You’ve probably seen the one where a guy is sternly holding up his hand to a shot glass, looking like he’s about to lecture you on the virtues of tractor production. Or maybe the one where a giant bottle of vodka is literally strangling a factory worker. These aren't just weird relics from a failed social experiment. The soviet anti alcohol poster remains one of the most striking examples of how a government tries—and usually fails—to boss its citizens into being healthy. It’s high-octane propaganda mixed with genuine social desperation.

Honestly, the sheer volume of these posters is staggering. From the early days of the Bolsheviks right up until the collapse of the USSR in 1991, the state was locked in a constant, losing battle with the bottle.

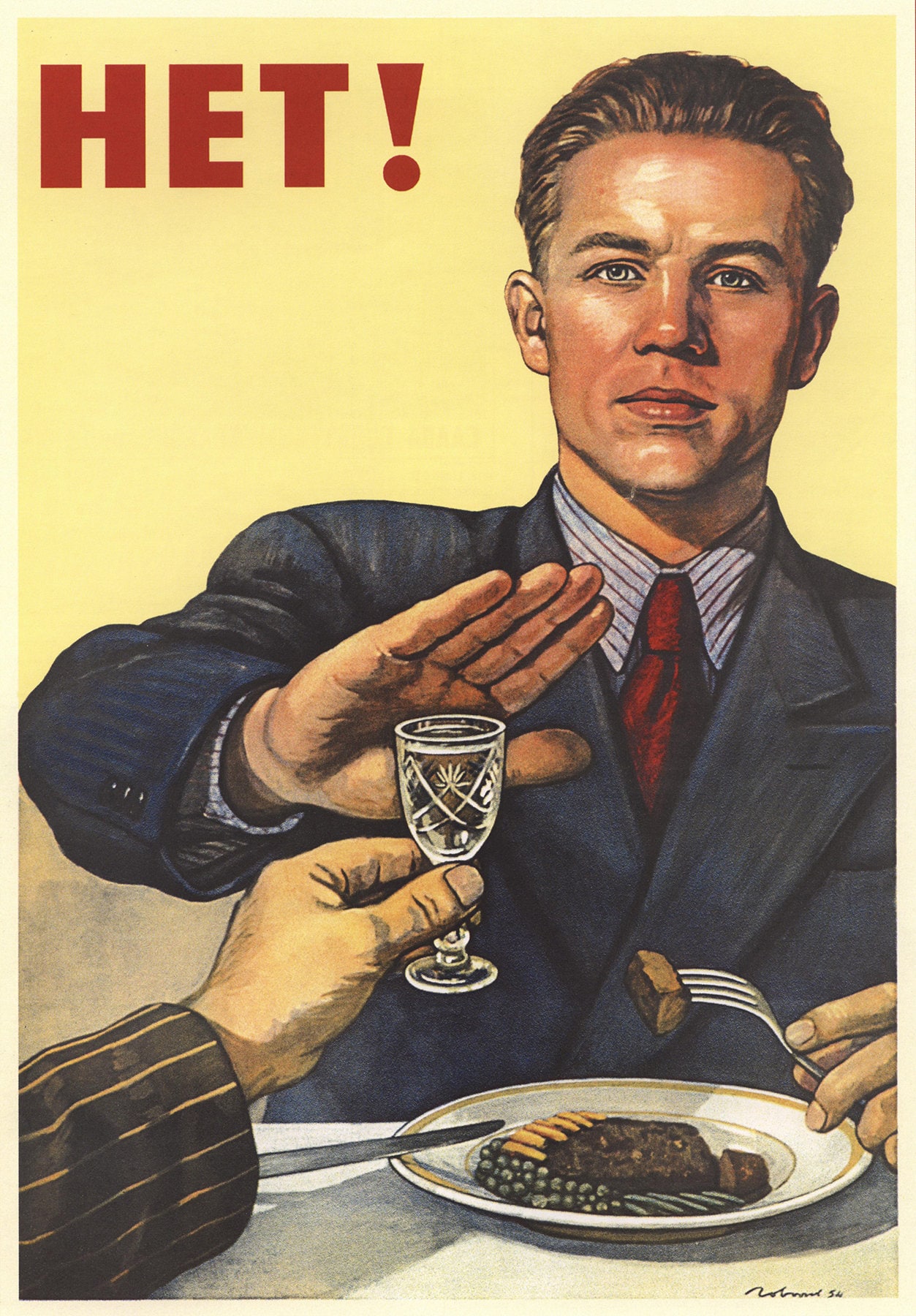

The "Nyet" Heard Round the World

The most famous soviet anti alcohol poster is undoubtedly Viktor Govorkov’s 1954 masterpiece titled simply, "Nyet!" (No!). It features a clean-cut man in a suit refusing a drink at a dinner table. It’s iconic. It’s a meme. But it’s also a lie. At the time, the Soviet Union was actually leaning heavily on vodka sales to balance the national budget. The state had a monopoly on alcohol. They needed the money, but they hated the consequences. This weird "double-think" is why the posters feel so aggressive; the state was basically yelling at people to stop doing the very thing that was funding the state.

Alcoholism wasn't just a health crisis in the USSR; it was a productivity killer. When you have a planned economy where every cog in the machine has to turn at the same speed, a hungover workforce ruins everything. Factories were falling behind. Accidents were everywhere. So, the artists were called in. They weren't just making "don't drink" ads; they were trying to redefine what it meant to be a "New Soviet Man."

