Ken Kesey was a giant. Not just physically, though he was a wrestler with a neck like a tree trunk, but culturally. Most people know him for One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, thanks in large part to Jack Nicholson’s grin. But for those who actually live in the rainy, moss-covered corners of the Pacific Northwest—or anyone who has ever felt the crushing weight of family expectations—his second novel is the real masterpiece. Published in 1964, Sometimes a Great Notion is a sprawling, difficult, and beautiful mess of a book. It’s famous for many things, but nothing sticks in the ribs quite like the Stamper family motto: Never Give an Inch.

It’s more than a slogan. It’s a philosophy that borders on a pathology.

When you look at that phrase carved into a plaque or painted on a sign in the book, it feels heroic. It’s the rugged individualism that built the West, right? Well, sort of. Kesey was smart enough to show that "Never Give an Inch" is both the thing that keeps the Stampers alive and the thing that eventually destroys their souls. It’s a double-edged sword that’s still sharp sixty years later.

The Oregon Rain and the Stamper Spirit

The setting isn't just a backdrop; the Oregon coast is a character that’s trying to kill everyone. In the fictional town of Wakonda, the rain never really stops. It turns the ground to soup and the river into a hungry beast. This is where the Stampers run a gyppo logging operation. They are independents. They don't like unions, they don't like the town, and they barely like each other.

The patriarch, Henry Stamper, is the one who etched Sometimes a Great Notion never give an inch into the family’s DNA. He’s an old-school pioneer type who views the world as a constant battle of wills. If you yield a single inch to the river, it takes the house. If you yield an inch to the union, they take your livelihood. If you yield an inch to your own emotions, you’re finished.

Henry’s son, Hank, is the modern embodiment of this. He’s a powerhouse. He’s the guy who stays out on the logs when the cables are snapping and the mud is sliding. He’s the one who decides to keep logging even when the rest of the town is on strike, turning the Stampers into local pariahs. He doesn't do it because he hates the strikers—not exactly—but because his father’s voice is always in his head.

Never give an inch. It’s a brutal way to live. It requires a level of physical and mental toughness that most of us can’t even imagine. But Kesey shows us the cost. By refusing to bend, the Stampers become brittle. They can’t empathize. They can’t adapt to a changing world. They just keep pushing back against the tide until the tide finally wins.

A Tale of Two Brothers

The real meat of the story isn't the logging strike. It’s the return of Leland Stamper, the younger, intellectual brother who ran away to the East Coast to get an education and escape the family shadow. Lee is the opposite of Hank. He’s thin, sensitive, and carries a massive grudge. He comes back to Wakonda ostensibly to help with the logging, but really, he’s there for revenge.

This is where the Sometimes a Great Notion never give an inch mantra gets complicated. Lee wants to make Hank "give an inch." He wants to find the crack in his brother’s armor.

👉 See also: Ted Nugent State of Shock: Why This 1979 Album Divides Fans Today

The book uses a revolutionary narrative style. Kesey jumps between perspectives, sometimes in the middle of a paragraph. You’ll be inside Hank’s head, feeling the grit of the sawdust, and then suddenly you’re in Lee’s head, feeling his childhood trauma. It’s disorienting at first. It feels like the chaotic flow of the river itself. But it forces you to see that "Never Give an Inch" looks different depending on who is saying it. To Hank, it’s about survival and honor. To Lee, it’s a wall he has to climb over or tear down.

