Woody Guthrie wasn't trying to write a radio hit. He was just trying to survive the Dust Bowl. When you sit down and actually read the so long it's been good to know you lyrics, you aren't just looking at a folk song. You're looking at a survival manual written in the middle of a literal apocalypse. It’s a song about the end of the world—or at least, the end of the world as those people knew it in the 1930s.

Funny enough, most people today recognize the chorus as a cheerful goodbye. You hear it at summer camps. You hear it at the end of parties. But the actual verses? They are terrifying. They describe a sky turning black and people losing their minds.

The Dust Bowl Reality Behind the Song

Guthrie wrote the original version of this track in 1935. He was in Pampa, Texas. If you've never looked at photos of the "Black Sunday" dust storm of April 14, 1935, you should. It looked like a mountain of black oil rolling across the plains. People thought it was the Day of Judgment.

The lyrics reflect that specific, bone-deep fear.

Guthrie talks about a "dusty old dust" that settled over everything. It wasn't just dirt; it was the destruction of their livelihoods. One of the most haunting verses mentions a church congregation. When the dust hits, the people inside don't just pray—they start confessing their sins because they are convinced they are about to die. That isn't a metaphor. It was documented by historians like Donald Worster in his book Dust Bowl: The Southern Plains in the 1930s.

The song captures a very specific type of American trauma. It’s the moment when the land you love turns against you.

Why the Lyrics Kept Changing

Most people don't realize there are actually several versions of the so long it's been good to know you lyrics. This is where things get interesting for music nerds.

Guthrie was a rambler. He changed his songs depending on who was listening. The version he recorded for the Library of Congress (working with Alan Lomax) is raw and focused on the disaster. But later, especially during the 1940s and 50s, the song got "cleaned up" for a national audience.

The Weavers, a massive folk group featuring Pete Seeger, took the song and turned it into a chart-topping pop hit in 1951. They softened it. They made it more about a guy leaving a girl or a traveler saying goodbye to a town. They took out the "Black Sunday" grit and replaced it with a more universal, slightly melancholy sentiment. Honestly, that’s why we still sing it today. If it had stayed a song strictly about a 1935 weather event, it might have faded into the archives.

But Guthrie’s original intent was much darker.

He used the phrase "So long, it's been good to know you" as a sarcastic, almost nihilistic shrug. It was what you said when you realized your farm was gone, your lungs were full of silt, and you had to get on the road to California or starve.

✨ Don't miss: Austin & Ally Maddie Ziegler Episode: What Really Happened in Homework & Hidden Talents

Breaking Down the Key Verses

Let’s look at the "confession" verse because it’s arguably the most powerful part of the original composition.

A dust storm hit, an' it hit like thunder;

It dusted us over, an' it covered us under;

En' it blocked out the traffic an' blocked out the sun,

Straight for home all the people did run.

That "hit like thunder" line isn't poetic fluff. Static electricity in those storms was so high that it would short out car engines and create blue sparks on barbed-wire fences.

Then comes the part about the church. Guthrie writes about the "deacon" and the "elder" getting down on their knees. They think the end is here. In the context of the Great Depression, this was a massive shift in the American psyche. The song captures the transition from being a settled farmer to being a "homeless" migrant.

It’s about the loss of identity.

The Evolution of the Chorus

The chorus is what sticks in your head.

"So long, it’s been good to know you."

It’s simple. It’s catchy. But why does it work so well? Musically, it’s a waltz. It has that 3/4 time signature that makes you want to sway. It feels like a campfire song. But the repetition of "long time since I’ve been home" reminds you that the singer is a displaced person.

You’ve probably heard variations of this. Some people sing "I've got to be drifting along." Others focus on the "dusty old dust."

There’s also a later version Guthrie wrote that includes references to the war and political activism. Woody was never one to stay in one place, lyrically or physically. He saw his music as a tool for social change, not just entertainment. By the time he was living in New York and hanging out with the Almanac Singers, the song had become an anthem for the working class.

