You know that feeling when a song starts and you’re instantly five years old again, sitting in the back of a wood-paneled station wagon? Or maybe you’re twenty, staring at a rainy window in a dorm room? That’s the Cat Stevens effect. His music doesn't just play; it lingers. It sticks to the ribs of your soul.

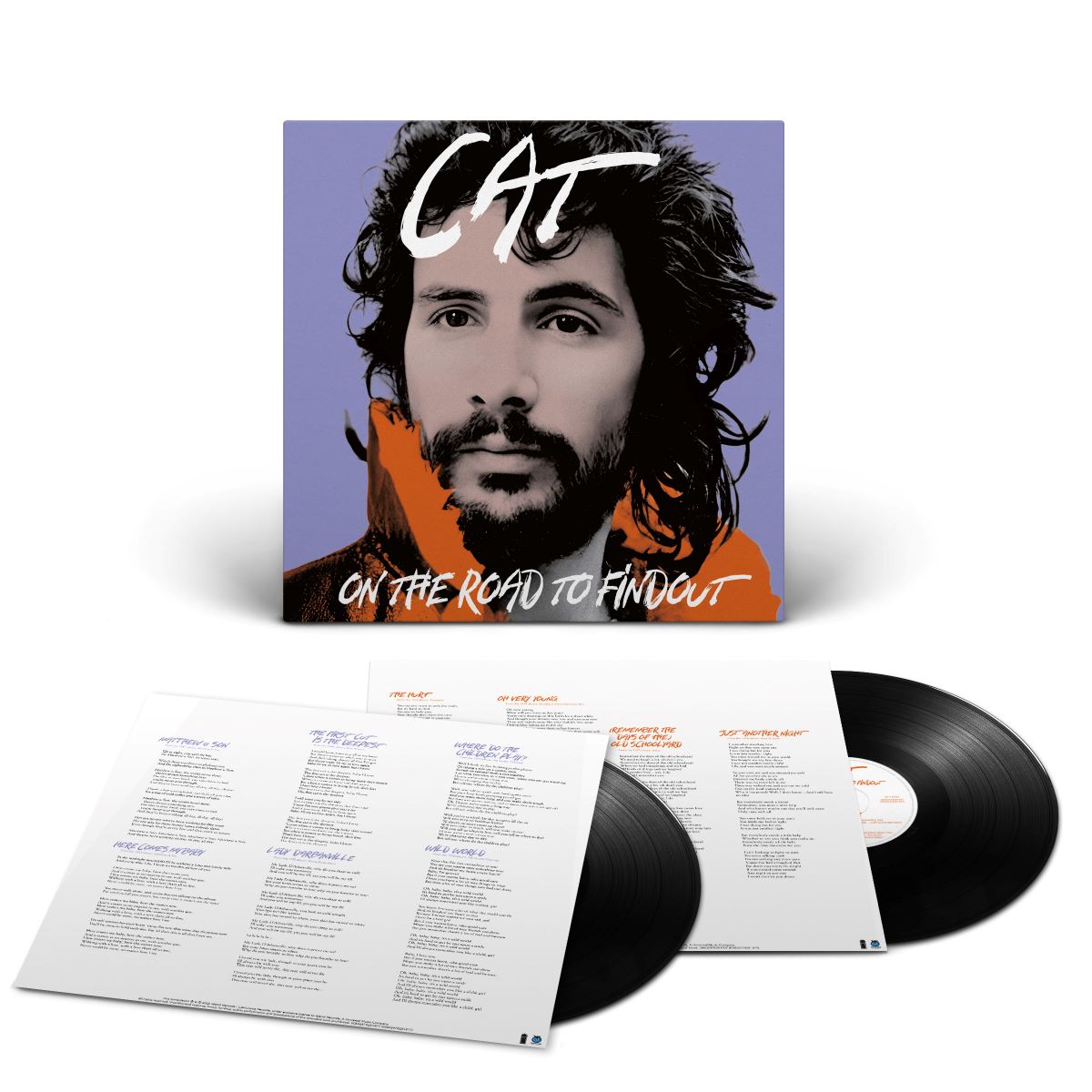

When people talk about songs Cat Stevens greatest hits, they're usually referring to that iconic 1975 compilation with the orange cover and the drawing of a tiger. It sold millions. Honestly, it’s one of those rare "perfect" albums. Every track feels like it was hand-picked by fate. But there’s a lot more to these songs than just catchy folk-pop melodies.

The tracks that defined an era

Let's get real for a second. Most "greatest hits" albums are just corporate cash grabs. They throw together some radio edits and call it a day. But this collection? It’s different. It captures a specific moment in the 70s when the world was pivotally shifting from hippie optimism to a deeper, more grounded introspection.

