If you Google single cell protein images, you’re probably expecting to see something that looks like a steak or maybe a block of tofu. Honestly? You’re going to be disappointed. Most of these images look like beige sand, muddy water, or a petri dish that someone forgot in the back of a fridge for three weeks.

It’s weird.

We’re told this stuff—Single Cell Protein or SCP—is the future of how we feed eight billion people without destroying the planet, yet the visual reality is basically "high-tech sludge." But if you look closer at the microscopy or the industrial bioreactors, there’s actually a lot of incredible science hidden in those boring-looking photos.

What You’re Actually Seeing in Single Cell Protein Images

When you look at a photo of SCP, you aren't looking at "meat." You’re looking at a massive colony of microorganisms. Specifically, we’re talking about algae, fungi, yeast, or bacteria.

Microbes.

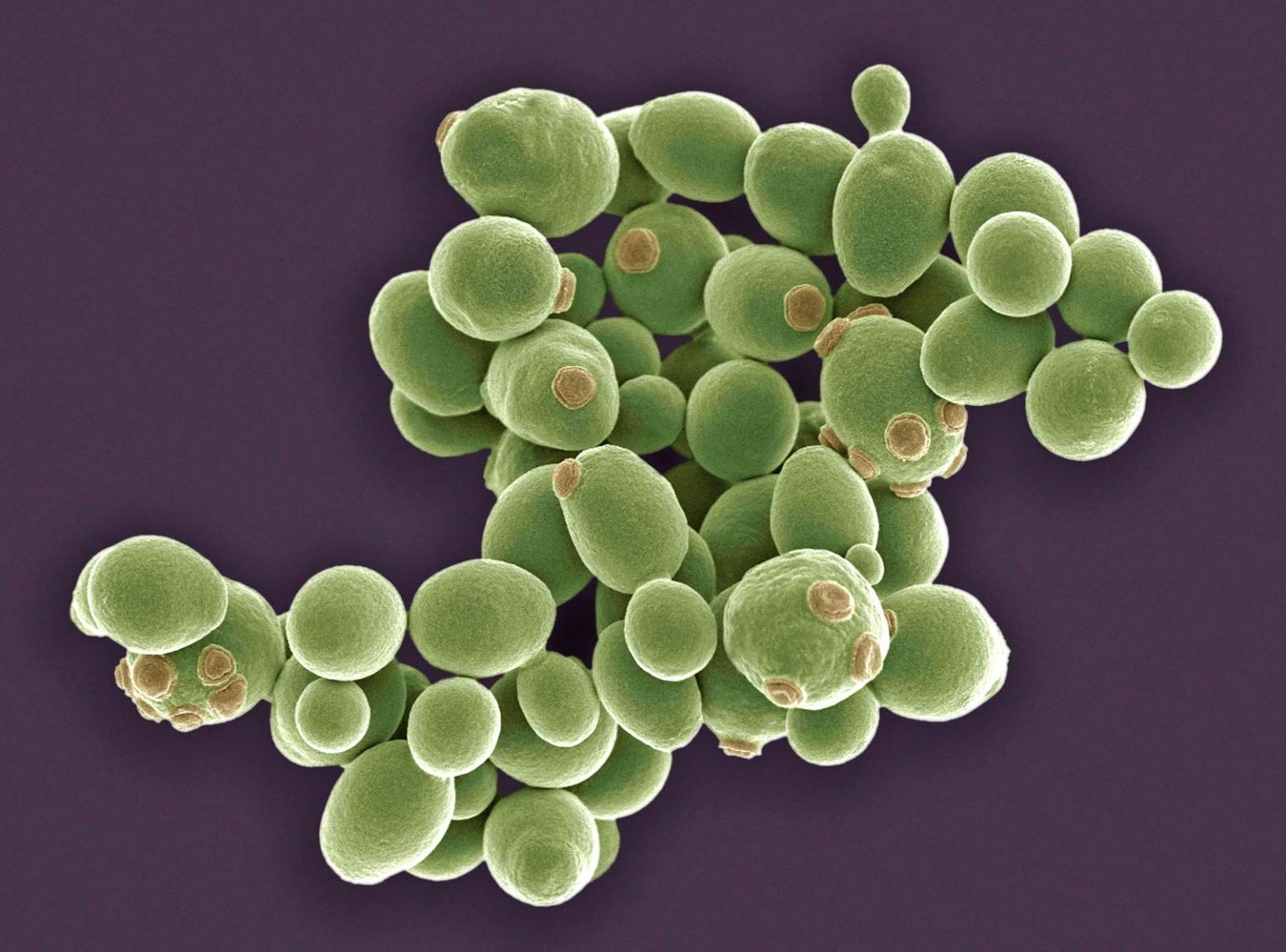

The images usually fall into two camps. First, there’s the "macro" view. This is the dried powder. It’s often a pale yellow or a dull green if it’s spirulina-based. It looks like protein powder because, well, that’s essentially what it is. Then you have the "micro" view. These are the single cell protein images captured via Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM). This is where things get cool. You see these perfect, geometric spheres of Chlorella or the long, branching filaments of Fusarium venenatum.

That last one is important. Fusarium venenatum is the fungus used to make Quorn. If you’ve ever eaten a Quorn nugget, you’ve eaten a processed version of those microscopic threads.

Why the "Sludge" Look Matters

The liquid state you see in many lab photos is actually a fermentation broth. It’s a highly controlled soup. Scientists like those at KnipBio or Deep Branch spend millions of dollars making sure that "muddy" water has the exact right balance of oxygen, nitrogen, and carbon. If the image looks cloudy, that’s a good sign. It means the microbial density is high.

High density equals more protein.

✨ Don't miss: Steven Test Personal Website Steven Test Account \#1: What Is Actually Going On?

The Disconnect Between Lab Photos and Marketing

There is a massive gap between what a scientist sees on a slide and what a startup shows investors. If you look at promotional single cell protein images from companies like Solar Foods, you’ll see "Solein." They often show it as a bright yellow flour or integrated into a sleek-looking pasta dish.