The Aesthetics of Shame

The design language of these posters changed as the decades rolled by. In the 1920s, they were often Constructivist—sharp angles, bold reds, and experimental layouts. By the time of Stalin and Khrushchev, they moved into Socialist Realism. This meant the "good guys" (the sober ones) looked heroic, muscular, and bright-eyed. The "bad guys" (the drunks) were drawn as caricatures. They were often depicted with red noses, disheveled clothes, and sometimes even as pigs or monkeys.

It was a tactic of pure, unadulterated shame.

One particularly dark soviet anti alcohol poster from the 1970s shows a father drinking while his young daughter looks on in terror. The caption usually highlighted how the father was "drinking away" the child's future. It’s heavy-handed. It’s brutal. And according to most historians like Mark Schrad, author of Vodka Politics, it didn't really work. People just drank at home instead of in the pubs.

Gorbachev’s "Dry Law" and the Final Push

If you really want to understand the peak of the soviet anti alcohol poster, you have to look at 1985. Mikhail Gorbachev launched a massive anti-alcohol campaign shortly after taking power. He slashed vodka production and raised prices. He even famously plowed under ancient vineyards in Georgia and Moldova.

The posters from this era are some of the most creative and terrifying. You’ll see images of vodka bottles shaped like snakes, or a glass of spirits that reflects a skull. The art got more surreal. One famous image shows a man's head inside a bottle, his face distorted by the glass. The message was clear: alcohol is a prison.

But the campaign was a disaster.

The government lost billions in tax revenue. People started making "samogon" (moonshine) in their bathtubs using sugar, which led to a sugar shortage across the entire country. The posters were everywhere, but the vodka was in the black market. By 1988, the "Dry Law" was basically abandoned because the economy was cratering.

Why Do We Still Care?

There is something about the "look" of these posters that transcends the politics. Maybe it’s the bold typography. Maybe it’s the fact that they don't look like the polished, corporate "Drink Responsibly" ads we see today. They have a raw, desperate energy.

Collectors today pay thousands for original prints. Designers study them for their composition. You can buy "Nyet!" t-shirts on every corner of the internet. We’ve turned a tool of state repression into a kitschy lifestyle aesthetic.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Art

A common misconception is that these posters were the only way the state communicated. They weren't. They were part of a "visual environment." They were in schools, factories, train stations, and hospitals. You couldn't escape them. Imagine if every billboard you saw today wasn't trying to sell you a burger, but was instead yelling at you to stop eating sugar. That’s the level of saturation we’re talking about.

Another myth is that the artists were all forced to make these. In reality, many artists enjoyed the challenge of the anti-alcohol brief. It allowed for more caricature and "darker" imagery than the standard posters of happy peasants in wheat fields. You could experiment with shadows and grotesque features when you were drawing a drunk.

📖 Related: Saber tooth tiger kitten: Why they weren't the monsters we thought

How to Spot an Authentic Style

If you're looking to identify or collect a soviet anti alcohol poster, keep an eye on these specific visual markers:

- Color Palette: Dominated by red, black, and white. Red for the state/revolutionary spirit, black for the "evil" of alcohol.

- The "Hand" Motif: There is almost always a hand. A hand pushing away a glass, a hand grabbing a drunk by the collar, or a hand pointing accusingly at the viewer.

- Juxtaposition: The sober worker is usually looking toward the future (up and to the right), while the drunk is looking down or at the bottle.

- Typography: The font is usually sans-serif, bold, and loud. It’s designed to be read from across a factory floor.

The irony is that while the Soviet Union is gone, the problem they were fighting hasn't really changed. Modern Russia still deals with massive rates of alcohol-related issues, but the posters are gone, replaced by standard commercial regulations. The posters remain as ghosts of a time when the state thought it could paint its way to a sober utopia.

Actionable Steps for Enthusiasts and Collectors

If you're fascinated by this era and want to dig deeper or start a collection, here is how you actually do it without getting ripped off.

1. Verification of Provenance

Don't just buy a "vintage" poster on a whim. Many "original" posters sold on auction sites are actually high-quality reprints from the 1990s. Look for the printer's mark (usually in tiny text at the bottom). It should list the city of publication (usually Moscow or Leningrad), the "тираж" (print run size), and the price in kopecks. If these details are missing or look "too clean," it's likely a modern reproduction.

2. Focus on the Artist

Search specifically for works by Viktor Govorkov, Irakli Toidze, or the Kukryniksy collective. These were the heavy hitters. Posters by known artists hold their value much better than anonymous state-produced graphics. Govorkov, in particular, is the gold standard for the 1950s style.

3. Digital Archives for Research

Before spending money, browse the digital collections of the Russian State Library or the Ne Boltai! collection. This will give you a sense of what the paper quality and color saturation should actually look like. You can also see how themes evolved from the "Stakhanovite" 1930s to the more cynical 1980s.

4. Framing for Preservation

If you do score an original, do not use cheap frames. Soviet poster paper was often low-quality "newspaper" grade and is highly acidic. Use UV-protective glass and acid-free matting. If you don't, the red ink—which is notorious for fading—will turn a dull pink within a few years of being exposed to sunlight.

5. Historical Context Reading

To truly appreciate the art, read A History of Vodka by William Pokhlebkin. It’s a bit controversial in academic circles, but it provides the cultural backdrop that explains why the state was so obsessed with these posters in the first place. Understanding the "Vodka Monopoly" makes the posters look less like health advice and more like a desperate attempt at damage control.

The soviet anti alcohol poster isn't just art; it's a paper trail of a government trying to solve a deep-seated cultural habit with ink and paper. It didn't work, but it sure left behind some of the most compelling graphic design of the 20th century.