If you were standing in a muddy field in 2006, maybe in New Orleans or at a rainy festival in Europe, you heard it. A raucous, brassy, stomp-along anthem that sounded less like a rock star and more like a drunken street parade. Springsteen Pay Me My Money Down isn’t just a cover song. It’s a weird, essential pivot point in Bruce Springsteen’s career where the guy who wrote "Born to Run" decided to stop being a "Boss" for a second and start being a folk historian.

Honestly, the first time people heard it, some were confused. This was Bruce? Where were the Telecasters? Where was the E Street Band? Instead, we got banjos and a trombone section that sounded like it was fueled by cheap whiskey. But the song stuck. It became a live staple because it taps into something primal.

The Accidental Protest Anthem

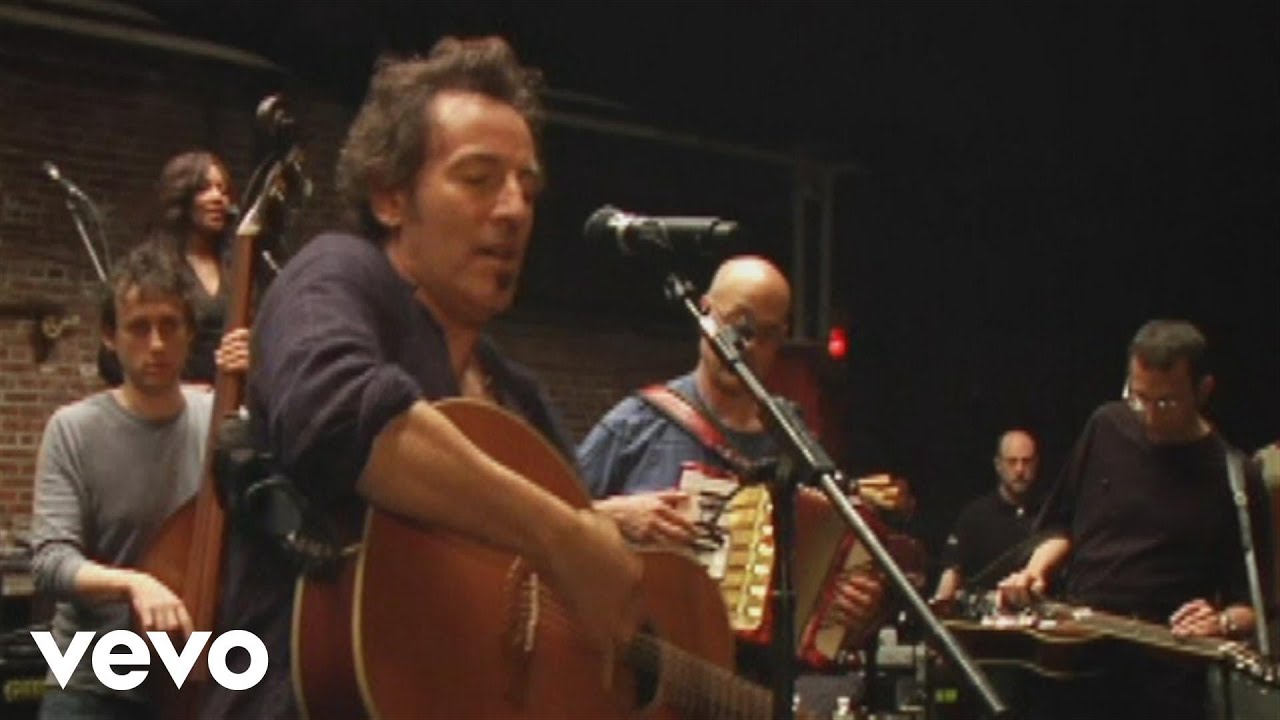

The track originally appeared on We Shall Overcome: The Seeger Sessions. That album was a massive risk. At the time, Springsteen was coming off Devils & Dust, a quiet, solo acoustic record. Everyone expected him to go back to the stadium rock sound. Instead, he gathered a group of musicians in his farmhouse—people who barely knew each other—and recorded a bunch of old folk songs popularized by Pete Seeger.