They’re trying to bridge the "ick" factor.

Most people don't want to think about eating "hydrogen-oxidizing bacteria." They want to think about sustainable nutrition. But the raw images from the production floor tell a different story. They show stainless steel vats, tangled hoses, and digital readouts. It looks more like a brewery or a pharmaceutical plant than a farm.

And that’s the point.

Traditional farming takes up about 40% of the ice-free land on Earth. SCP production takes up almost nothing by comparison. You can grow it in a skyscraper in the middle of Tokyo or a shipping container in the Sahara. When you look at an image of a bioreactor, you're looking at a 1,000x increase in land-use efficiency.

Breaking Down the Types of SCP You’ll See

Not all microbes are created equal. The images vary wildly depending on the "feedstock"—which is just a fancy word for what the microbes eat.

- Bacterial SCP: These images often show Methylophilus methylotrophus. It’s tiny. It’s efficient. It usually looks like a fine, white dust in its final form.

- Yeast SCP: Think Candida utilis. These cells are bigger and rounder. They’ve been used in animal feed for decades. In photos, yeast-based SCP often has a slightly "toasty" or tan color.

- Fungal SCP (Mycoprotein): These are the most "structural" images. Because fungi grow in hyphae (long strings), the resulting protein has a natural texture. This is why it’s easier to turn fungi into a "chicken" breast than it is to do the same with bacteria.

- Algal SCP: Bright greens and deep blues. Spirulina is the poster child here. Under a microscope, it looks like tiny spirals.

The Problem With "Fake" Science Graphics

If you spend enough time looking for single cell protein images, you’ll run into those overly polished, 3D-rendered graphics of "blue cells" floating in space.

Ignore them.

They’re basically useless for understanding the tech. Real science photography in this field is messy. It’s black and white SEM shots or grainy photos of a centrifuge. Real experts, like those contributing to the Journal of Cleaner Production, focus on the biomass yield shown in those unglamorous photos. They’re looking for "flocculation"—where the cells clump together—which makes it easier to harvest the protein from the water.

The Role of CO2 and Gas Fermentation

One of the most mind-bending parts of this industry involves turning air into food. Companies like LanzaTech use gas fermentation. They capture carbon emissions from steel mills and feed them to bacteria.