🔗 Read more: Kiss My Eyes and Lay Me to Sleep: The Dark Folklore of a Viral Lullaby

Why This Song Still Ranks Today

You might wonder why people are still searching for these lyrics in 2026.

It’s because the "Dust Bowl" isn't just a history lesson anymore. With modern concerns about climate change and environmental collapse, Guthrie’s words feel weirdly prophetic again. When people see images of massive wildfires or orange skies over New York City, they reach for the music that described the last time the sky fell.

The so long it's been good to know you lyrics tap into a fundamental human experience: saying goodbye to a life you thought was permanent.

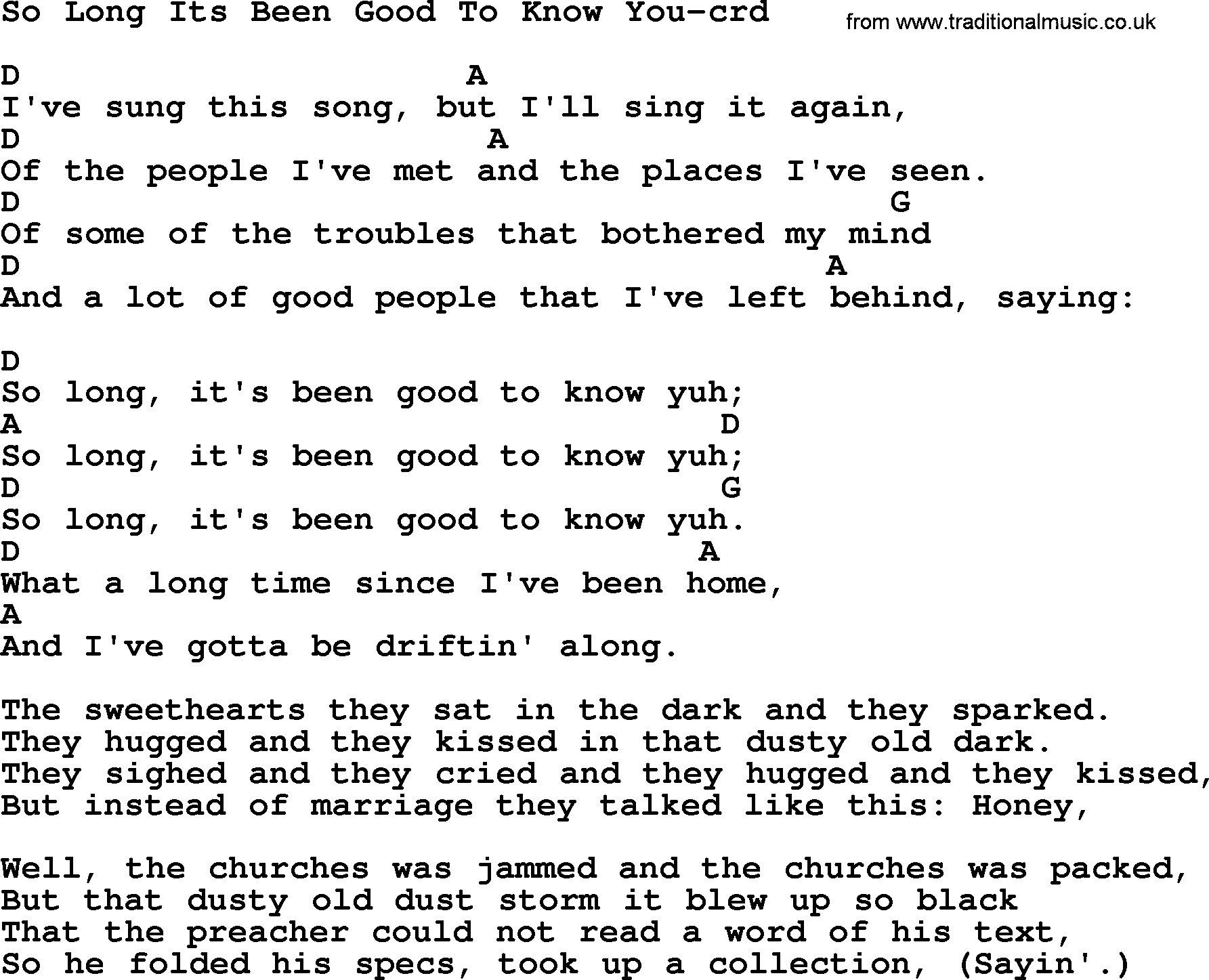

It’s also a staple in the American songbook. If you are learning the guitar, this is one of the first songs you learn. It’s G, C, and D7. Simple. Effective. It’s the "three chords and the truth" philosophy that Harlan Howard famously talked about.

Misconceptions About the Meaning

A lot of people think this is a love song.

It isn't.

Sure, some of the 1950s covers tried to frame it that way—a guy leaving a sweetheart. But if you look at the 1940 Dust Bowl Ballads album, it’s clearly part of a larger narrative about economic ruin. Guthrie wasn't singing to a woman; he was singing to a region of the country that was literally blowing away in the wind.

Another misconception is that it’s a "happy" song.

Because the melody is upbeat and the chorus sounds friendly, it’s often used in upbeat contexts. But the subtext is heavy. It’s the "keep from crying" kind of laughter. It’s gallows humor. Guthrie was a master of that. He knew that if you made a song too depressing, nobody would listen. But if you gave them a tune they could whistle while their farm was being foreclosed on? Then you had a hit.

Impact on Later Artists

You can hear the DNA of this song in almost everything that came after it in the folk and rock world.

💡 You might also like: Kate Moss Family Guy: What Most People Get Wrong About That Cutaway

Bob Dylan basically built his early career on mimicking this specific Guthrie vibe. You can hear it in "A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall." You can hear it in Bruce Springsteen’s The Ghost of Tom Joad.

The idea of the "rambling man" who is forced into the road by circumstances beyond his control started here. The so long it's been good to know you lyrics provided the template for the American protest song.

