He sits on a stool. He tunes the guitar—a custom Olson that costs more than most used cars—and he smiles that crooked, familiar smile. If you’ve ever been to a James Taylor concert, you know the vibe. It isn't just a performance; it’s a collective exhale. People don't just listen to songs by James Taylor; they inhabit them.

Honestly, it’s kinda weird how much we still need him. In a world of hyper-processed pop and TikTok sounds that last twelve seconds, Taylor’s music is an anomaly. It’s slow. It’s methodical. It’s deeply, almost uncomfortably, personal. We’re talking about a guy who turned his stay in a psychiatric hospital into a Top 10 hit. That takes guts, or at least a level of honesty we rarely see anymore.

The unexpected grit behind "Fire and Rain"

Everyone thinks they know "Fire and Rain." It’s the ultimate campfire sing-along, right? Wrong. Well, okay, people do sing it at campfires, but the backstory is heavy. Like, really heavy. Most people assume the line "sweet dreams and flying machines in pieces on the ground" refers to a plane crash. It doesn't.

The "Flying Machine" was actually the name of his short-lived band in the late sixties. The song is a three-part grieving process. One verse is about his friend Suzanne Schnerr, who died by suicide while James was away recording in London. His friends actually kept the news from him for months because they didn't want to mess up his big break with Apple Records. Imagine that. You’re recording with Paul McCartney and George Harrison, and meanwhile, back home, one of your closest friends is gone.

The other verses? They're about his own struggle with heroin addiction and the exhaustion of trying to make it in the music industry. It isn't a "pretty" song once you look at the bones of it. It’s a desperate prayer. Taylor has admitted in interviews, specifically with Rolling Stone, that he’s surprised he can still sing it with conviction after all these years. But he does. Every single night.

Why his guitar style is basically impossible to copy

If you ask a hobbyist guitarist to play some James Taylor, they’ll usually give you a basic fingerpicking pattern. But they're usually doing it wrong. Taylor’s style is a weird, beautiful hybrid. He uses his fingernails—which he reinforces with fiberglass and resin—to get this bright, percussive snap.

The "Nails" factor

He literally glues his nails. If he breaks one, the show is basically over. He’s mentioned this to luthier James Olson, the man who builds his guitars. The technique involves his thumb playing the bass line while his first three fingers handle the melody, but he adds these little "hammer-ons" and "pull-offs" that make the guitar sound like a piano.

👉 See also: America's Got Talent Transformation: Why the Show Looks So Different in 2026

It’s complex. It’s "Carole King on six strings." That’s how he describes it. He was trying to emulate her piano playing on his acoustic guitar. If you listen to the way the chords move in "Don't Let Me Be Lonely Tonight," you’ll hear these jazzy, sophisticated transitions that shouldn't work in a folk song. But they do.

The Apple Records era and the Beatles connection

People forget that James Taylor was the first non-British act signed to the Beatles' Apple Records. That is a massive deal. Peter Asher (of Peter and Gordon fame) heard James's demo and basically lost his mind. He took it to Paul McCartney. Paul liked it. George Harrison liked it so much he actually "borrowed" the title of James’s song "Something in the Way She Moves" for a little track he was writing called "Something."

- James Taylor's debut album featured McCartney on bass.

- The recording sessions were chaotic because of the Beatles' own internal drama.

- James was struggling with addiction during the sessions, leading to a temporary return to the States for treatment.