✨ Don't miss: Why Pictures of the Sun in Space Look Nothing Like What You Expect

The images from these facilities are wild.

You see giant pipes connected to industrial chimneys, leading directly into fermentation tanks. It’s literally turning pollution into protein. When you see a photo of a clear liquid turning opaque in a LanzaTech lab, you’re watching carbon atoms being rearranged into amino acids. It’s basically alchemy, but with more sensors and fewer robes.

Why We Don't See This in Supermarkets (Yet)

You might wonder why, if we have all these photos of successful protein production, you can't buy "Bacteria Burgers" at the local shop.

Regulations.

The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and the FDA in the US are incredibly strict about "Novel Foods." Every one of those microbes seen in single cell protein images has to be proven safe, non-toxic, and non-allergenic. It took Quorn years to get through this process. Now, companies like Air Protein are going through the same gauntlet.

There's also the cost.

Growing microbes is cheap in a lab but expensive at scale. The electricity needed to keep those bioreactors at the perfect temperature is a huge hurdle. However, as renewable energy prices drop, the "math" of these images starts to make more sense.

A Look at the Environmental Impact Data

A 2022 study published in Nature suggested that replacing just 20% of global beef consumption with microbial protein could halve deforestation by 2050.

Think about that.

When you look at a boring photo of a green algal pond or a gray bacterial vat, you’re looking at the potential salvation of the Amazon rainforest. It’s a heavy burden for a beige powder to carry, but the data is solid. SCP uses roughly 1/10th of the water of traditional soy production and produces a fraction of the greenhouse gases.

How to Spot "Real" Quality in SCP Images

If you’re a researcher or just a curious nerd, there are things to look for in these photos to tell if the production is actually good:

💡 You might also like: Arlo and Google Home: What Most People Get Wrong

- Consistency: The powder should be uniform. Blotches or color shifts usually mean contamination or uneven drying.

- Cell Integrity: In microscopic images, the cell walls should be intact. If they look "shriveled," the drying process was too harsh, which can denature the proteins.

- Clarity of the Supernatant: In a fermentation photo, the liquid around the cells should be relatively clear once the "crash" (settling) happens.

Actionable Steps for Exploring SCP Further

If you’re interested in moving beyond just looking at photos and actually getting involved or investing in this space, here’s how to do it without getting lost in the hype.

Check the "Feedstock" first. Not all SCP is "green." If a company is growing microbes on sugar (glucose), they are still tied to traditional agriculture. Look for companies using "second-generation" feedstocks—things like wood chips, agricultural waste, or captured CO2. That’s where the real environmental revolution is happening.

Follow the "Microbial Protein" tag on LinkedIn. Sounds boring, right? It isn't. This is where the actual engineers at companies like The Protein Brewery or Solar Foods post raw, unedited photos of their pilot plants. It’s far more informative than the "stock photo" versions you’ll find on news sites.

Read the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA). Any SCP company worth its salt will have a published LCA. This document explains the "cradle-to-grave" impact of their protein. Don't trust a pretty image of a green leaf next to a bioreactor; trust the carbon-equivalent-per-kilo stats in the LCA.

Look into "Precision Fermentation." This is a subset of SCP where microbes are "programmed" to produce specific proteins, like whey or collagen, without the cow. The images here look very similar to standard SCP, but the end product is a bio-identical match to animal protein. It’s the next level of the "food from thin air" story.

The next time you see single cell protein images that look like a boring science experiment, remember that you’re looking at the blueprint for a world where we don't have to choose between eating meat and having a planet. It might just be the most important beige powder in human history.

Next Steps for Implementation:

- Verify the Microbe: If you are sourcing SCP for animal feed or human consumption, request the specific strain name (e.g., Pichia pastoris) and a COA (Certificate of Analysis) to ensure purity.

- Compare Protein Density: Don't just look at the volume of the biomass. Check the "crude protein" percentage on the dry matter basis. High-quality SCP should be between 60% and 80% protein.

- Monitor Scalability: If you are an investor, look for images of "Demo Scale" plants (10,000+ liters). Small lab flasks are easy; 50,000-liter continuous fermentation is where most companies fail.