The Most Famous Scene in Oregon Literature

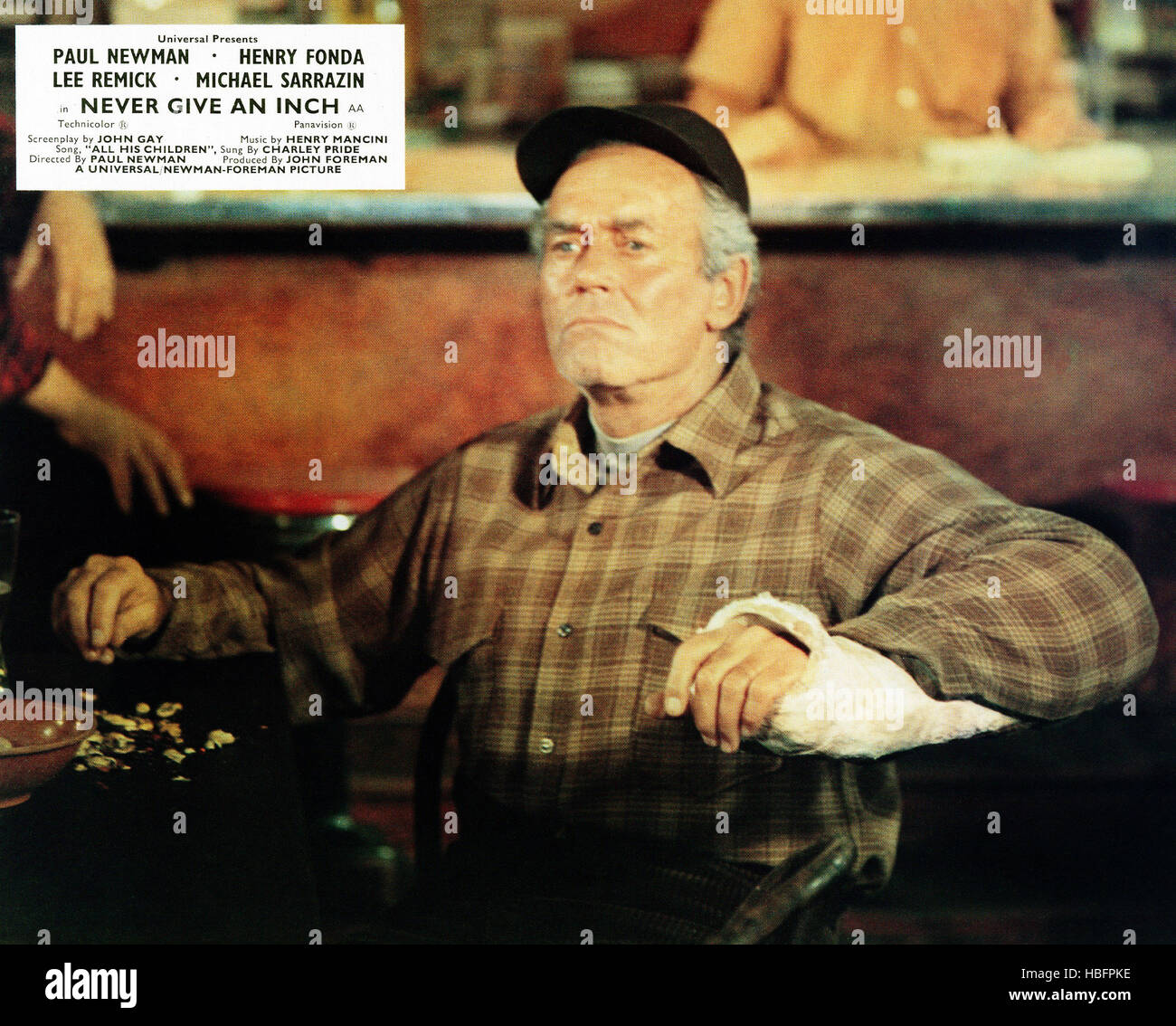

You can't talk about this book or the 1971 film directed by Paul Newman without talking about the river scene. If you’ve seen it, you know. If you haven't, it’s one of the most harrowing sequences in cinema history.

During a logging accident, Joe Ben Stamper—the most likable, optimistic member of the clan—gets pinned under a massive log in the rising tide. Hank is there, trying desperately to lift the log with a jack. But the water is coming up. Joe Ben is cracking jokes at first, trying to keep the mood light, but the water gets to his chin.

Hank refuses to give up. He’s living the motto. He won't give an inch to the river. But in a cruel twist of fate, as Joe Ben starts to panic, he begins to laugh hysterically, and he inhales the water. He drowns because of a moment of frantic, bubbly joy in the face of death.

It’s a gut punch. It’s the moment where the philosophy of "Never Give an Inch" faces its ultimate test. Hank stays. He keeps fighting. Even when the town is mocking him, even when his family is falling apart, he goes back to work. Some call it bravery; some call it a mental illness. Kesey lets you decide.

Why the Title Matters

The title comes from the Lead Belly song "Goodnight, Irene." The lyrics go:

Sometimes I live in the country / Sometimes I live in town / Sometimes I have a great notion / To jump into the river and drown.

