You've seen him. Honestly, we all have. He’s that minimalist little guy—a circle for a head, five thin lines for a body—stuck in a perpetual state of "just existing." When we talk about status quo pictures of matchstick man, we aren't just talking about a crude doodle on a cocktail napkin. We are talking about the ultimate visual shorthand for the human condition.

He’s the everyman.

Think about the last time you saw a safety manual or a "Caution: Wet Floor" sign. That’s him. He’s slipping. He’s falling. He’s standing perfectly still to represent a "default" person. In a world obsessed with 4K resolution and hyper-realistic AI-generated avatars, the matchstick man (or stick figure, if you’re being informal) remains the king of communication. Why? Because he lacks ego. He lacks race, gender, and social class—unless we specifically draw a hat or a skirt on him. He is the "status quo" because he represents everyone and no one simultaneously.

The Psychology of the Minimalist Human Form

Why does a stick figure work? It’s kinda weird when you think about it. We are biological masterpieces of bone, muscle, and skin, yet we look at five lines and a dot and say, "Yeah, that’s a guy."

Cognitive psychologists call this "top-down processing." Our brains are wired to find human patterns in everything—it’s the same reason people see Jesus in a piece of toast. When we look at status quo pictures of matchstick man, our brains fill in the blanks. We don't see lines; we see intention. If the legs are angled, he’s running. If the head is tilted, he’s thinking.

Scott McCloud, in his seminal work Understanding Comics, explains this perfectly. He argues that the more "cartoony" or simplified a face is, the more people can describe themselves within it. A detailed photograph is a specific person (not you). A stick figure is a vacuum that we crawl into. It’s the baseline of human identity. That is the definition of the status quo in visual design: the point from which all other variations deviate.

Why We Keep Drawing the Same Guy

There is a certain comfort in the familiar.

✨ Don't miss: Am I Gay Buzzfeed Quizzes and the Quest for Identity Online

If you search for status quo pictures of matchstick man, you’ll find a recurring theme: stability. In corporate presentations, he’s often used to show "The Way Things Are" versus "The Way Things Could Be." He is the anchor.

- Universality: You don't need a translator to understand a stick figure. A matchstick man pushing a boulder speaks the same language in Tokyo as he does in New York.

- Speed: In a fast-paced digital world, the status quo is about efficiency. You can draw a matchstick man in three seconds. You can’t do that with a realistic portrait.

- Focus: By stripping away the "noise" of hair color or clothing brands, the artist forces the viewer to focus on the action or the emotion.

It’s almost like the matchstick man is the "Helvetica" of people. He’s clean. He’s functional. He’s been around since the cave paintings in Lascaux and he isn't going anywhere. Honestly, he’s probably the most successful "design" in human history.

The Matchstick Man in Modern Art and Social Commentary

Don't mistake simplicity for a lack of depth. Some of the most poignant social commentaries use status quo pictures of matchstick man to drive a point home.