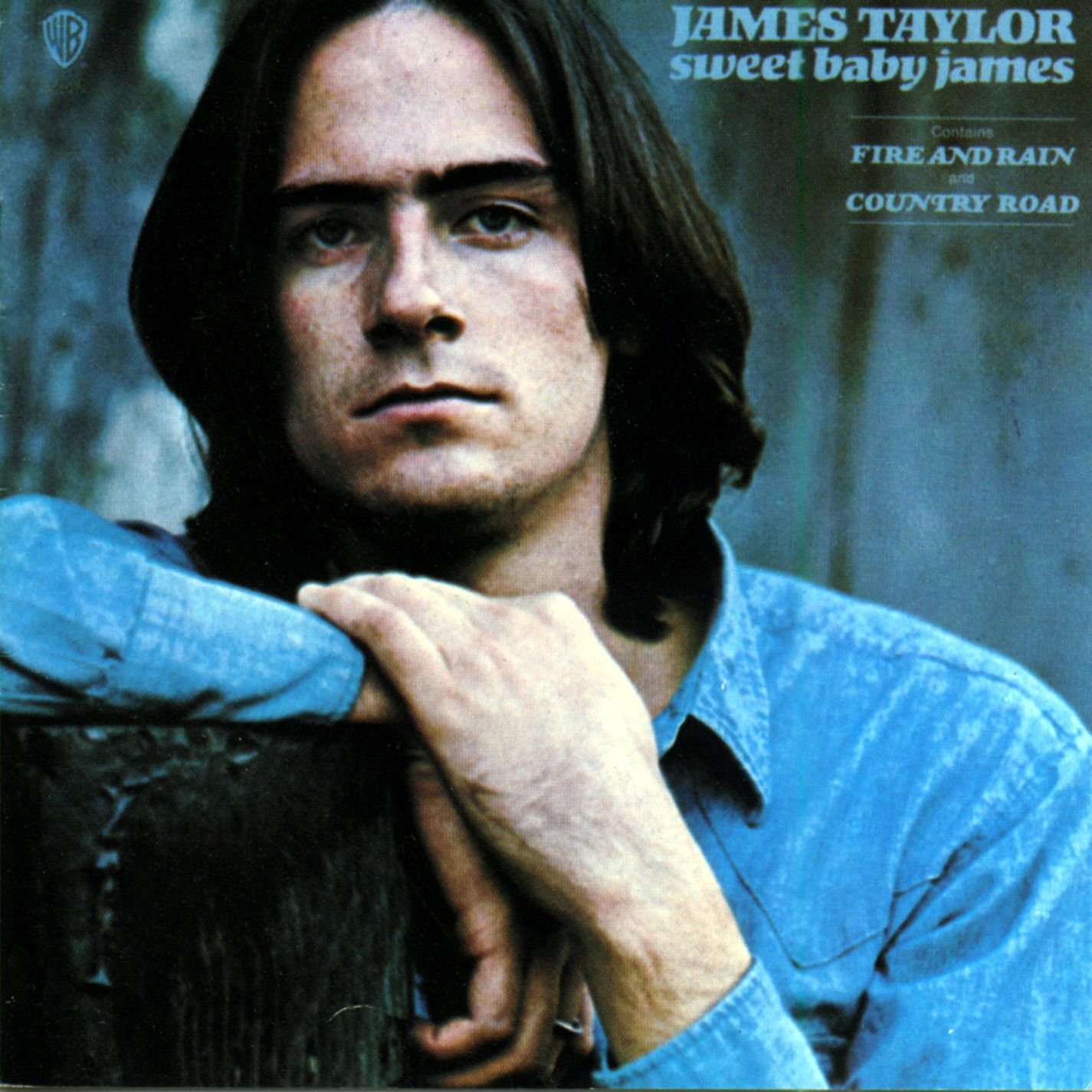

It wasn't an immediate success. The album kind of flopped initially. It took him moving to Warner Bros. and releasing Sweet Baby James in 1970 for the world to catch up. But that Beatles DNA is all over his early work. The melodic sense, the crisp production—it’s all there.

Misconceptions about the "Mellow" label

Critics in the late 70s were sometimes mean to James. They called him the "Lullaby King" or "Soft Rock's Poster Boy." It was meant as a dig. They thought he was too safe.

But listen to "Steamroller." It’s a parody of white-boy blues, sure, but he plays it with this snarling, aggressive edge that proves he’s not just a guy in a rocking chair. Or "Copperline," a song he co-wrote with Reynolds Price. It’s a haunting, literary look at the disappearance of the rural South. There’s a lot of shadow in these songs. You just have to be willing to look past the soothing voice to see the ghosts.

The "You've Got a Friend" debate

Technically, he didn't write it. Carole King did. She wrote it in response to a line in Taylor's "Fire and Rain" ("I've seen lonely times when I could not find a friend"). He played it, she told him he should record it, and it became his only number-one hit. Some purists argue it’s not a "true" James Taylor song because he didn't pen the lyrics. But honestly? He owns it. His version is the definitive one because his voice carries that specific type of weary comfort that Carole’s (brilliant) version doesn't quite lean into.