That "great notion" is the temptation to just give up. To let the river win. To stop fighting the rain, the unions, and the internal demons. The Stamper motto is the literal shield against that "great notion." To never give an inch is to refuse the easy exit. It’s a commitment to the struggle, even if the struggle is meaningless.

✨ Don't miss: Mike Judge Presents: Tales from the Tour Bus Explained (Simply)

Honestly, it’s a very existentialist American idea. It’s Sisyphus pushing the rock, but the rock is a Douglas fir and Sisyphus is wearing cork boots and a flannel shirt.

The 1971 Film vs. The Novel

Paul Newman’s movie is actually pretty good, which is rare for a book this dense. Newman played Hank, and Henry Fonda played the old man. They captured the grit perfectly. However, the movie had to trim a lot of the psychological depth. In the book, the internal monologue of the characters is what makes the Sometimes a Great Notion never give an inch theme so resonant.

In the film, it feels more like a standard "tough guy" Western set in the woods. In the book, it’s a Greek tragedy. If you really want to understand the "Never Give an Inch" mindset, you have to read the prose. Kesey’s writing is muscular. It smells like diesel and wet cedar. He doesn't just tell you they are tough; he makes the sentences feel tough.

Is "Never Give an Inch" Still Relevant?

We live in a world that’s all about "pivot" and "flexibility." We’re told to be agile. The idea of "Never Give an Inch" feels like an antique from a dumber, more stubborn era.

But there’s something about it that still pulls at the American heart. We admire people who stand their ground. Whether it’s a political movement, a small business owner refusing to sell out, or an artist sticking to their vision, that stubbornness is a core part of the national identity.

The problem is the "Great Notion."

When does standing your ground turn into a suicide pact? When does "Never Give an Inch" mean you lose your wife, your brother, and your peace of mind? Kesey doesn't give us a clean answer. At the end of the book, the Stampers are still there, still logging, still fighting. They haven't "won" in any traditional sense. They’ve just survived.

Practical Takeaways from the Stamper Philosophy

If you’re looking to apply some of this grit to your own life without drowning in a river, here’s how to parse the Stamper way:

🔗 Read more: Big Brother 27 Morgan: What Really Happened Behind the Scenes

1. Know Your River

You have to know what you’re fighting. For the Stampers, it was nature and the town. For you, it might be a career hurdle or a personal habit. You can’t refuse to give an inch if you don't know where the line is drawn.

2. Recognize the Cost

The Stampers lost almost everything to keep their pride. Before you adopt a "never yield" attitude, look at the price tag. Is the "inch" you’re holding onto worth the relationships you might lose? Sometimes it is. Often, it isn't.

3. Resilience vs. Rigidity

There is a fine line between being resilient (bouncing back) and being rigid (breaking). The Stampers were rigid. They didn't bounce; they just stood there until they snapped. True strength usually requires a little bit of "give" so you can reposition for the next hit.

4. The Value of the Struggle

The most "human" part of the book is the realization that the struggle itself gives life meaning. Even if the world is going to end and the river is going to take the house, there is a certain dignity in waking up, putting on your boots, and heading into the woods.

Final Thoughts on the Stamper Legacy

Ken Kesey wrote this book before the Sixties really exploded, before he became the leader of the Merry Pranksters and started riding around in a bus called "Further" while high on LSD. It’s a bridge between the old, rugged America and the new, psychedelic America.

Sometimes a Great Notion never give an inch is a reminder that humans are stubborn, beautiful, and occasionally very stupid creatures. We will fight for things that don't matter just because we said we would. We will hold onto a sinking log because our father told us to.

If you haven't read it, find a copy. It’s long. It’s hard to get through the first 100 pages. But once you’re in the current of Kesey’s prose, you won't want to get out. You’ll find yourself rooting for these flawed, angry, stubborn men. You’ll feel the rain on your neck. And you might just find yourself standing a little taller the next time the world tries to push you around.

To truly understand the Stamper mindset, your next step is to watch the 1971 film for the visual context, then dive into the novel's first chapter—specifically focusing on the description of the house's location on the bend of the river. This physical placement is the ultimate metaphor for the entire family's existence. Pay close attention to how the river eats at the bank, and how the Stampers have spent decades reinforcing that single, solitary inch of dirt. After that, look into the real-life history of Oregon's independent "gyppo" loggers to see how Kesey captured a vanishing breed of American worker.