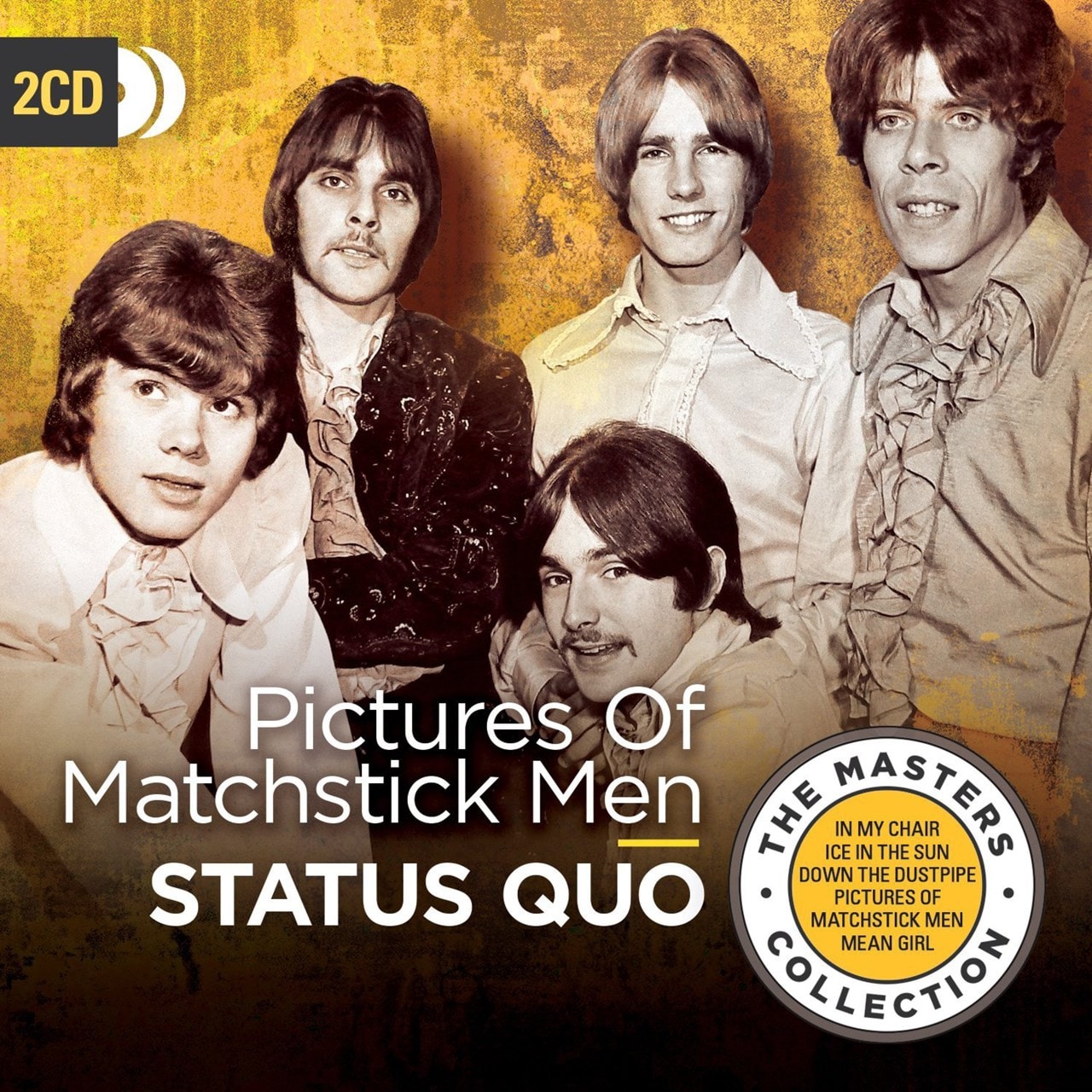

Take the works of L.S. Lowry, for instance. The English artist was famous for his "matchstalk men" (as the song goes). He painted the industrial North of England, filling his canvases with thousands of these figures. To Lowry, the matchstick man wasn't just a shortcut; it was a way to show the scale of the industrial revolution. The individuals were tiny, fragile, and identical, swallowed up by the massive mills and smoky skies. He used the status quo of the human form to highlight the loss of individuality in a machine-driven world.

Then you have modern webcomics like xkcd by Randall Munroe. Munroe uses stick figures to explain incredibly complex topics—orbital mechanics, relational database management, or the existential dread of a dying star. By using a "status quo" visual style, he makes the high-level science feel accessible. If a stick figure can understand string theory, maybe we can too.

It’s a brilliant subversion. We expect the matchstick man to be basic, so when he says something profound, it hits harder.

🔗 Read more: Easy recipes dinner for two: Why you are probably overcomplicating date night

The Digital Evolution: Is the Status Quo Shifting?

We’re in 2026. Things are changing.

We have VR, AR, and haptic suits. You’d think the matchstick man would be dead by now. But look at your phone. Look at your emojis. The "standard" person emoji is essentially a stylized, colorful version of the matchstick man. Even in gaming, the "status quo" often returns to simplicity. Look at the massive success of games like West of Loathing or various indie titles on Steam that use stick-figure aesthetics.

They use this style because it’s "meta." It’s a nod to the early days of the internet—think Stick Death or Xiao Xiao animations from the early 2000s. For a certain generation, the matchstick man isn't just a sign; he’s nostalgia. He represents the "status quo" of the early web, a time when creativity was limited by bandwidth but not by imagination.

Breaking the Mold: When the Matchstick Man Rebels

Sometimes, the power of status quo pictures of matchstick man comes from breaking the rules.

What happens when the stick figure stops behaving? In many viral animations, the joke is that the "status quo" figure suddenly gains 3D physics or starts interacting with the UI of the software he was drawn in. This "breaking of the fourth wall" only works because we have such a rigid expectation of what a stick figure is supposed to do. He’s supposed to stay in his lane. He’s supposed to be a static symbol.

When he moves like a human, or shows complex emotion, it creates a "cognitive itch." It’s a reminder that even the most basic symbols carry the weight of our humanity.

💡 You might also like: How is gum made? The sticky truth about what you are actually chewing

Practical Ways to Use the "Everyman" Aesthetic

If you're a creator, designer, or just someone trying to explain a point, don't sleep on the matchstick man. He’s a tool.

- For Brainstorming: Don't get bogged down in details. Use stick figures to storyboard your ideas. If the story works with matchstick men, it will work with high-res actors.

- For Communication: If you’re giving a presentation, a hand-drawn stick figure can actually be more engaging than a stock photo. It feels more "human" and less "corporate."

- For Accessibility: Remember that the status quo is about being understood. If your icons are too complex, people will get lost. Stick to the basics.

The matchstick man is the ultimate survivor. He has outlasted art movements, technological revolutions, and cultural shifts. He is the visual "baseline" of our species.

Next time you see a status quo picture of matchstick man, don't just see a lazy drawing. See the thousands of years of human history, psychology, and design theory that led to those five simple lines. He is us, stripped of our pretenses, standing there in the middle of the page, waiting for us to decide what he does next.

Actionable Insights for Using Minimalist Visuals

To make the most of this "status quo" aesthetic in your own projects, focus on posture and proportion. Even without a face, a matchstick man can convey deep sadness by slightly curving the vertical "spine" line or joy by lifting the "arm" lines above the head. Focus on the negative space around the figure; a small matchstick man in a large white void immediately communicates loneliness or insignificance. Finally, use line weight to imply importance—a thicker line for the "status quo" figure makes him feel grounded and permanent, while thinner lines can make him seem fleeting or ghostly. By mastering these tiny nuances, you can turn a basic doodle into a powerful storytelling device.

Source References & Further Reading:

- McCloud, S. (1993). Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. (Discussion on the "masking effect" and iconicity).

- Gombrich, E.H. (1960). Art and Illusion. (On how we interpret simplified forms).

- The Lowry Collection, Salford Quays. (Historical context on the use of matchstick figures in industrial art).