtz delivered the only "figure-eight" layout in the F1 calendar. Think about that for a second. The track literally crosses over itself with a massive overpass. It's the kind of engineering quirk you just don't see in modern "Grade 1" FIA tracks anymore because it's expensive and complicated to build.

The Brutality of the First Sector

The first sector of the Japan Grand Prix track is a relentless assault on a driver's neck muscles. You start with the high-speed Turn 1 and 2, which are basically one giant, decreasing-radius right-hander. If you miss the apex by even a few inches, you’re done. The momentum is gone.

Then comes the "S" Curves. This section is essentially a rhythm game. Drivers describe it like a dance—if you get the first left-hander wrong, you’re out of position for the next right, then the next left, and suddenly you’ve lost half a second before you’ve even reached the Degner curves. It’s high-downforce heaven. Sebastian Vettel famously loved this place, often calling it "God’s gift to racing." There’s no runoff. If you drop a wheel onto the grass here, you are heading straight for the foam blocks. No asphalt runoffs to save your ego here.

Why Degner 1 and 2 Scare the Pros

The Degner curves are named after Ernst Degner, a motorcycle racer who crashed there. They are short, sharp, and incredibly punishing. Degner 1 is a blind, fast right-turn that requires a huge amount of commitment. You flick the car in, pray the front end bites, and then immediately heavy-brake for Degner 2.

The curb at Degner 2 is a notorious car-breaker. If you take too much of it, the car gets unsettled and tosses you into the gravel trap. It’s a place where championships have been won and lost. You've got to be precise.

🔗 Read more: Cowboys Score: Why Dallas Just Can't Finish the Job When it Matters

The Mystery of the 130R and the Modern Era

We have to talk about 130R. The name comes from its radius—130 meters. Back in the day, this was the ultimate test of bravery. You approached it flat out, heart in your mouth, hoping the aero would hold you to the ground.

Today’s F1 cars have so much downforce that 130R is usually "easy" flat in dry conditions. But that doesn't mean it isn't dangerous. In 2002, Allan McNish had a horrific crash there that practically destroyed his Toyota. The corner was reprofiled slightly after that, but it still commands massive respect. Especially when the rain starts. And in Japan, the rain always starts eventually.

The Weather Factor at Suzuka

The Japan Grand Prix track is famous for its microclimate. You can have bright sunshine at the start-finish line and a monsoon at the Spoon Curve. Because it's located near Ise Bay, the humidity and sudden downpours are legendary.

We’ve seen some of the most dramatic wet-weather drives in history here. Remember 1994? Damon Hill driving the race of his life against Michael Schumacher in a literal deluge. Or the tragic 2014 race where the drainage simply couldn't keep up with the typhoon-strength rain. It’s a fickle place. The track surface is quite abrasive, too, which means when it’s wet, it’s slippery, but when it dries, it eats tires for breakfast.

Why the Fans Make the Japan Grand Prix Track Unique

You can't talk about the track without talking about the people in the grandstands. Japanese F1 fans are on a different level. You’ll see people wearing hats with functioning DRS flaps or 1:1 scale replicas of Ayrton Senna’s helmet made out of cardboard. They stay in the stands for hours after the sessions just to watch the mechanics clean the garages.

💡 You might also like: Jake Paul Mike Tyson Tattoo: What Most People Get Wrong

This energy feeds into the weekend. Most drivers arrive in Japan feeling exhausted from the long season, but the enthusiasm in Suzuka is infectious. It’s one of the few places where every single driver on the grid feels like a rockstar.

The Technical Challenge: Finding the Balance

Setting up a car for the Japan Grand Prix track is a nightmare for engineers. You need:

- High downforce for the S-Curves and Sector 1.

- Low drag for the long run from Spoon Curve through 130R to the Casio Triangle.

- Suspension that can handle the violent curb-striking at the chicane.

Usually, teams have to compromise. If you run too much wing, you’re a sitting duck on the straights. If you run too little, the car is "pointy" and nervous through the fast stuff, which kills the tires. It’s a delicate balancing act that separates the top-tier teams from the midfield.

Misconceptions About the Figure-Eight

People often think the crossover means the track is dangerous because cars could somehow collide. Obviously, that's not how bridges work. What the figure-eight actually does is balance out tire wear. Most tracks go clockwise or counter-clockwise, meaning one side of the car takes a beating. At Suzuka, because of the crossover, you have an almost equal number of left and right-hand turns.

Actually, it's 10 right-handers and 8 left-handers. This makes it one of the most physically demanding tracks for the drivers' necks because they're being pulled in both directions constantly. Most tracks just destroy one side of your body. Suzuka is an equal-opportunity punisher.

📖 Related: What Place Is The Phillies In: The Real Story Behind the NL East Standings

What to Watch for in 2026 and Beyond

As F1 moves toward the 2026 regulations with more emphasis on electrical power and active aerodynamics, Suzuka is going to get even more interesting. The heavy braking at the Casio Triangle (the final chicane) is the primary spot for energy recovery.

If a driver messes up the exit of Spoon Curve—which is a long, double-apex left-hander that feels like it goes on forever—they won't have the battery deployment to defend down the long back straight. It turns the final sector into a tactical chess match.

