Stephen King was nearly dead when he finished the second half of this book. He was walking along a road in Maine, a van hit him, and suddenly the guy who spent decades inventing nightmares was living one. His lungs were collapsed. His leg was shattered in about nine places. Most people would have just retired and called it a day. But King got back to the desk because, as he puts it in On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft, writing isn't just a job—it’s a support system for life.

Honestly, most "how-to" books on writing are garbage. They’re filled with flowery metaphors about "finding your muse" or some nonsense about the hero's journey that feels like a middle school textbook. King doesn’t do that. He treats writing like carpentry. You have a toolbox. You have a job to do. You get the job done. It’s that simple, and it’s also that incredibly difficult.

The Toolbox: What Most People Get Wrong

People think they need a fancy office or a $3,000 MacBook to be a "real" writer. King says you need a door you can close. That’s basically it. He spends a huge chunk of the book talking about the "toolbox," a concept he inherited from his Uncle Oren. You carry this metaphorical box around with you, and it’s got layers.

The top layer? Vocabulary.

Don't try to be smart. This is where most beginners fail. They use words like "remonstrate" when they just mean "argued." King’s advice is brutal: use the first word that comes to mind, if it’s appropriate and colorful. If you start digging for big words because you’re embarrassed by your small ones, you’re lying to the reader. Readers smell a liar a mile away.

Then there’s grammar. He doesn't want you to be a scholar, but you need to know the basics so you don't look like an idiot. He famously hates the passive voice. "The rope was thrown by John" is weak. "John threw the rope" is strong. It’s about energy. If your sentences are passive, your story is passive. Your reader falls asleep. You lose.

Adverbs are the Path to the Dark Side

If there is one thing On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft is known for, it’s King’s absolute, unyielding hatred for adverbs. You know the ones. They end in "-ly."

He ran quickly. She said timidly.

💡 You might also like: Greatest Rock and Roll Singers of All Time: Why the Legends Still Own the Mic

King argues that using an adverb is usually a sign that the writer is afraid they aren't expressing themselves clearly. It's a "clump of dandelions" in your lawn. If you have to tell us someone said something "threateningly," your dialogue should have already told us that. If the dialogue is good, the adverb is redundant. If the dialogue is bad, the adverb won't save it.

He’s not saying never use them. He’s saying they’re a crutch. Throw the crutch away and see if your prose can stand on its own two feet. It’s scary, but it works.

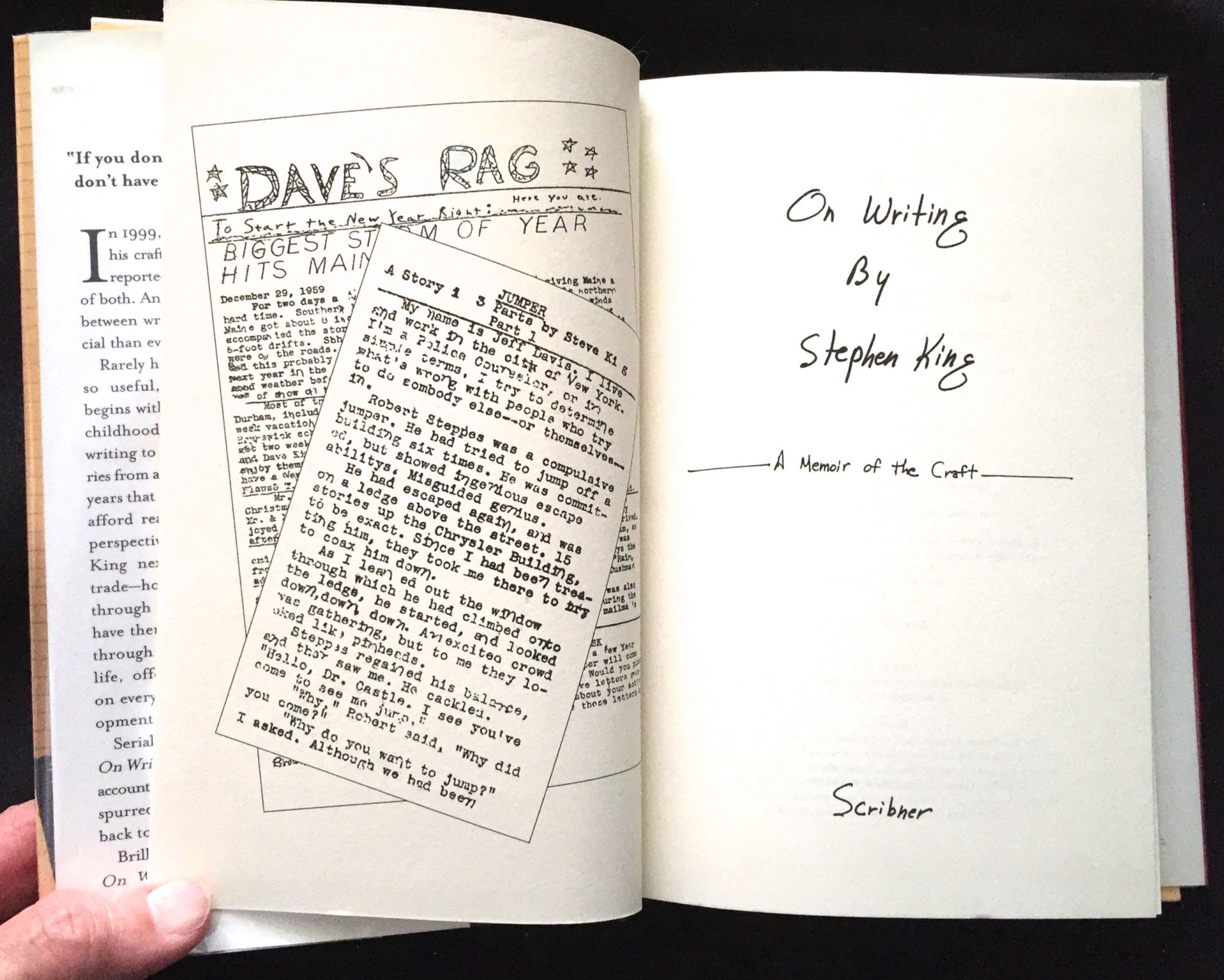

The "Memoir" Part: Poverty, Rejection, and a Bloody Spike

The first half of the book isn't technical at all. It’s a memoir. It covers his childhood, his weird obsession with horror comics, and the years he spent living in a double-wide trailer with his wife, Tabitha, working as a laundry janitor and teaching English.

