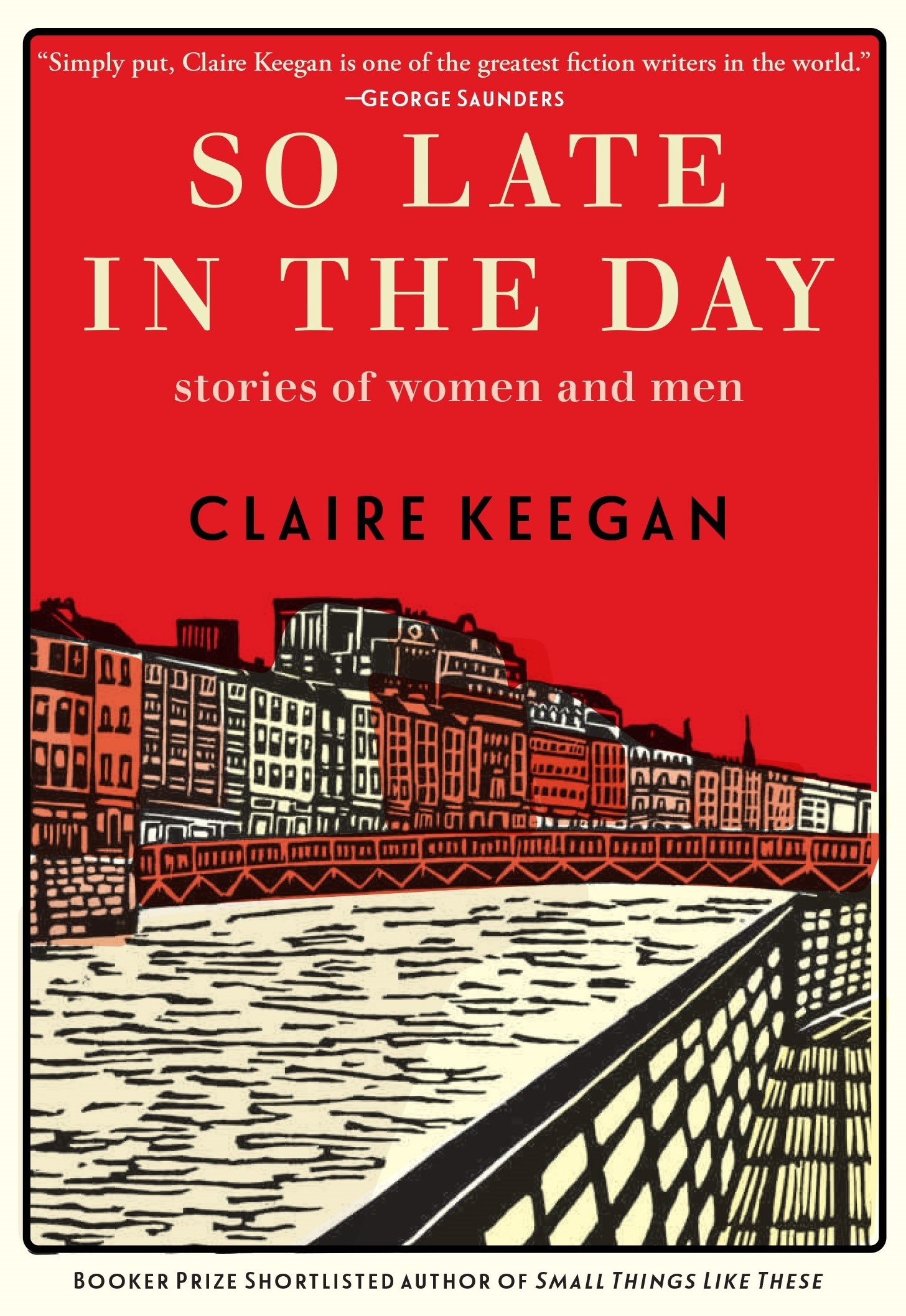

Claire Keegan has this way of making you feel like you’ve just walked into a cold room and realized the heater’s been off for years. It’s quiet. It’s sharp. Her recent work, particularly the collection and the titular story within so late in the day stories of women and men, doesn’t just sit on a shelf. It lingers. You’ve probably seen it sitting on a bookstore table with that deceptively simple cover, but what’s inside is a brutal, precise dissection of why people—specifically men and women—fail to actually connect.