How to Authentically Perform or Use the Lyrics

If you’re a musician looking to cover this, don’t just sing the Weavers version.

Go back to the Pampa, Texas roots. Understand that the "dust" in the song is a character. It’s the antagonist. To really nail the performance, you have to capture that sense of weary resignation.

- Vary the tempo. Don't keep it a stiff 1-2-3 waltz. Let it breathe.

- Focus on the "Black Sunday" verses. These are the ones that actually tell the story.

- Use a flat-picking style. Guthrie’s "Church Lick" on the guitar is what gives this song its driving, rhythmic feel.

The song is public domain in many forms now, or at least heavily anthologized, so you’ll see it in countless songbooks. But the heart of it remains in that 1935 disaster.

Finding the Best Recording

If you want to hear the definitive version, look for the Dust Bowl Ballads recording.

It’s sparse. It’s just Woody and his guitar. You can hear the grit in his voice. It sounds like he’s actually got dust in his throat. Compare that to the 1951 version by The Weavers. The Weavers version is great—it has beautiful harmonies and a full band—but it loses the "survival" aspect of the original.

Final Practical Takeaways

When you are diving into the so long it's been good to know you lyrics, remember these three things:

- Context is King: The song is a primary source document for the Great Depression. It’s as much a piece of history as a newspaper from 1935.

- The "Good" in "Good to Know You" is Bittersweet: It’s a final farewell to a home that no longer exists.

- Adaptability: The reason it survived is because it can be adapted. It’s been a protest song, a pop song, and a disaster ballad.

To really understand the song, you should listen to it while reading the lyrics side-by-side with a history of the Okie migration. It changes the way you hear the melody. It’s not just a "so long"—it’s a "see you in another life because this one is over."

Check out the Smithsonian Folkways archives for the most accurate lyric sheets. They hold the original Guthrie papers and have the most "unfiltered" versions of his writing. If you're teaching this in a classroom or using it for a project, that's your gold standard.

Stay away from the generic lyric sites that just copy-paste the pop versions. You want the verses about the dust, the church, and the "hard-workin' people." That's where the real soul of the song lives.