"Wild World" is the big one. Everyone knows it. It’s been covered by everyone from Mr. Big to Maxi Priest. But have you actually listened to the lyrics lately? It’s remarkably complex. It’s a breakup song, sure, but it’s wrapped in this weirdly fatherly advice. It’s Stevens saying, "I’m sad you’re leaving, but also, watch out because the world is literally going to eat you alive."

Then you’ve got "Father and Son." This song is a masterclass in perspective. Stevens sings both parts—the deep, resonant voice of the father and the higher, more urgent tone of the son. It’s about the generation gap, but it feels timeless because that argument never actually ends. Every son eventually becomes the father, and every father remembers being the son who wanted to just... go.

💡 You might also like: Why Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy Actors Still Define the Modern Spy Thriller

Why "Morning Has Broken" wasn't even his

A lot of people think Cat Stevens wrote "Morning Has Broken." He didn't.

It’s actually a Christian hymn from the 1930s. The lyrics were written by Eleanor Farjeon, and the tune is an old Gaelic melody called "Bunessan." Stevens took this churchy, traditional piece and turned it into a global pop smash. Rick Wakeman—the legendary keyboardist from Yes—played that iconic piano opening. He reportedly got paid about £10 for the session. Imagine being the guy who played one of the most famous piano riffs in history for the price of a couple of pizzas.

The secret sauce of the 1975 compilation

Why does this specific batch of songs work so well?

- The pacing: It moves from the upbeat "Peace Train" to the contemplative "Moonshadow" without missing a beat.

- The production: Paul Samwell-Smith (formerly of The Yardbirds) produced most of these. He kept things sparse. It’s mostly just acoustic guitar, some light percussion, and that incredible, gravelly-but-sweet voice.

- The vulnerability: Unlike a lot of 70s rock stars who were busy being "cool," Stevens was busy being "honest." He sang about being scared, being hopeful, and seeking something bigger than himself.

"Moonshadow" is a perfect example of his philosophy. It’s a song about losing everything—your hands, your eyes, your legs—and still finding a reason to be happy. It sounds like a nursery rhyme, but it’s actually kind of dark if you think about it. It’s basically "toxic positivity" before that was a buzzword, but done with so much genuine charm you can't help but smile.

📖 Related: The Entire History of You: What Most People Get Wrong About the Grain

Beyond the orange album

While the 1975 songs Cat Stevens greatest hits list is the "Gold Standard," he had a whole life before and after it.

Before he was the folk troubadour, he was a 60s pop star. He wrote "The First Cut Is the Deepest," which became a massive hit for P.P. Arnold, then Rod Stewart, then Sheryl Crow. The guy was a songwriting factory.

Then, at the height of his fame, he almost drowned in the Pacific Ocean. That’s the story, anyway. He promised God that if he survived, he’d work for Him. Shortly after, he converted to Islam, changed his name to Yusuf Islam, and walked away from the music industry for nearly 30 years. He even auctioned off all his guitars for charity.

For decades, these "greatest hits" were the only way fans could connect with him. He wasn't touring. He wasn't making new secular music. Those eleven or twelve tracks became a sacred text for a generation of listeners.

👉 See also: Shamea Morton and the Real Housewives of Atlanta: What Really Happened to Her Peach

The 2026 perspective

Now that we’re in 2026, his music has taken on a new layer of meaning. In a world of AI-generated beats and 15-second TikTok hooks, the raw, analog soul of "Peace Train" feels like a cool glass of water in a desert.

People are still discovering these songs because they deal with "The Big Stuff." Death. God. Growing up. Letting go. You can’t automate that kind of emotional resonance.

How to actually listen to Cat Stevens today

If you’re looking to dive back in, don't just stream a random "This is Cat Stevens" playlist. Do it right.

- Find the original 1975 vinyl. The mastering on the old A&M or Island pressings is much warmer than the digital versions.

- Listen to "Harold and Maude." Many of his best songs, like "If You Want to Sing Out, Sing Out," weren't on the original greatest hits but are essential to his legacy.

- Check out the 50th-anniversary remasters. Yusuf has been very involved in rereleasing his old catalog lately, and the sound quality is often stunning.

The reality is that songs Cat Stevens greatest hits will likely still be on people's "must-listen" lists in another fifty years. They aren't just songs; they’re little pieces of a man’s search for meaning. And as long as humans are still searching for meaning, we’re going to need a soundtrack for the journey.

To get the most out of this music now, try listening to Tea for the Tillerman and Teaser and the Firecat in their entirety. These two albums provide the backbone for almost every "greatest hits" collection and offer a much deeper look into the storytelling that made Stevens a legend. Focus on the lyrics of "Where Do the Children Play?"—it’s a song about environmentalism and technology written in 1970 that feels like it could have been written this morning.