She isn't interested in grand romances. Keegan cares about the silence. She cares about the moments where a relationship could have been saved but wasn't because of a tiny, calcified bit of ego or a long-held resentment that neither party knew how to voice.

The Weight of Small Cruelties

Take the core story, So Late in the Day. It follows Cathal, a man working a desk job in Dublin, who is spending a midsummer Friday counting down the minutes until he can go home. But there’s a vacuum where his plans should be. As the day unfolds, we get these jagged flashes of his relationship with Sabine, a French woman who was supposed to be his wife.

It’s painful. Honestly, it’s hard to read at points because Cathal isn’t a monster in the cinematic sense. He’s just... small. He’s the kind of man who begrudges the price of an engagement ring or gets prickly about how much space a woman takes up in his house. Keegan uses these so late in the day stories of women and men to show that the end of the world doesn't happen with a bang. It happens because someone was too cheap to be kind.

We see this play out in the way he treats a simple request for a gift or his reaction to Sabine’s autonomy. It’s about power. Not the kind of power world leaders have, but the domestic, suffocating power of a man who feels he is owed something just for existing.

Why Ireland Still Haunts These Pages

You can’t talk about Keegan without talking about the Irish context. Even in 2026, the echoes of a very specific, traditionalist past ripple through her prose. While Ireland has modernized at a breakneck pace, the internal lives of her characters often seem trapped in an older, more rigid moral architecture.

In the broader collection of so late in the day stories of women and men, the tension often stems from the Misogyny with a capital M that’s baked into the soil. It’s in the way a priest might speak, or the way a father looks at a daughter. But Keegan is too smart to make it a caricature. She shows how women navigate these spaces with a quiet, terrifying grace. Or, sometimes, how they just leave.

Sabine leaves. That’s not a spoiler; it’s the premise. She realizes that the life offered to her by Cathal is a cage made of "value for money" and stifled emotions.

📖 Related: Alfonso Cuarón: Why the Harry Potter 3 Director Changed the Wizarding World Forever

The Art of Saying Almost Nothing

Keegan’s style is "lean." That’s the word critics love. But let's be real: it's actually "haunting." She doesn't use three adjectives when a noun will do. Most writers try to explain why a character is sad. Keegan just describes the way a man puts a key in a lock, and you realize his entire marriage is over.

- She focuses on the physical object—a ring, a salad, a cold bath.

- The dialogue is sparse. People rarely say what they mean.

- The ending isn't a resolution; it's a realization.

If you’re looking for a happy ending in so late in the day stories of women and men, you’re in the wrong place. But if you want the truth? It’s all over these pages. There’s a specific scene involving a bus ride that perfectly captures the isolation of the modern individual. It’s just a man sitting there, but the weight of his own choices is pressing down on him like physical gravity.

What We Get Wrong About Gender in Fiction

Often, stories about "men and women" fall into tired tropes. The nagging wife. The bumbling husband. Keegan burns those tropes down. She portrays women as people with immense inner lives who are often forced to observe the world from the periphery. The men, conversely, are often portrayed as being trapped by their own inability to be vulnerable.

This isn't "man-hating" literature. It's an autopsy of a culture. When we read these so late in the day stories of women and men, we are looking at the wreckage of the nuclear family model in a world that no longer supports it.

The character of Cathal is actually quite pitiable. He’s a product of a system that told him being "frugal" and "steady" was enough. He was never taught that intimacy requires a kind of emotional reckless abandon. He’s sitting in his beautiful house, and he’s utterly alone because he treated his partner like an invoice to be settled.