Springsteen Pay Me My Money Down is actually a "shanty." It’s a work song. Originally, it was sung by Black stevedores working the docks in the Georgia Sea Islands. Imagine men hauling massive loads of timber or cotton, singing to keep the rhythm. The lyrics are dead simple. A captain is trying to stiff a worker. The worker isn't having it.

The Gullah people of the South Carolina and Georgia coast are the ones who kept this song alive. It was collected by folklorists like Lydia Parrish in the early 20th century. When Springsteen grabbed it, he didn't try to make it "authentic" in a museum sense. He made it a party. But beneath that party is a very real, very angry demand for fair wages. It’s about the basic dignity of getting paid for your sweat.

Why the 2006 Arrangement Works

The arrangement is basically a New Orleans Second Line. It’s chaotic. If you listen closely to the studio version, you can hear Bruce shouting instructions to the band. He’s yelling "horns!" and "trombones!" because they were basically recording it live in a room.

There's no polish. That's the point.

One of the coolest things about the Seeger Sessions Band was the sheer volume of sound. You had the Soozie Tyrell violin, the Charlie Giordano accordion, and a brass section that just wailed. Most Springsteen songs are carefully built layers. This one? It’s a landslide. It’s got that "oom-pah" rhythm that makes it impossible to stand still.

- The tempo is faster than most traditional versions.

- The call-and-response vocal is designed for a crowd of 50,000 people to shout back.

- The lyrics are repetitive, which is a classic folk trope.

It’s actually kinda funny how a song about being broke and cheated by a ship captain became a massive hit for a multi-millionaire rock star, but that’s the power of folk music. It transcends the individual.

💡 You might also like: Why This Is How We Roll FGL Is Still The Song That Defines Modern Country

The Lyrics: A Deep Dive Into the Conflict

Let's look at what's actually happening in the song. The narrator is a deckhand. He’s been working the "lowlands." He’s ready to go home, but the captain is holding out.

"I went to the Boss, but the Boss was gone..."

There is a beautiful irony in Bruce Springsteen singing about going to "the Boss" and finding him missing. The song describes a specific kind of frustration. You've done the work. The ship is ready to sail. But you’re being cheated out of your "pocketful of money."

The line "forty nights at sea" gives you the scope. This isn't a weekend gig. It’s a long, grueling stretch of labor. When the chorus hits—the big, booming "Pay me! Pay me my money down!"—it’s not a request. It’s a demand. In the context of 2006, right after Hurricane Katrina, this song took on a whole new meaning. Bruce famously played the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival that year. When he played this song there, people weren't just dancing. They were screaming. They felt like the "Captain" (the government, the system) owed them big time.

The Live Evolution

If you ever saw the Seeger Sessions Tour, you know this was the peak of the show. It usually involved the entire band coming to the front of the stage.

Bruce would often turn it into a ten-minute jam. He’d point to different horn players for solos. He’d make the audience sing the chorus over and over until they were red in the face. It’s one of those rare songs that feels like it’s 100 years old and brand new at the same time.

Actually, even when he went back to the E Street Band, he occasionally pulled this one out. It’s a "break the glass in case of emergency" song. If a crowd is flagging or the energy is low, you drop the needle on this rhythm and everyone wakes up.

Why People Get It Wrong

A lot of folks think this is a Springsteen original. It’s not. Others think it’s just a "silly" song because it’s so upbeat.

📖 Related: The Real Story Behind I Can Do Bad All by Myself: From Stage to Screen

That’s a mistake.

Folk music often uses "happy" melodies to mask "sad" or "angry" stories. Think about it. If you’re a laborer who’s being exploited, singing a dirge makes you feel worse. Singing a loud, defiant, stomping anthem makes you feel powerful. It’s a survival tactic.

The song actually shares DNA with other Caribbean and Southern work songs. You can find versions of it titled "Pay Me" or "Every Time I Come to Town." The version Pete Seeger sang was a bit more polite. Springsteen’s version? It’s got some dirt under its fingernails. It’s got grit.

