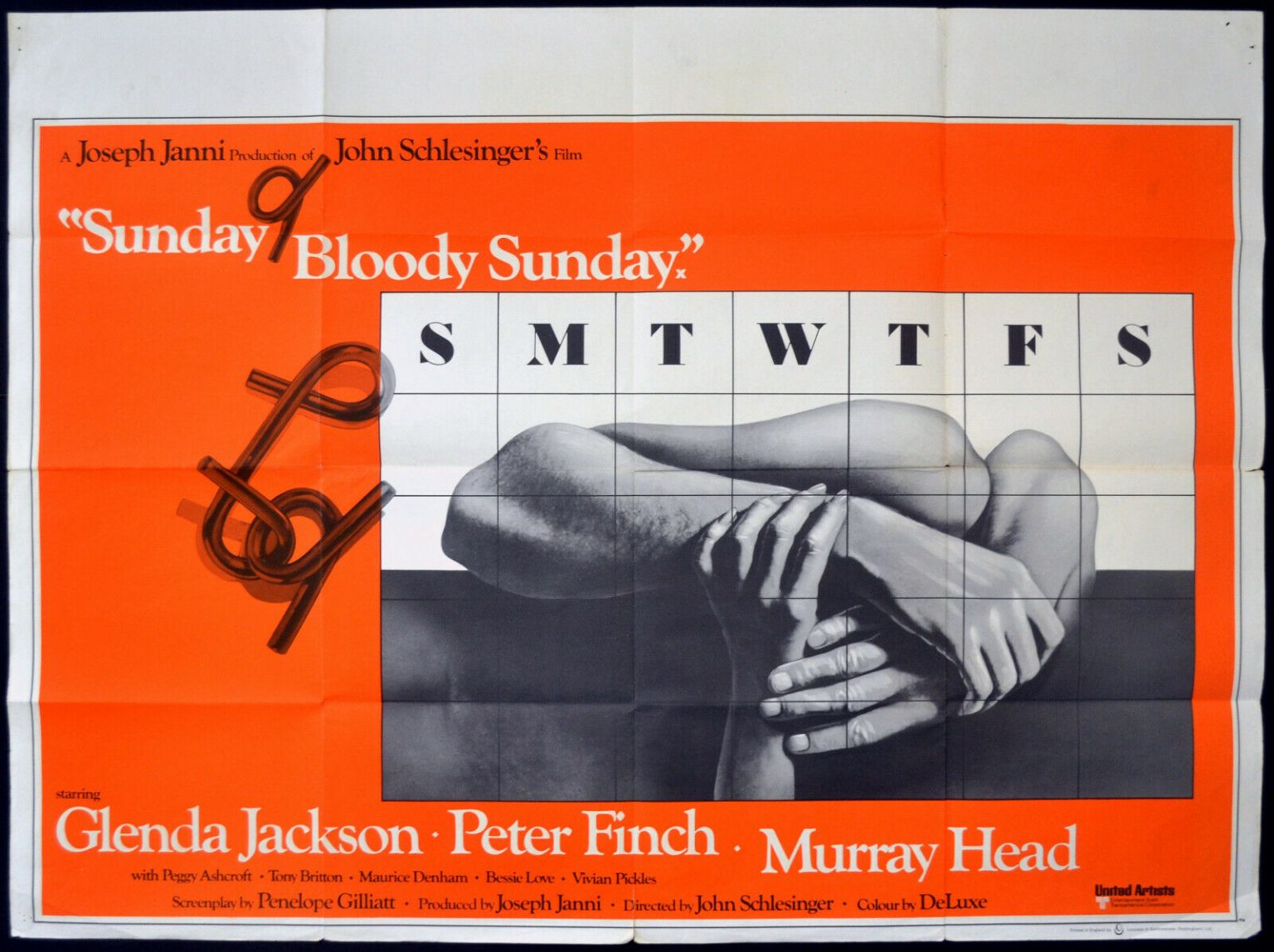

It’s easy to forget how radical a movie could be fifty years ago. People think of the seventies in Hollywood as a gritty, sweat-soaked era of Scorsese and Coppola, but over in London, John Schlesinger was making something entirely different. He made Sunday Bloody Sunday. It’s a film about a love triangle, sure, but it’s not the kind you see on Netflix today where everyone is screaming and throwing drinks. It’s quiet. It’s devastating. Honestly, it’s probably the most "grown-up" movie I’ve ever seen.

The story centers on two people—Daniel Hirsh, a middle-aged Jewish doctor, and Alex Greville, a frustrated recruitment consultant—who are both in a relationship with the same man. That man is Bob Elkin, a young, somewhat flighty kinetic artist who treats both of them with a sort of casual, breezy affection that is maddening.

What Most People Get Wrong About Sunday Bloody Sunday

If you look up the Sunday Bloody Sunday film online, you’ll see it frequently cited as a "pioneering queer film." And it is. But calling it that almost does it a disservice because it suggests the movie is about being gay. It isn’t. Not really.

Peter Finch plays Dr. Hirsh, and Glenda Jackson plays Alex. They both know about the other. They don't like it, obviously, but they accept it because they’d rather have a piece of Bob than nothing at all. That’s the core of the movie. It’s about the compromises we make just to avoid being alone on a drizzly Sunday afternoon in London.

The Famous Kiss

There is a moment early in the film where Daniel and Bob kiss. In 1971, this was a massive deal. It wasn't a "statement" kiss or a tragic, shameful moment. It was just two men who cared about each other saying hello. Schlesinger, who was gay himself, fought to keep the tone matter-of-fact. He didn't want the audience to pity Daniel. He wanted them to recognize his hunger for connection.

It's weirdly modern.