The "Late in the Day" Meaning

The title itself is a double entendre. It’s literally a Friday afternoon. But it’s also late in the day for these characters’ lives. It’s late in the day for a certain type of traditional masculinity that can’t survive in a world where women have the agency to simply walk away.

Think about the timing. Midsummer. The longest day of the year. The most light we ever get. And yet, Cathal is in total darkness. That’s the irony Keegan plays with. Even with all the light in the world, if you refuse to look at yourself, you’re never going to see anything.

👉 See also: Why the Cast of Hold Your Breath 2024 Makes This Dust Bowl Horror Actually Work

Real-World Impact and Literary Standing

Since its release, this work has been compared to the likes of Anton Chekhov or Raymond Carver. That’s high praise, but it fits. Like Carver, Keegan finds the "extraordinary in the ordinary." According to data from literary trackers in early 2025, Keegan's works saw a 40% uptick in international sales, proving that these very "Irish" stories have a universal heartbeat. People in New York, Tokyo, and Berlin are reading so late in the day stories of women and men because the feeling of "missing the boat" on a meaningful life is a global anxiety.

It’s also worth noting the brevity. The book is short. You can read it in an hour. But you’ll think about it for a month. That’s a specific skill—the ability to condense a whole lifetime of regret into sixty pages.

How to Approach These Stories

If you’re diving into Keegan’s world for the first time, don’t rush. This isn't a beach read. It’s a "sit in a chair with no phone and a glass of water" read.

- Pay attention to the weather. Keegan uses the environment to signal shifts in the characters' internal temperatures.

- Look for what isn't said. The gaps in conversation are where the real story lives.

- Notice the food. In these stories, sharing food is either an act of love or a tactical maneuver.

The reality is that so late in the day stories of women and men serves as a mirror. You might see a bit of your own selfishness in Cathal. You might see your own desire for escape in Sabine. It’s uncomfortable. It’s supposed to be.

Actionable Takeaways for the Modern Reader

Reading these stories shouldn't just be an intellectual exercise. It offers a pretty stark look at how we communicate today. Here is how to actually apply the "Keegan Lens" to your own life:

Audit your "Small Cruelties"

We all have them. The moments where we choose to be "right" instead of being kind. In the story, Cathal’s insistence on a certain price point or a certain way of doing things eventually erodes the love Sabine has for him. Check your own relationships for these micro-aggressions.

Value the "Unsaid" but don't live there

While Keegan’s characters suffer in silence, use it as a cautionary tale. If you’re feeling the "coldness" that Cathal feels, the solution isn't to retreat into a desk job and count the hours. It’s to speak up before it’s "too late in the day."

✨ Don't miss: Is Steven Weber Leaving Chicago Med? What Really Happened With Dean Archer

Recognize the "Frugality of Spirit"

Being cheap with money is one thing; being cheap with your emotions is another. The most damning part of these stories is the realization that many people are simply unwilling to "spend" themselves on others. Don't be an emotional miser.

Read the collection chronologically

If you have the physical book, start from the beginning. The way the themes of gender and power build across the different stories—including The Long and Painful Death and Antarctica in some editions—creates a cumulative weight that makes the final pages of the title story hit much harder.

This isn't just fiction; it's a map of the pitfalls of being human. Keegan has handed us a guide on what not to do if we want to keep the people we love. Whether you're a man trying to understand the quiet frustrations of the women in your life, or a woman looking for validation of those "gut feelings" you can't quite name, this book is essential.

Stop looking for the "big" moments. Start looking at the way you spend your Friday afternoons. That’s where your life is actually happening.

Next Steps

To truly understand the depth of these themes, compare this work to Keegan’s Foster or Small Things Like These. You’ll notice a recurring thread: the vulnerability of children and women in a society that prioritizes "order" over "empathy." After finishing the book, take a moment to write down the one "small thing" you’ve been withholding from someone you care about. Then, go give it to them. Don’t wait until it's late in the day.