They were broke. Seriously broke.

King used to pin his rejection slips to a nail in his wall. When the nail couldn't hold the weight of the paper anymore, he replaced it with a spike and kept going. That’s the reality of the craft. It isn’t about being "discovered" at a Starbucks. It’s about the spike.

The story of how Carrie came to be is legendary for a reason. King hated the first few pages. He thought he couldn't write from a teenage girl's perspective. He literally threw the manuscript in the trash. Tabitha fished it out, wiped off the cigarette ashes, and told him he had something. If she hadn't done that, Stephen King would probably be a retired schoolteacher in Maine right now, and we’d have never heard of Cujo or Pennywise.

Forget Plot, Focus on the Situation

Here is the most controversial take in the whole book: King doesn't believe in "plotting."

📖 Related: Ted Nugent State of Shock: Why This 1979 Album Divides Fans Today

He hates outlines. He thinks they are the enemies of spontaneity. To him, a story is like a fossil in the ground. Your job as a writer isn't to create the fossil; it’s to dig it out as carefully as possible without breaking it.

He starts with a "what if."

- What if a writer is held captive by his "number one fan"? (Misery)

- What if a town is suddenly cut off by an invisible dome? (Under the Dome)

Once you have the situation, you just let the characters react. You don't force them into a pre-planned ending. If you do, the characters start feeling like puppets. The reader notices. The "dream" of the story breaks. King’s approach to On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft emphasizes that the characters should dictate the ending, even if it surprises the author.

The Sacred Desk

King writes every day. Every. Single. Day. Christmas, his birthday, July 4th. He aims for 2,000 words a day. That’s about ten pages.

If you don't have time to read, you don't have the time (or the tools) to write. He’s very clear on that. You should be reading about 4-6 hours a day and writing for another 2-4. If that sounds like too much, he basically suggests you might want to find a different hobby. It’s a blue-collar approach to an art form that people often treat as something mystical. It’s not mystical. It’s labor.

Why This Book Still Matters in the Age of AI

We live in a world where you can ask a chatbot to write a story about a haunted toaster in three seconds. So why read a book from 2000 about the "craft"?

Because AI is the ultimate "passive voice" machine. It’s the king of adverbs. It’s the definition of "lying to the reader" because it doesn't actually feel anything. King’s book is about human connection. It’s about the "telepathy" that happens when a writer puts a word on a page and a reader, maybe a hundred years later, picks it up and feels exactly what the writer felt.

👉 See also: Mike Judge Presents: Tales from the Tour Bus Explained (Simply)

You can’t faked that. You can't prompt that into existence.

King talks about the "Boys in the Basement." This is his metaphor for the subconscious mind. The basement is where the real creative work happens while you're busy doing the manual labor of typing. AI doesn't have a basement. It only has a processor.

Acknowledging the Limitations

Is King always right? Probably not.

Literary critics have spent decades pointing out that his endings can be... well, a bit messy. That’s the risk of not plotting. Sometimes the fossil you dig up is missing a tail or has two heads. If you follow King's advice to the letter, you might find yourself 400 pages into a book with no idea how to finish it.

Also, his "no adverbs" rule is a bit hyperbolic. If you read his early stuff, like The Stand, he uses adverbs all the time. He’s softened his style as he’s aged. But as a teaching tool? His "strict" rules are exactly what a messy, unorganized writer needs to hear to tighten up their prose.

Actionable Steps for Your Own Writing

Don't just read the book and put it on a shelf. If you want to actually use the lessons from On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft, you need to change your workflow immediately.

- Kill your darlings. If you have a sentence you love because it sounds "poetic" but it doesn't actually move the story forward, delete it. It’s hard. Do it anyway.

- The 10% Rule. King suggests that your second draft should be your first draft minus 10%. Edit for pace. If it feels slow to you, it feels like a marathon to the reader.

- Set a "Meters" Goal. Don't wait for inspiration. Set a word count. Whether it’s 500 words or 2,000, don't leave the chair until you hit it.

- Close the door. Write the first draft with the door closed—this is for you. Rewrite with the door open—this is for the reader.

- Read bad books. King says reading great writing is inspiring, but reading bad writing is actually more educational. It shows you exactly what not to do and gives you the confidence that "Hey, I can do better than this."

The ultimate takeaway from King isn't about how to be a bestseller. It’s about the fact that writing can save your life. It can be a way to process trauma, a way to understand the world, and a way to stay sane when things go sideways.

Pick up a pen. Sit down. Start digging for the fossil.

Next Steps for Mastery:

Begin by identifying your "writing space." It doesn't need to be pretty, but it must be consistent. Eliminate all distractions—phones in another room, no internet—and commit to a "Door Closed" policy for exactly sixty minutes today. During this hour, ignore the quality of the prose and focus entirely on the "situation" of your story, allowing your characters to move without an outline. Once finished, perform a "clump of dandelions" check: find every adverb ending in -ly and delete at least half of them to see if the verbs can carry the weight on their own.