You’ve got a protagonist who is successful, respected, and Jewish, whose sexuality is just one part of his identity. That was unheard of back then. Most gay characters in cinema at the time were either villains, victims, or the "funny friend" who dies by the third act. Daniel Hirsh is just a guy trying to manage a busy medical practice while his heart is being slowly broken by a guy who’s halfway out the door.

The Penelope Gilliatt Script and the London Fog

The screenplay was written by Penelope Gilliatt, who was a film critic for The New Yorker. You can feel her sharp, observant eye in every line of dialogue. She didn't write "movie lines." She wrote the way people actually talk when they’re trying to be polite while their lives are falling apart.

📖 Related: Gwendoline Butler Dead in a Row: Why This 1957 Mystery Still Packs a Punch

London in the film isn't the "Swinging Sixties" version with colorful buses and Mini Coopers. It’s drab. It’s post-imperial. It’s full of power cuts and ringing telephones. The telephone is actually a huge part of the movie. Everything happens through the "Belsize Park Telephone Answering Service." It’s this mechanical intermediary that connects—and separates—the lovers.

- The pacing is slow. It breathes.

- The cinematography by Billy Williams uses these muted, cold colors that make the interiors feel like sanctuaries against the gray world outside.

- The acting is unparalleled. Peter Finch wasn't the first choice—Ian Bannen was, but he supposedly got cold feet about the role—but Finch brings this soulful, weary dignity to the doctor that is just haunting.

Glenda Jackson is equally incredible. She’s brittle. She’s smart. She knows Bob is going to leave her, and she’s already mourning him while he’s still in her bed.

Why the Ending of the Sunday Bloody Sunday Film Matters So Much

Most romances end with a big choice. The protagonist picks a side, or they find a new person, or they realize they’re better off alone.

This movie doesn’t do that.

Bob eventually decides to move to New York. He leaves them both. The final scene features Peter Finch breaking the "fourth wall." He looks directly at the camera and talks to us. He talks about how people say he’s better off without Bob, and how he should have more pride.

"But I am happy," he says. "Apart from missing him."

That line? It’s a gut punch. It acknowledges that sometimes, a half-measure of love is better than no love at all. It’s a direct challenge to the idea that we all need "closure" or "perfect relationships" to be whole.

👉 See also: Why ASAP Rocky F kin Problems Still Runs the Club Over a Decade Later

Real-World Impact and Legacy

When the Sunday Bloody Sunday film was released, it wasn't a massive blockbuster, but it hit the Oscars hard. It got four major nominations: Best Director, Best Actor, Best Actress, and Best Original Screenplay. It’s one of the few movies to get those four nods without being nominated for Best Picture.

Critics like Roger Ebert gave it four stars, noting that it was a movie about "the difficulty of being human."

But honestly, the real impact is how it influenced filmmakers like Todd Haynes or Andrew Haigh. You can see the DNA of this movie in something like Weekend (2011) or All of Us Strangers. It’s that same interest in the quiet, domestic spaces where we try to build a life.

Technical Mastery and the "Schlesinger Touch"

John Schlesinger was coming off the massive success of Midnight Cowboy. He had all the power in the world, and he chose to use it to make a small, personal film about middle-class Londoners.

He uses these "interstitial" shots of the city—demolition sites, children playing in the street, dogs—that make the movie feel like a documentary. It’s not "slick." There are scenes that feel improvised, even though they were meticulously planned.

- The Sound Design: There is very little music. Most of what you hear are the sounds of the city, the hum of the heater, or a Mozart opera playing on a record player in the background.

- The Absence of Melodrama: When Alex finds out Bob has been with Daniel, she doesn't scream. She goes to the kitchen. She tries to keep her dignity. It’s much more painful to watch than a screaming match.

- The Jewish Identity: The film depicts Daniel’s Jewish family life with incredible detail. The Bar Mitzvah scene isn't a caricature; it’s a warm, suffocating, realistic portrayal of family expectations.

Basically, it's a film about the 1970s that doesn't feel like a period piece. It feels like it could be happening next door.

Actionable Insights for Modern Viewers

If you haven't seen it, or if you're a film student looking to understand "Kitchen Sink Realism" mixed with high-concept drama, here is how to approach it.

✨ Don't miss: Ashley My 600 Pound Life Now: What Really Happened to the Show’s Most Memorable Ashleys

Watch the eyes.

The performances in this movie happen in the silences. Watch Glenda Jackson’s face when she’s watching Bob sleep. She’s calculating the seconds until he leaves.

Don't look for a hero.

Bob Elkin isn't a villain. He’s just young and a bit selfish. He’s the catalyst, not the protagonist. If you go in expecting someone to be "right," you’ll miss the point.

Contextualize the "Sunday."

In 1970s England, Sunday was a dead day. Everything was closed. It was a day of forced reflection and family obligations. The "Bloody Sunday" of the title isn't about violence; it’s about the crushing boredom and loneliness that hits when the world stops moving for twenty-four hours.

Find the Criterion Collection version.

If you can, get the restored version. The colors and the sound design are crucial to the experience. It captures a specific "London blue" that is lost in low-quality streams.

This film remains a masterclass in empathy. It tells us that we don't have to be perfect to be worthy of a story. It tells us that love is often messy, shared, and incomplete—and that's okay. In a world of "happily ever afters" or "dark tragedies," Sunday Bloody Sunday sits right in the middle. It’s just life.

Next Steps for Film Enthusiasts:

- Compare this to Schlesinger’s Midnight Cowboy to see how he handles urban loneliness in two different cultures.

- Research the work of Penelope Gilliatt; her film criticism often informed her sharp, unsentimental approach to screenwriting.

- Observe the "breaking the fourth wall" technique in the final monologue; it’s one of the few times in cinema history where it feels completely earned and not like a gimmick.