✨ Don't miss: All I Watch for Christmas: What You’re Missing About the TBS Holiday Tradition

The impact of recovery on his songwriting

There is a distinct "Before" and "After" in Taylor’s catalog. The early stuff is raw, wounded, and often erratic. Then you have the post-1985 era. After he got sober, his writing changed. It became more observational, more grateful.

"Walking Man" is a great example of his mid-career depth. It’s about his father, Isaac Taylor, who was a dean at the University of North Carolina. His dad was a bit of a mystery—a man who would go for long walks and disappear into himself. James captures that distance perfectly. He isn't angry anymore; he’s just trying to understand. This shift from "me-centric" songs to "human-centric" songs is why he’s survived while other singer-songwriters from the 70s faded away.

The technical genius of "Your Smiling Face"

Two minutes and forty-five seconds of pure pop perfection. That’s it. But if you analyze the key changes? It’s a nightmare for a vocalist. The song keeps modulating up. It starts in E, jumps to F#, then G, then A. By the end, he’s singing in a register that most men can only reach if they've stepped on a Lego.

He makes it sound easy. That’s the James Taylor trick. He takes incredibly difficult musical theory—complex modulations, diminished chords, syncopated fingerstyle—and presents it as if he’s just humming to himself in the kitchen.

What we get wrong about his "Simple" life

People think of him as this quintessential New Englander, living a quiet life in the Berkshires. And yeah, he does. But his history is messy. He was married to Carly Simon in what was essentially the "royal wedding" of the 70s rock scene. It was volatile. It was fueled by fame and substance abuse.

When they divorced, it was brutal. He didn't speak about it much. He didn't write "scathing" breakup albums in the way we expect now. Instead, he wrote songs like "Her Town Too," which captures the awkward, painful reality of a shared social circle after a split. It’s subtle. It’s grown-up. It’s a lot more interesting than a diss track.

🔗 Read more: Al Pacino Angels in America: Why His Roy Cohn Still Terrifies Us

How to actually listen to James Taylor in 2026

If you’re just getting into him, don't just stick to the Greatest Hits (though that album has been on the Billboard charts for basically a century). Dig into the deep cuts.

- "Looking for Love on Broadway": A funky, surprisingly groovy track from In the Pocket.

- "Millworker": Written for the musical Working, based on Studs Terkel's book. It’s a devastating look at the life of a female factory worker. It proves he can write from perspectives other than his own.

- "Shed a Little Light": A tribute to Martin Luther King Jr. that showcases his gospel influences.

Songs by James Taylor aren't just background music for dentists' offices. They are masterclasses in American songwriting. He took the folk traditions of the 60s, mixed them with the sophisticated pop of the 70s, and somehow stayed relevant through the synth-heavy 80s and the grunge 90s.

Actionable insights for fans and musicians

To truly appreciate the craft, stop listening to the Spotify "This Is James Taylor" playlist on shuffle while you do the dishes. Do this instead:

- Listen on high-quality headphones: His production, especially on the Hourglass album, is legendary. He won a Grammy for Best Engineered Album for a reason. You can hear the wood of the guitar and the breath between the notes.

- Watch the 1970 BBC In Concert special: It’s on YouTube. It’s just him, a guitar, and a very small audience. You’ll see the fingerpicking technique up close and realize how much of the sound is in his hands, not the gear.

- Analyze the lyrics as poetry: Take a song like "October Road" or "Mean Old Man." Read the lyrics without the music. The rhyme schemes are often internal and unexpected, avoiding the "moon/june" cliches of his contemporaries.

- Visit the Berkshires: If you’re ever in Massachusetts, go to Tanglewood. Seeing him play there is a rite of passage. It’s his home turf, and the atmosphere changes the way the music hits you.

The reality is that Taylor’s music works because it’s vulnerable. In an era where everyone is trying to look "cool" or "unbothered," he’s okay with looking hurt. He’s okay with being sentimental. He’s okay with being a "handyman" for the soul. That kind of authenticity doesn't have an expiration date.

Next time you put on "Carolina in My Mind," listen for the way he describes the "dark and silent late last night." He isn't just describing a time of day. He’s describing a state of mind. That’s the genius of it. He’s been there, he survived it, and he’s singing us back home.

Check out the American Standard album if you want to hear how he reimagines the Great American Songbook through his specific guitar lens. It’s a great way to see how his style adapts to music he didn't even write.