Comparing the Versions

| Artist | Vibe | Notable Feature |

|---|---|---|

| The Weavers | Clean, 1950s Folk | Harmonized vocals, very polite |

| Pete Seeger | Educational | Banjo-heavy, felt like a history lesson |

| Bruce Springsteen | Wild, Raucous | 18-piece band, New Orleans brass, high energy |

Basically, Bruce took a skeleton of a song and put a whole lot of meat on the bones. He understood that for a song like this to work in a modern arena, it needed to feel like a riot.

Impact on the Music Industry

When The Seeger Sessions came out, the industry didn't know what to do with it. It didn't fit on rock radio. It wasn't "country" enough for Nashville. But it ended up winning a Grammy for Best Traditional Folk Album.

More importantly, it introduced a whole generation of rock fans to the concept of the Great American Songbook—not the Sinatra stuff, but the real stuff. The songs written by people whose names are lost to time. Springsteen Pay Me My Money Down is the flagship of that movement. It proved that you could take a song from a Georgia dock and make it the highlight of a global tour.

You've got to appreciate the balls it took to do this. Imagine being at the height of your fame and saying, "Yeah, I'm going to put away the hits and play 19th-century boat songs." It shouldn't have worked. But it did.

Technical Elements of the Performance

If you're a musician trying to play this, the key isn't the chords. The chords are dead simple—it's mostly just a basic I-IV-V progression (think G, C, and D).

👉 See also: Love Island UK Who Is Still Together: The Reality of Romance After the Villa

The secret is the "shuffle." It’s that swinging rhythm. If you play it too straight, it sounds like a nursery rhyme. If you swing it too hard, it sounds like jazz. You have to find that sweet spot in the middle where it feels like a march.

The accordion is actually the "glue" of the Springsteen version. While the horns get the glory, Charlie Giordano’s accordion work keeps the folk roots intact. It gives it that European/Immigrant feel that matches the American South roots.

The Legacy of the Song

Today, you still hear this song at weddings, in bars, and at political rallies. It’s become a universal shorthand for "I’m tired of being screwed over."

It’s interesting how Springsteen’s career is often divided into "The E Street Era" and "The Other Stuff." But this song bridges the gap. It has the blue-collar heart of The River but the acoustic bones of Nebraska.

Honestly, if you want to understand the "working man" persona of Bruce Springsteen, don't look at "Born in the U.S.A." Look at this. "Born in the U.S.A." is a complex, misunderstood song about a Vietnam vet. Springsteen Pay Me My Money Down is a direct, unapologetic demand for what’s fair. No metaphors. No hidden meanings. Just pay me.

Actionable Takeaways for Listeners

If you’re just getting into this side of Bruce's work, here is how to actually appreciate it:

- Listen to the live version from Dublin. The Live in Dublin album captures the Seeger Sessions Band at their absolute peak. The energy on that recording of "Pay Me My Money Down" is significantly higher than the studio version.

- Look up the Georgia Sea Island Singers. If you want to hear where the soul of this song came from, check out the field recordings of Bessie Jones. It’ll give you a whole new perspective on the lyrics.

- Watch the "shouting matches." Find a video of the band performing this. Pay attention to how the horn players interact. It’s a lesson in musical telepathy.

- Use it for your own motivation. Seriously. If you’re having a bad day at work or feeling undervalued, crank this up in the car. It’s cathartic in a way very few songs are.

There's nothing "hidden" about this track. It’s loud, it’s proud, and it’s right in your face. It’s the sound of a man who realized that the best way to move forward was to look back at the songs that built the country in the first place.

Next time you hear those opening notes, don't just listen to the melody. Think about the docks. Think about the "forty nights at sea." And then, when the chorus comes, make sure you sing along loud enough to wake the neighbors. That’s what Bruce would want.

The real power of Springsteen Pay Me My Money Down lies in its refusal to be polite. It’s a song that demands a seat at the table. It’s messy, it’s loud, and it’s perfectly human. That’s why we’re still talking about it twenty years after the Seeger Sessions tour ended. It’s not just a cover; it’s a statement of purpose. You do the work, you get the pay. Simple as that.

Pro-tip for vinyl collectors: If you can find the original 2006 DualDisc or the later vinyl pressings of The Seeger Sessions, the mix is significantly more "open" than the digital versions. You can really hear the wood of the instruments and the room reverb, which makes the "Pay Me My Money Down" performance feel like it's happening right in your living room.