The move of the Japan Grand Prix to a springtime slot (April) has also changed the game. Usually, we were used to Suzuka being a title-decider in the autumn. Now, it’s an early-season test of true aerodynamic efficiency. The cooler temperatures in April mean the engines breathe better, but getting heat into the tires for a qualifying lap becomes a massive headache.

Actionable Insights for Following the Japan Grand Prix

To truly appreciate the Japan Grand Prix track, stop watching the leader and start watching the "onboard" cameras during Sector 1. Look at the steering inputs through the S-Curves. A smooth driver will have minimal corrections; if you see the steering wheel "sawing" back and forth, they’ve lost the rhythm and their lap time is dead.

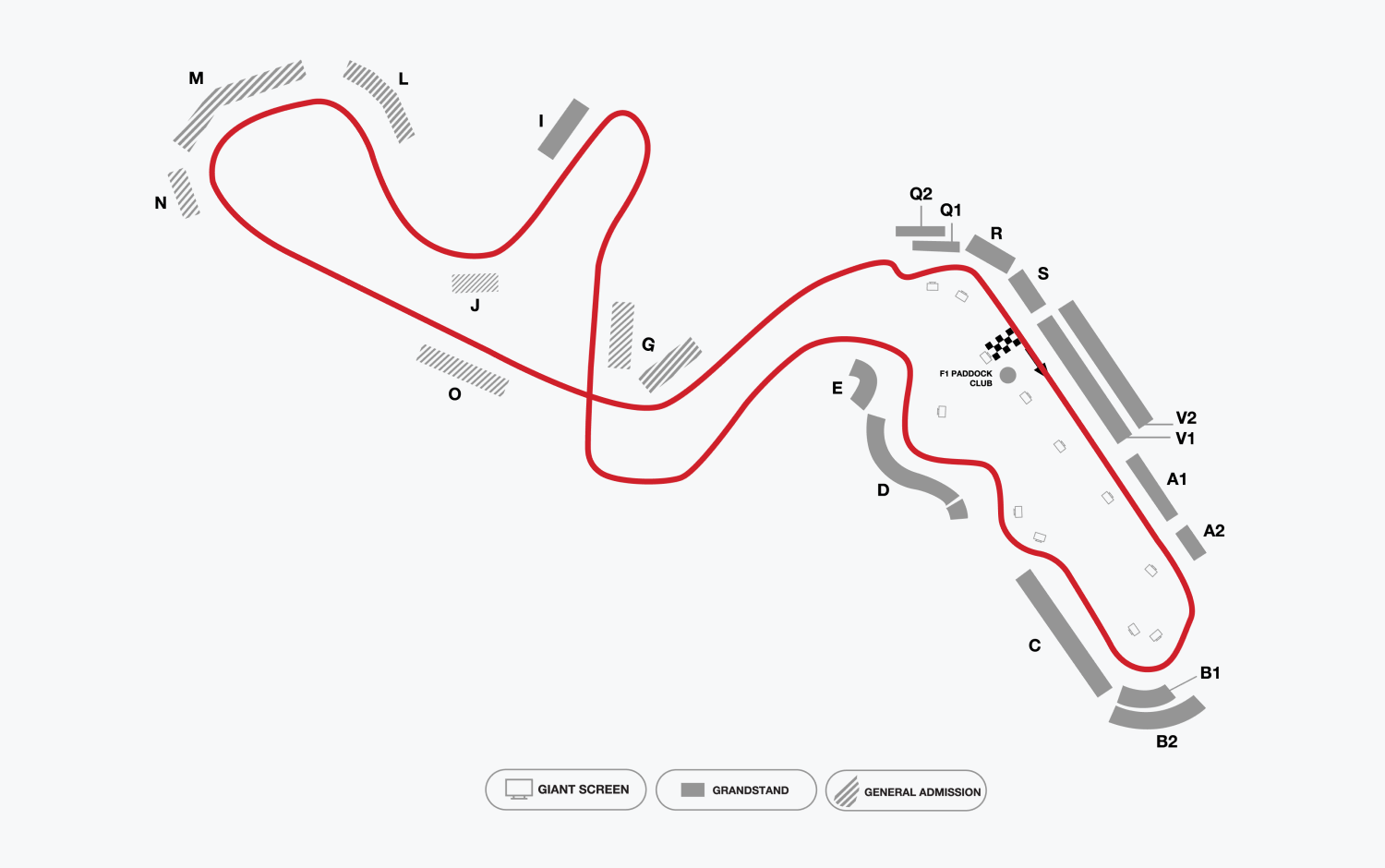

If you are planning a trip to the track, aim for seats at the Q2 grandstand. It overlooks the entry to the S-Curves and gives you the best view of the sheer change of direction these cars are capable of. Also, buy your merchandise on Thursday. By Friday afternoon, anything with a popular driver's name on it will be sold out.

Lastly, pay attention to the "Casio Triangle" chicane at the end of the lap. It’s the only real overtaking spot on the track. Almost every iconic Suzuka moment—from the Senna/Prost collisions to Kamui Kobayashi’s legendary 2012 podium—happened because of a desperate lunging move into that tight right-left flick. It’s where the bravery of the fast sectors meets the cold reality of hard braking.